When journalist David Dobbs’ mother was dying, she shocked her children by asking that her ashes be spread in the waters off the coast of Hawaii, so that she could be with her former lover, “Angus,” who had been shot down over the Pacific in the last days of World War II. This unexpected request, and his brother’s fulfillment of their mother’s wishes, launched Dobbs on a quest to find out who his mother’s lover had been and why she had carried his memory for so long. My Mother’s Lover appeared at The Atavist on June 7, 2011.

Here, Dobbs tells TON the story behind the story. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Why did you decide to write this story?

In February of 2002, a few months after my mom died, my brother Allen put my mom in the sea, and he took a few pictures of the scene. A few days later, he sent them along in an e-mail describing the little ceremony he had fashioned for her. That reinvigorated my puzzlement about who this Angus was and why my mom wanted to go back to him. It was while reading that email that I essentially decided, emotionally anyway, to write this story. It just brought everything up. There was too the tension between the scene he described and the deep, dark Vermont winter I was in, and as she floated down onto coral there in Hawaii, it seemed to connect in a weird way to the book I’d just finished, which was about the origin of the Pacific coral reefs.

How did you begin your search?

I started by calling my mother’s cousin, Betty Lou, who grew up with her and stayed close all my mother’s life. She’s still in Wichita Falls, Texas. She remembered that this fellow was a flight surgeon in the Air Force, something I already knew, and she believed he had been divorced before he met my mom. She also remembered that his real name was Norman, that his last name started with a Z, and that he was from Iowa. With that information I started to try to find who he was and how he became connected to my mom. I found that out and also a lot of things about my Mom that I hadn’t known: that she was a very different person in her youth than she was later, and that her brief and extremely intense relationship with this fellow, Angus, was a huge turning point in her life. Their affair had immense reverberations in two different families.

How did you find Angus’s family?

It was quite extraordinary. When I hung up with Betty Lou, I had essentially a Norman Z. from Iowa who was a flight surgeon in World War II. That proved enough. I went online and found that the record of the World War II dead—it’s called the World War II Honor List of Dead and Missing—for each of the fifty states. All I had to do was scroll down, county by county, and in Johnson County, Iowa, the very last entry is Norman E. Zahrt, with his serial number; and his rank of captain, which is consistent with him being a flight surgeon. And the real gold: the date that he went MIA was July 25th, 1945, which matched Betty Lou’s memory that my mother learned of his death after the war ended in August.

So that all gave me confidence that this was the Norman I was looking for. I started searching genealogy sites, and when I found a Zahrt in Iowa, I would send an email saying that I’m looking for a Captain Norman E. Zahrt, who died on July 25th, 1945 and saying that he was a friend of my mother’s during the war. I either didn’t get a response to these emails or I’d get one saying, “No, don’t know any Norman, doesn’t ring a bell.”

And then I get one that begins:

“David,

What a surprise to get an email from you. Yes, my father is Norman Zahrt. My mother is Luella. Norman and Luella had two children: David born Sep 37 and Christy born Jan 40. I don’t have words to describe the mixed emotions that come to me when I revisit this issue. I’ve come to learn that in the process of growing up, one accumulates scars and that the challenge is learning to own your scars and live them.”

In that letter from Norman’s son, David, he sends you a numbered list of 19 questions.

Yes, it’s this weird mix of prosecutorial and compassionate, cooperative tone. He’s obviously very smart, and very surprised, and intensely curious, and maybe a little bit piqued. You can read this in his questions. Like “What prompted this search? What is your mother’s name? What was her occupation? Did your father know she was with my Dad?” And he signs it along with his sister, Christy.

Reading it, it seemed clear that my mother may have broken up his parents’ marriage—and that my response could make the difference between working with him and never hearing from him again. I dithered for several days. Then I just decided to trust his statement that he felt one should own one’s scars, and I just wrote back answering his 19 questions as fully and frankly as I could. He and Christy received this graciously, and from there we worked together to try to excavate their story.

I had to construct two family histories. Constructing my half was a matter of talking to my siblings, to Betty Lou, to my father, and to some of my mom’s oldest friends. The Zahrts meanwhile were doing the same thing, talking with members of their family. They had this huge mystery to fill in about their dad’s life, too.

What aspect of the reporting was most difficult?

