Two-thirds of science journalism students and 61 percent of National Association for Science Writing (NASW) members are women. Yet men have more jobs in newspaper newsrooms, more bylines in the top 10 newspapers, and, as last year’s Science Byline Counting Project found, more feature bylines in the most prestigious print magazines.

Men are also more likely than women to win prestigious awards in science writing. I tallied the winners of the prestigious AAAS / Kavli Science Journalism Awards from 2007 to 2016 and found that men won 60 percent of those awards. In the past decade, 63 percent of first-place winners of the Society of Environmental Journalists’ Award for Reporting on the Environment have been men. Since the inception of the American Geophysical Union’s Walter Sullivan Award for Excellence in Science Journalism in 1989, three-quarters of those awards have gone to men. (The National Association of Science Writers’ awards come closest to gender parity, though even they don’t reflect the female skew in science writing: Between 2007 and 2016, the NASW Science in Society Awards have been split evenly between men and women.)

Discussions about the causes of and potential solutions for these gender disparities abound at conferences, happy hours, and online writers’ groups. In those discussions, one issue often emerges: gender differences in pitching habits.

Some editors say that in their experience, women are less likely to pitch a story after an initial rejection, whereas men get right back on the horse. “One pattern I’m seeing is that men pitch more persistently and optimistically,” says Laura Helmuth, health and science editor at The Washington Post. “In response to rejection, men will come back immediately with another story idea, unapologetically.”

Jamie Shreeve, deputy editor-in-chief at National Geographic, also says men tend to pitch him more aggressively. Men are more likely to pitch him again, even if their previous work together did not go smoothly. “If I assign a story to a writer and it turns out to be a difficult project—because the rough draft isn’t good, or it takes me a lot of work to get it where I want it to go—it should be pretty obvious to the writer that this piece wasn’t an easy thing to get into shape,” he says. “But when the writer is male, he comes right back and pitches me [again]. I can’t think of a time a female writer has done that.”

Women writers’ narratives about pitching often include feelings of self-doubt. At a 2012 event called “Throw like a Girl: Pitching the Hell out of Your Stories,” Amy O’Leary, then a New York Times reporter, said she noticed she pitched differently from her male colleagues, who would whip up a pitch after reading just a snippet on a topic, while she put painstaking time and effort into each pitch. “Early on, I lacked the confidence to pitch as much as I wanted,” she said.

With that in mind, editors and experienced writers often encourage women, especially young ones, to be more confident and assertive when pitching. Just lean in, à la Sheryl Sandberg. “Submit like a man,” urges Kelli Russell Agodon, a former editor for the literary journal Crab Creek Review, in an essay at Medium. By that, she means: Send out more ideas immediately after you’ve been rejected.

Persistence and confidence are good traits for any journalist to cultivate, but do men and women actually pitch differently? And if yes, how so? To identify similarities and differences in men’s and women’s typical pitching behaviors, we surveyed 224 science, environmental, and health writers. About three-quarters of respondents identified as female. (See below for more details about our methods and sample and to access our raw data.)

Our results show that men and women in many ways pitch similarly—but when men push back against a rejection, they are more likely than women to do so by proposing an alternative angle. Our data also suggest that pushing back after a pitch has been rejected may yield different results for men versus women. These results offer a starting point for a deeper discussion of the relationships among gender, pitching habits, and participation and achievement in science journalism.

Women Pitch as Much—and as Hard—as Men

Is the disparity between women’s and men’s bylines in prestigious feature wells explained by women pitching fewer stories than men, laboring for longer over each pitch, failing to follow up when editors don’t respond to pitches, or dropping ideas after they’ve been rejected by one publication?

According to our survey, no—on all counts. Our survey found no discernible gender differences in these aspects of pitching behavior. The typical respondent in our survey, regardless of gender, files one to three pitches a month, spending no more than three hours on news pitches and four to eight hours on feature pitches. And writers in our survey typically nudge unresponsive editors after a week or two and give up on an idea after two or three rejections.

Women Cold-Approach Editors More Readily Than Men Do

Contrary to some anecdotal reports, our results suggest that on average, women may in some respects be more persistent or proactive than men in their pitching strategies, especially when it comes to approaching editors they haven’t met. Compared with male writers, female writers were slightly more likely than male writers (65 percent of women and 54 percent of men) to report that cold-pitching new editors is part of their overall pitch strategy. However, this difference was not statistically significant3 and may not be meaningful.