What was most resistant to reconstructing, not surprisingly, was the time my mom and Angus spent together. There was almost no paper trail. I found one person who knew Angus in Hawaii—a squadron mate. But he was reluctant to talk about the private life of someone he knew in a time of war, who revealed things to him that you probably wouldn’t in any other scenario. So I didn’t have much to go on, which is why the photos that my mom had kept were so valuable.

Editors’ note: In this audio slideshow, David Dobbs talks more about how he used those photos to try to understand what might have happened between his mother and Angus:

How did you end up selling the story to The Atavist?

This story was on and off my stove top for years. I wrote it up as a book proposal back in 2005 but decided not to shop it around because I hadn’t figured out how to approach the story yet. At one point I wrote it up as a 7,000-word memoir and sent it to The New Yorker, who nibbled on it but didn’t take it. It was a pretty good piece at that point, but I still hadn’t quite figured out how to write about it so that the voice and structure were in sync. Then, about a year and a half ago when I was shopping for an agent, I wrote up a 4,000-word book proposal for it; it was one of four books I was considering then I ended up instead deciding to write The Orchid and the Dandelion, which I’m working on right now.

Meanwhile I also pitched the story to Wired, as a story mainly about this unit in the U.S. Army called the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command—they go out and find bodies of missing soldiers—with this search for Norman as flavoring. Nick Thompson, who’s now a senior editor at The New Yorker, was my editor at Wired, and he learned of the story then. When Wired turned it down, Nick told me he was working with a friend on creating a new kind of publication that this might be right for, and to remind him of this story when they got that thing together. When The Atavist came out in January of this year, I sent him a note and asked whether this would be the time to pitch this story. He said definitely. A week later Evan Ratliff, the editor at The Atavist, and I talked for about 90 minutes, and Evan said, “Let’s do it.”

What were the most challenging parts of the writing process?

The hardest part was figuring out which, of the many stories within this saga, I should use as the main thread. Looking back, I can see that all through the years I messed with this story, I was struggling with this question. This saga contained, at minimum, a mystery; a manhunt; a love story; a family history; a detective story; and a story of a son reckoning with his mother’s hidden life. I see now that I had to find, among all those options, the one that would best carry implicitly the others—because it was death to try to do two of them in full. But it took me a while to realize that, because I’m stupid and I’m greedy and wanted to tell them all.

What brought me up was sending what I thought was a finished version of the piece—15,000 words, which I’d slaved on for weeks—to Steve Silberman and Adam Rogers and Maryn McKenna. To my horror and benefit, they actually did what you’re supposed do in such instances, which is be brutally frank. Steve sent back a sharp-eyed, granular edit that smoothed about a hundred rough seams and stumblers. (His best comment began, “Oh God, no!”) Adam and Maryn attacked the structure. For this I owe them—well, you’ll see.

Adam called me and said, “I don’t know memoirs that well, but I know mysteries. You’re trying to do both. And you’re fucking them both up.” He was right. He pointed out that if I set a story up as a mystery up front, then the reader, his mystery hunger aroused, will feel cheated if that mystery doesn’t prove central. And I had done that: There was a genuine mystery, early on in both my mother’s life and in my own investigation, as to whether my mother’s lover had actually died or just snuck home after the war. My mother’s cousin, Betty Lou, had wondered about this for 60 years. This raised the question of whether my mother might have wondered about it all that time too—a pretty intriguing possibility.

So near the opening of that early version I had one short paragraph quoting Betty Lou, raising that question. As it happened, I solved that particular mystery fairly soon in my investigation, and undramatically, so it was valuable mainly for how alarmingly stimulative it was when I first encountered it. It wasn’t central to the story. Yet as Adam pointed out, the mystery genre’s cues are so powerful they gave this briefly raised mystery a Pavlovian power, one that demands that it be central to the story. Absent that, I had sold the reader a mystery—and then taken it away.

So Adam, a mystery nut, says, “Dump the mystery.” I think, “What an ass!” About an hour later I get Maryn McKenna’s email saying, “I know you don’t want to hear this right now, but you don’t have the right structure.” Great! And when I dig into what she’s saying I realize that they’re both right: the mystery cue has warped everything up front so bad, the structure didn’t work—it couldn’t, because the story was trying to be two things at once. You can’t do both The Maltese Falcon and Gone with the Wind.

So I dumped The Maltese Falcon. Then all I had to do was figure out how to structure Gone with the Wind.

How did you arrive at the structure you settled on?

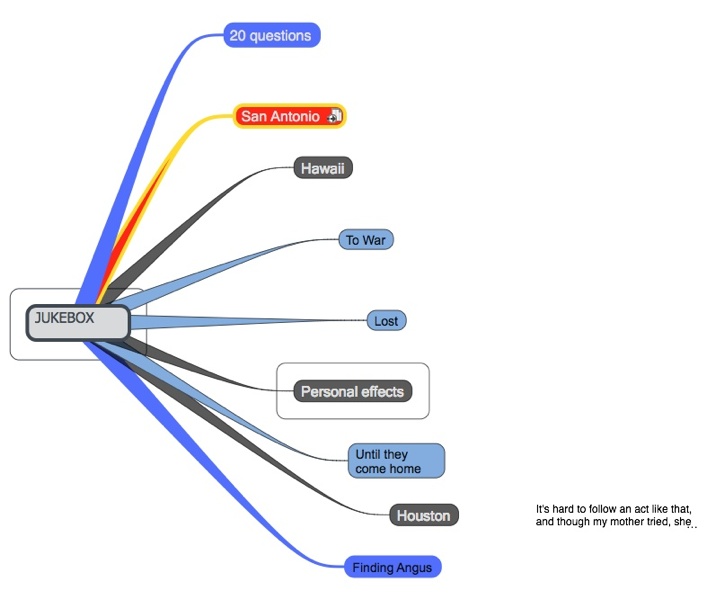

I identified the main narrative chunks of the story and I played with those pieces, about a dozen or so, in about 8 or 10 different arrangements. Eventually I used a so-called mind map, using this Mac program called NovaMind, so I could move around little blobs with section titles on them instead of manipulating an outline. That helped partly because it kept me from messing with the words and filling in details, which I almost always end up doing if I play with an outline. It forced me to work in just structure.

Eventually I settled on a fairly conventional, more or less chronological string, except that the story opens with the ending, as it were, with my mother’s burial and, flashing back just a bit, with her request that she be buried in the water off Hawaii. That was organic to the actual story’s structure, however, because her request was the initial spark that got me digging this whole story up. If there were no weird request, the story of her love affair would have stayed buried. But after that first chapter I jumped back to her childhood and just told the story through time. I didn’t have to mess with it much after that.

My work through all that time was made easier by two things I read while working on this story. Both were interviews in The Paris Review—one with John McPhee and one with Janet Malcolm. McPhee reminded me that if you get the right structure, transitions and many other small things get easier. He’s right. And Malcolm reminded me that a writer’s biggest problem is what to leave out. That drove several excruciating but good decisions as I went from my 15,000-word version down to the final 12,000 or so. Cutting the early mystery was such a case—incredible material, but it was weakening the piece. I left some other darlings behind as well.

As personal as this story is, you maintain a certain psychological distance from it. How did you decide what distance and tone to take?

The more I worked on the story, the more I moved back. This was a huge, key thing, removing myself to make it less and less a story of a son considering a history’s impact on himself. It’s the natural thing for a writer to want to put in there, I think, but I don’t that’s where the most interesting story is. I wanted to downplay that, to have it in a limited form, but in the most powerful place and in the most powerful form possible, because in a sense, it’s the most powerful part of the whole thing.

It seems like by creating that psychological distance, you give your readers the opportunity to put themselves in that situation.

Yes, they have to fill in the space. I try to take a lot of cues from music when I’m thinking about how to structure a piece and what to put in. I play the violin—not terribly well—and when I was writing this piece, I kept thinking of a Schubert quartet that I used to play that’s very beautiful and intensely emotional. There’s this line that he develops during the first movement, and the second violin has this gentle, running theme that is one of the most beautiful things you’ve ever heard. It’s just aching. Then the first violin brings in this beautiful singing line, and the climax is just so gorgeous that when you play it, you almost can’t contain yourself. It’s quite sexual. You can feel this thing coming and you can’t wait but you don’t want it over. Then it arrives and it’s utterly fulfilling; playing it, you want to weep and sing at the same time, but it’s energizing too, so you want to do it again. The phrase is so perfect it just begs to be repeated. But Schubert doesn’t let you. Any other composer would have repeated that line, or elaborated on it. Schubert plays it once, you almost can’t stand it—and then he pulls the music back and returns to the piece’s excruciatingly beautiful but understated opening theme, only now it has a whole body of new tension built into it.