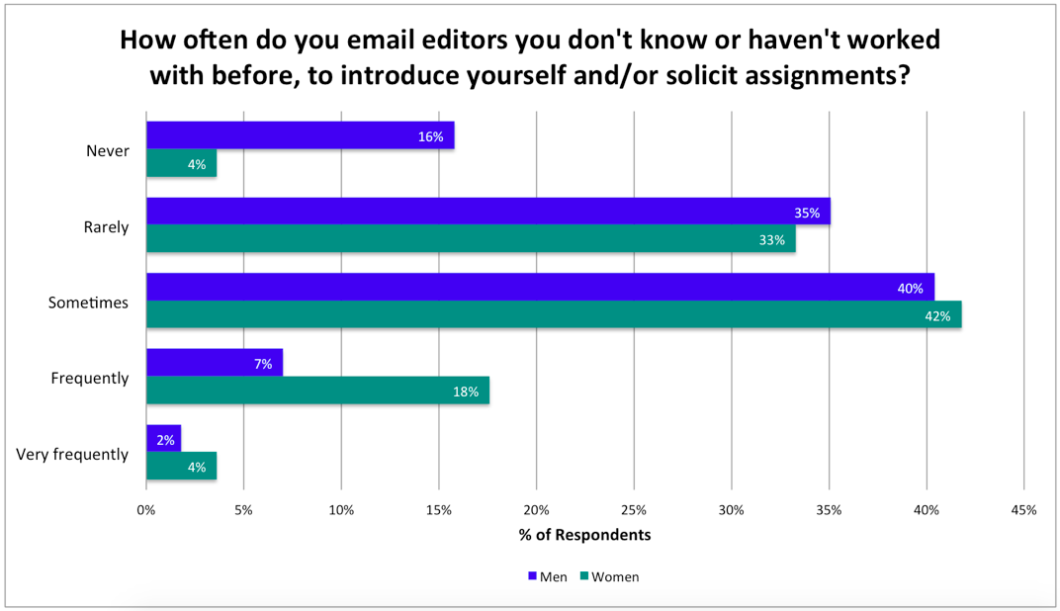

Women were, however, significantly more likely than men to email new editors to introduce themselves or to solicit assignments4. Twenty-two percent of women reported that they do this frequently or very frequently, compared with 9 percent of men. In fact, there were relatively few women who hadn’t tried this strategy—only about 4 percent, compared with 16 percent of men.

Men and Women Attempt Pushing Back on Rejections at Similar Rates …

We also asked how writers typically respond when a pitch is rejected. Among both men and women, most people said they typically either thank the editor and move on (37 percent of women, 38 percent of men) or later pitch the same editor a different story (53 percent of women, 41 percent of men). Notwithstanding anecdotal reports that men tend to be more aggressive than women about pushing back on rejected pitches, neither group reports regularly doing so (4 percent of women, 9 percent of men).

Sixty-one percent of men and 50 percent of women said they had ever pushed back on a rejection, trying to sell the same idea or a variation on it to the same editor who initially rejected their pitch. (The gender difference was not statistically significant5.)

… But Men and Women Use Different Strategies

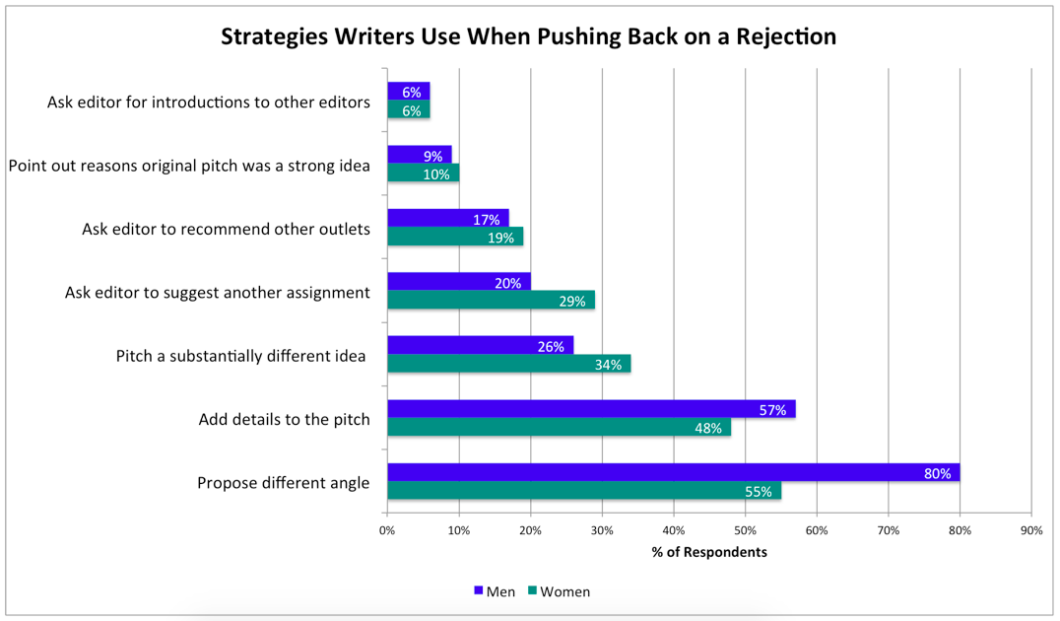

Pushing back after a rejection can take many forms. A writer might provide an editor with additional information, suggest new angles on the original idea, pivot to discuss an entirely different story idea—or put the onus on the editor to suggest a viable assignment. Helmuth says the only time such persistence sways her is “if the writer says, ‘Oh, sorry—I didn’t explain the best part! There’s a different angle here.’”

Every once in a while, she says, “I get a man who’s like, ‘No, you’re wrong.’ They’ll argue with me about a story rejection, or question my judgment on why I turned it down. When there’s a writer who feels entitled or personally insulted, it’s most commonly a man.” Unsurprisingly, she says she’s unlikely to choose to work with writers who try this tactic.

In our sample, respondents’ most common strategies for persisting with the same editor after a pitch is rejected were to propose a different angle and to add compelling details. We did observe a significant gender difference in one specific strategy for pushing back on rejected pitches. Eighty percent of men who said they’ve ever pushed back on a rejection (N = 28) have tried suggesting a different angle, compared with just 55 percent of women who said they’ve done so (N = 51), a significant difference6. (There were no significant gender differences in other strategies.)

Pushing Back Works Better for Men than for Women

Our data also suggest that when men push back against rejections, they may be more successful at winning an assignment than women are. Among women who reported doing so, the majority (58 percent) said that appealing an editor’s decision has never or rarely resulted in an assignment for them, whereas the other 42 percent said that it sometimes, frequently, or almost always does. Men who persisted in pursuing rejected stories with the same editor, though, showed the opposite pattern. The majority (61 percent) said that pushing back sometimes, frequently, or almost always results in an assignment, whereas the other 39 percent of men said it never or rarely does. This pattern was marginally statistically significant7.

The Role of Implicit Bias in Assigning

It’s tempting to recommend that women should push back more or differently on rejections, but that alone is unlikely to eliminate gender disparities in science bylines or other markers of achievement in science journalism. Even if more assertive or more savvy repitching does sometimes get men a juicy assignment—the kind that get included in anthologies and rake in awards—there’s no guarantee that women would achieve the same level of success if they more often used the same strategy.

As decades of research have shown, assertive behavior can have different consequences for men and women. Studies have found that women are more likely to be judged and penalized harshly for assertive behavior than men. To manage social judgments, women often preempt negative judgments by asking for less, softening language, or making apologies.

Editors may also—consciously or unconsciously—judge pitches differently depending on whether they’re coming from women or men. Novelist Catherine Nichols, frustrated by a string of rejections, began submitting her novel to agents using the name George instead. As “Catherine,” Nichols’s reply rate was roughly 1 in 25; as “George,” it was closer to one in three. “[George] is eight and a half times better than me at writing the same book,” she wrote in a 2015 essay at Jezebel. In reflecting on why “George” may have seen more success, Nichols writes that when she met face-to-face with one agent, he said the first 20 pages of her novel were “so ambitious he doubted that I would be able to pull off the whole book at that level.” Perhaps, she says, gender shapes agents’ ideas of a writer’s capabilities. “The difference could be in the gut assessment of how likely a George is to pull off something ambitious,” she writes. “To some degree, I was being conditioned like a lab animal against ambition.”

Helmuth says she’s had women write her saying, “Sorry for pitching again, but …” Statements like this are often interpreted by editors as betraying a lack of confidence on the part of the writer. That may sometimes be the case—but it’s also possible that women have been socialized to express themselves in a more deferential way because to do otherwise is to ensure rejection.

“There’s a fairly solid body of research that supports that men are judged on potential and women are judged on experience,” says Lauren Morello, U.S. news editor at Nature. “It’s something that rings true to me—I’ve experienced it in my career, and I’ve seen it in action in some places I’ve worked.”

Editors Bear Responsibility for Promoting Diversity

Editors play a key role in combating gender disparities in science journalism, notes Helmuth, because they’re the ones who ultimately say “yes” or “no” to stories. Freelance journalist Rebecca Boyle agrees. As a writer, she says, she hopes editors think carefully about how they respond to writers and commission pieces. “It may take more upfront effort on the editor’s part to get diverse voices,” says Boyle. “Instead of putting the onus on writers, maybe editors need to be more proactive about finding writers.”

Editors and publishers can take a number of steps to keep their bias in check and promote diversity in their publications’ bylines. First, publications should recognize that relying heavily on existing relationships and considering only the pitches that come over the transom are likely to preserve existing disparities. “You don’t have to be actively sexist to perpetuate sexism,” Helmuth notes. She says editors should seek out new writers, especially those who may not be part of established writer-editor networks: Female writers, writers of color, writers with disabilities, LGBTQ writers, and writers from non-Western countries all have valuable perspectives to share—and many may lack direct, personal connections to editors. (This lack of connection to editors may partly explain why, in our survey, women were more likely than men to say that they cold-pitch editors—in many cases, they may have no other option.)

Helmuth also recommends that editors spread the word that they’re accepting pitches through social media and journalism organizations, and that they actively look for new writers by reading other publications. “Expand your reading diet,” she says. “Seek out publications you don’t usually read, and intentionally seek out women and people of color. Get in touch with writers whose work you’ve seen elsewhere, and encourage them to pitch you.”

And if you like a writer’s pitch, try to see that writer’s long-term potential and foster it, no matter what gender they are. Morello says that all editors face an upward battle in finding reliable, talented freelancers to work with, and that investing time in cultivating strong writers is time well spent. After reading about the Science Byline Counting Project, Morello says her team at Nature saw room for improvement. She says she’s making more an effort to identify promising early-career writers and “bring them along” by providing more intensive, detailed feedback in her responses to pitches and story edits.

Even editors who have the best of intentions to work with more women and writers from underrepresented groups find that it can be hard to overcome their own biases. Shreeve notes that he’s been “proactively looking for women writers,”—but it turned out that wasn’t enough. After the results of the Science Byline Counting Project were published in early 2016, he says, “I looked at all 10 years I’ve been editing at Geographic and was shocked to find that among the new writers I’d brought in, there were twice as many men than women. I’m bringing in more male writers while thinking I’m bringing in more female writers!” Now, Shreeve says, every time he assigns a story to a writer, he asks himself why he’s picked that person. “If it’s a man, I ask myself, ‘Why am I giving it to a guy?’”

Even if editors are not intrinsically interested in hiring women and minorities for parity’s sake, doing so can be advantageous for a publication. “If you’re mostly working with established white men, you’re missing out on a lot of great stories that other people will get. But if you work with writers who aren’t being used by the big glossies, you can publish circles around [other outlets],” says Helmuth. “If editors aren’t using the full pool of talent, they’re missing out on some of the best stories and voices—and harming their own publications.”

Statistical Analyses:

- Not significant: gender difference in years of experience: t(220) = 1.12, p = .26

- Not significant: gender difference in number of hours worked per week: t(216) = -.35, p = .73

- Not significant: pitching strategy includes cold-pitching new editors: Χ2(4, N = 222) = 1.97, p = .16

- Significant: pitching strategy includes cold-pitching new editors: Χ2(4, N = 222) = 12.97, p < .02

- Not significant (Fisher’s exact test): ever push back on a rejected pitch: p = 0.097, odds ratio = 0.6362, N = 222

- Significant (Fisher’s exact test): push back by suggesting a different angle: p < .05, odds ratio = 0.3253, N = 79

- Marginally significant (Fisher’s exact test): pushing back on a rejection sometimes, frequently, or almost always results in an assignment: p = 0.06 (N = 112)

Special thanks to Robin Mejia for early assistance with statistical planning and to Kristi Lemm for expert consultation on analyses. Any errors remain the responsibility of The Open Notebook.

Jane C. Hu is a TON fellow sponsored by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. She is a freelance writer based in Seattle, Washington. Her favorite stories usually involve brains, animal cognition, language, or the intersection of science and society. Her work has appeared in Slate (where she was an AAAS Mass Media Fellow), The Atlantic, Nautilus, and other publications. You can find her on Twitter @jane_c_hu.