And that’s how I tried to place this one little part of my story, where I talk about what it was like to be my mother’s son. I don’t think that would be a proper part of the story—to bring me in as a boy—unless it reflected upon who she was. Yet the picture of my mom, of Evelyn Jane Hawkins Preston Dobbs, would be incomplete if you didn’t understand how much love she delivered to those that were close to her. That’s where the son’s experience comes in as relevant. And I decided to put it just short of the story’s end—and then cut it off and go into something else. So it’s very short. But it’s the most powerful stuff that I could distill from that passage.

What was the editing process like?

That went really well; very smooth and productive. The mind-blowing thing was how fast it happened once I turned the story in. I sent it to Evan at The Atavist, who gave it a really good read and sent it back with suggestions of two sorts: a bunch of little tweaks throughout which very much sharpened the story—stuff from paragraph-level to maybe intra-sentence changes; and two or three sections—mostly background stuff, early histories from my mom and Norman—where he thought we needed to lose between 30 and 50 percent, to better emphasize the main thread.

Was there anything about writing for an e-book publisher that was different from your experience with traditional print publishers?

It was similar in some ways to doing the long-form kind of stories that I usually do for print publications like The Atlantic and the Times Magazine — really good, smart editors helping you work up a story idea. That part felt familiar. But new, of course, was the opportunity to load it up, in the iPad version, with anything you wanted to in terms of multimedia. There’s little technical limitation to what you can throw in there.

Screenshots below are from the iPad version of “My Mother’s Lover.” A clip of Dobbs’s narration is here. (Audio and images courtesy of The Atavist and David Dobbs.)

Anticipating that was neat, and executing it once I had the story done was great fun. But when I was writing I did not think about that stuff, both because I’m a word person, and I just kind of disappear and I forget that pictures exist, and because I knew I was writing not just for the iPad, but also for the Kindle version, which would just have a few photos in it.

Whose idea was it to include the World War II film showing a rescue squadron rescuing a pilot?

That was Evan Ratliff, the editor, and Jefferson Rabb, the creative director. They have this tool to put these things together, and they just went digging online while I was agonizing over words. They found this silent film at this historical film archive called Critical Past, and separately, they found a voiceover that happens to be by a squadron mate of Angus’s. The audio describes what it was like in his unit—and a sword attack that killed 30 to 40 people in the barracks next door to theirs. I thought it came off really well; it makes the dangers that Angus is facing at that point in the story more immediate.

Did The Atavist pay you a set fee, or was your payment based on how many people buy the story?

It’s a hybrid. There’s a flat, four-figure fee when it’s accepted, and then you get roughly half the net that The Atavist receives from every e-book sale, which is 70 percent of the cover price.

I know your calculus on this story may not have been primarily financial, but from a monetary point of view, do you think this story was worth it?

It’s still selling, so I don’t know what it’s going to make all in all. But it’s a comfortable compensation because it really took off right away. It went to number one among Kindle Singles within 24 hours, and for a week or two it was in the top 20 of all Kindle books. If it had gone out and only two or three hundred people had bought it, it would have been kind of a low return money-wise on the investment compared to other stories I write—but as you say, it’s a different sort of story that I really wanted to write anyway.

Economically, to me this model seems quite viable. It’s an exciting new way for writers to get work out, particularly of a certain length. This story was about 12,000, and it simply wasn’t going to work at five or six thousand words.

The way your story ends seems perfectly adapted to the e-book format. Without spoiling the ending for those who haven’t read it yet, can you talk about how you did that?

As I said earlier, I didn’t think, when I was writing the story, about what would go on with the multimedia. But that changed with the ending. I wanted to get the ending tonally right, and I couldn’t come up with a satisfactory last sentence. I must have tried a hundred. There’s always a temptation, especially with a big reverberant story like this, to use the last sentence to sum it up, or comment on it, or add something—to ring the bell, maybe a little too hard.

Evan had a very sensible suggestion, which I’m going to put on my wall. He said, “If I’m not quite sure of what else to do, I just try to end with the last action.” I thought, “That is a great idea, but I don’t have the right final action.” There was one, but it wasn’t enough. And then I realized, I could change that. I could create the last action. I got two photos that had been on my hard drive that had never been printed, printed them out in the same 2 ¼” size as the photos in my mom’s photo album—a set of pictures that drove the story in some places—and placed them in the photo album next to each other. And that became the last action in the story. It was this wonderful weird thing: The immediacy of the process, the fact that I could think of that and actually make it happen because the production cycle was so fluid, let me finish the story by finishing the story.

A glimpse behind the scenes: