It’s an assignment that evokes equal parts dread and adrenaline rush in a reporter. Go to an American town devastated by a drug epidemic that led to the largest HIV outbreak in U.S. history. Once there, knock on doors and ask people, including those using drugs, to share their stories with you. Along the way, try to figure out what led to the heartbreaking conditions plaguing this town—and what might help stop the scourge.

For her Mosaic feature “Austin, Indiana: The HIV Capital of Small-Town America,” Brooklyn, New York–based freelance journalist Jessica Wapner spent a week in a town devastated by drug abuse: In Austin, an estimated 12 percent of the population is addicted to drugs. She drove her rental car around blocks of dilapidated houses, finding ways to start conversations—keenly aware of drug dealers watching her watching them. Wapner’s shoe-leather reporting led her to a tale packed with sharp, shocking details of daily life for people living in this economically unsteady town. Her reporting also led her to the field of syndemics, which studies how certain problems—such as physical illness, poverty, violence, domestic abuse, drug abuse, and depression—can grow so “synergistically intertwined” within a population that they become inseparable.

Here, Wapner shares with Kendall Powell how she worked up the courage to knock on those doors and why she enjoys writing about the clashes that happen at the intersection of health, medicine, society, and culture. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

How did you first decide to do a story centered on Austin, Indiana?

The story never would have happened without Jim Giles, an editor at Mosaic I had worked with before, who pushed me to find it and pushed for it with the magazine. I was talking with him about the opioid-abuse epidemic. One of us brought up Austin, but I thought, “Oh, but there was already coverage in The New York Times about the HIV outbreak there.” Jim encouraged me to think a bit more about a story looking at this town.

I had heard about multigenerational drug use—grandmother, mother, and child using drugs together—and that for me became a galvanizing point. What has to happen in a town, in a community, in your support system, for that circumstance to become a possibility, where the barriers to it are no longer strong enough?

That was the pitch: How could this have happened? But then I needed to find what research was out there asking that question. I did not know about this word syndemics before I had learned about Austin. But as I talked to some people in Austin and started researching relevant public health approaches, I put together this story pitch about Austin and understanding it through the lens of syndemics. Syndemics sees clusters of issues, not isolated problems, and seeks to understand a given disease or condition by unraveling the tangled web of issues that it is part of.

How did you find people in Austin to interview?

I had interviewed a public health nurse and the state health commissioner as part of reporting for the pitch. I wasn’t in touch with any local Austin citizens beforehand. I just booked a hotel room with a little kitchenette in nearby Scottsburg.

Austin’s residential area is pretty small. So each day, I would drive into town, stop at houses, and knock on doors. The first day was a lot of working up my courage to do that. It’s embarrassing, but I would circle and circle those streets. I had to give myself a limit: “When I get to the end of this block … ,” or, “I’m going to give myself five more minutes to drive around.” I psyched myself up for it. I know seasoned [investigative] reporters are used to doing this, but I was very unaccustomed to it. It was hard to feel nondescript. Every time I parked my car, it was so noticeable. There were no sidewalks, so I had to park on the shoulders of someone’s property.

At one point, I talked with Jim Giles on the phone while sitting in a church parking lot, about how I would introduce myself. The town had already attracted a great deal of media attention, so people were wary. Also, the questions I had were sensitive and personal, and I was a stranger.

I was honest about the fact that I was a writer from New York, but I also tried to convey that I wasn’t there to gawk at the town. I talked about trying to understand Austin. Sometimes after introducing myself I said something like, “I know there’s been some problems here and I’d love to talk to you about that if you have a few minutes.” Or sometimes I’d wait for them to ask me a question. It was good to attempt the self-discipline to not overtalk, but to let them ask me what they needed to know.

The last line of your lede haunted me: “I’ve never felt more scared than I did in Austin.”

It was definitely true—I wouldn’t have written it if it weren’t. But that fear might not be true for all reporters. Also, some people in Austin hated that sentence after the story was published. To them, it might seem insulting, offensive, or baffling, but it was a true statement for me. There were things that were fearful, being there. I mostly didn’t continue knocking on doors when it was dark out. One person asked if I had a gun to protect myself. Another told me to call him first, rather than the police, if I got into a sticky situation.

Austin residents won’t like this any better, but it was also the saddest I’ve ever been on a reporting trip, the most heartbroken I’ve ever been. Driving away from Darren and Jessica’s house, these young adults who’d been exposed to drug use as children, I wanted to take them with me. Doing my job well required a level of distance. But that doesn’t eliminate the urge to stop their desperate situation.

How did you find Jessica and Darren and get them to share so many details of their lives and their addictions?

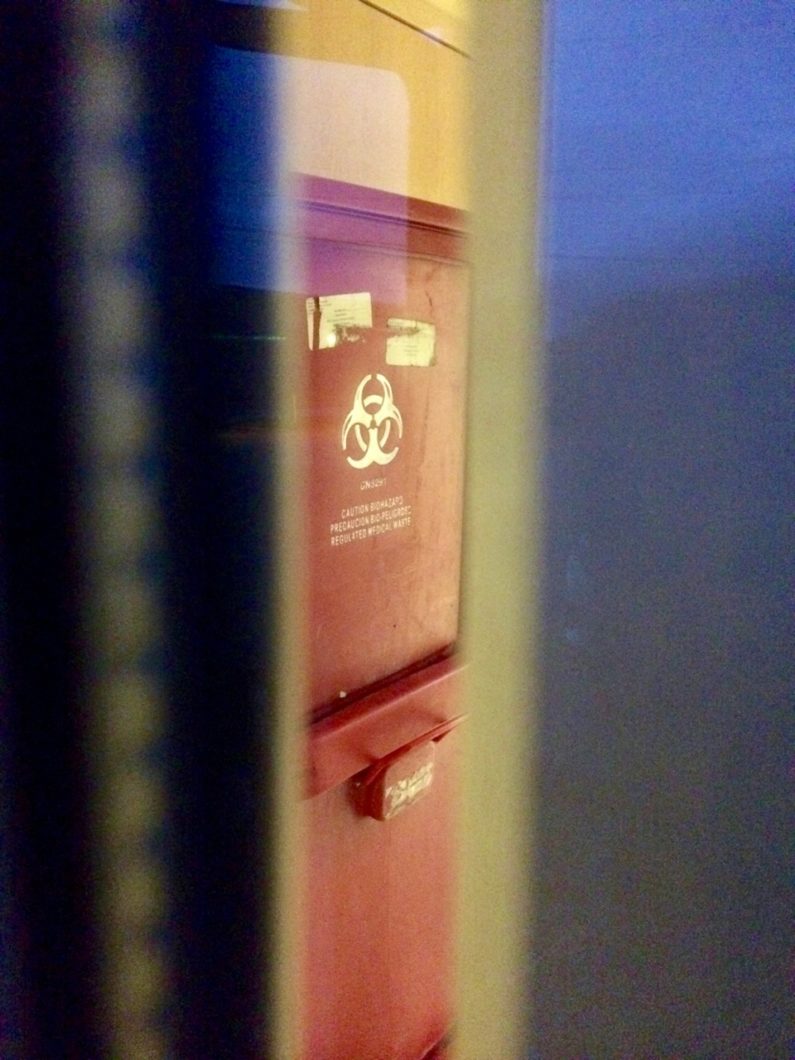

It wasn’t easy to find people who were actively using drugs. During my first few days there I spoke with a lot of people, but none who were actively using drugs, even though most people knew someone who was suffering from addiction or who had died from an overdose. The nurses running the needle exchange let me accompany them in their car on the Friday I was there.

The next day, I went back to one of those houses to try to talk to the people who lived there. I bought a pizza beforehand and had it in the trunk of my car when I knocked on that door. Some people might scoff at that because buying food for sources is against journalism ethics. But I don’t put this approach in that category. I needed some common ground to allow the conversation to begin. It was not about buying someone something so they’ll give you a good story. It was about offering a meeting ground.

At this house that I went back to, Jessica came to the door and said she would talk with me. She told me to meet her in half an hour at her house and gave me the address.

She arrived an hour later and we went inside. Darren had been across the street and he came when he saw Jessica arrive. He just sat right down and started talking to me.

We spoke that day for two hours. They answered all my questions. I kept asking them to tell me if it was too much, but they insisted that nothing was off limits. We had a good conversation, we laughed at things. I was honest: I thought they had been handed a really bad deal by what had happened to them when they were very young.

In the back of my mind, I did think about my safety. Was someone going to show up there angry that they were talking with me? What if they began experiencing withdrawal symptoms while I was there? It was like we were in this bubble where they were completely open with me. The next day I went back and we spoke for another hour and a half.

Was it all sit-down interviews, or did you spend time being a fly on the wall, observing their lives?

It was all sit-down interviews in their living room. I did not spend time observing the routine of their lives. They said a few times that if they’d had Opana to inject they would show me how they did it, but that wasn’t something I would have done even if it were possible. That seemed exploitive, and not why I was there. Also, their lives revolve around getting money for drugs, taking drugs, and being high on drugs. I was there to understand how their lives came to be that way, not to explore the ins and outs of living that life, and not to relay shocking details just so we can all feel shocked.

You paint vivid descriptions of Austin with lines like, “The business with the briskest trade was the gas station, which sold $1 burritos and egg rolls,” and an anecdote about a child mimicking his parents shooting up. How did you capture these details?

This is the value of spending an entire week somewhere. These days it seems like a rare luxury to have that kind of time for an assignment, but this story showed me how vital that kind of time is. And really, even a week is not enough. It’s very presumptuous to think you can understand a place without living there, but these days a week is more than what is usually possible.

All of the details stem directly from having time. I sat with one person on the porch of his mobile home for a couple of hours, and that kind of time allowed for details to emerge, like the child he’d seen with a cloth tied around his arm as if to bulge a vein. A week allowed the time to see the rhythms and speeds on Main Street, to hear many sides to the story, to talk with shop owners and people who’d lived in Austin all their lives.

Before leaving, I made sure to write down a lot of visual information—what different houses looked like, how someone wore their hair. Details I wanted to remember, so that I could bring myself back there later. It never ceases to amaze me how quickly those details are forgotten or mixed up.

The piece is written in first person, and at one point you write that you caught yourself judging the nurses handing out clean needles, “for being so accepting of people shooting up.” Why did you decide to inject your own opinions into the story?

I’ve always felt deeply uncomfortable writing in first person because who cares about my experience? But in this case, that was the story: my effort to understand what was happening in Austin.

Including my judgments was following the trail of how the story unfolded, and it was a useful way to explore the value of the syndemics approach. Some readers might identify with my impressions. The mood during the mobile needle exchange was jovial, not overly serious. And I was thinking, “Wait, why is this feeling okay?” I was judging the lightness they seemed to have about the work they were doing, the kind of breezy way they had in greeting the people they were delivering supplies to. But then I realized that they do this every week, and the attitude they carry is just as important as the sterile supplies.

How did the story change as you worked through drafts?

My first draft was largely about Jessica and Darren. Will Storr, who became my editor after Jim left Mosaic for another job, helped with providing a framework that placed the story of Jessica and Darren, and the Austin that I experienced, inside syndemics research. He did this fantastic “logic map” to summarize the draft step by step. The map of the first draft included: “They take meth. Meth is awful. Meth is really, really awful.”

Much of what Jessica and Darren told me was a living nightmare. I had to write that down for myself, to exorcise that one out of me. But that wasn’t really the assignment. Also, I needed to do more reporting on this field of research, to peel back more layers of that onion. Persisting with interviews and finding published research finally yielded this incredible body of work and enabled me to write a fitting story.

I appreciated the irony in the kicker, where a funeral home director objects to the town’s bad reputation, then rushes off to deal with a drug-related funeral. What made you think to visit the funeral home?

The thought was, “Oh, go to a funeral home and they’ll talk about the number of overdose deaths.” But it wasn’t like that at all. This person said, “This is a wonderful town, my children are having a beautiful childhood here. It’s safe.” That was her experience. I feel for her. Can you imagine having a home where you grew up and then these terrible things are written about it?

Was there anything that got left on the cutting-room floor that you were sad not to have in the story?

I think that all the details that really served this particular story were included. There is more reporting I would have liked to do—for example, about how local politics may have damaged the town, the role played by local physicians, and how health care infrastructure can pose barriers for people ready to enter rehab. I also would have liked to report about other towns experiencing the same epidemic, to know whether the syndemic is the same or different.

Did you get a lot of strong reactions from the people who live in Austin after it was published?

Not tons, but I did get some emails and Facebook messages. One person commented that of all the things that have been written about Austin, this was the worst. A high school freshman wrote to me asking, “Why can’t you write about the good things in our town?” I told her that when I first took an Intro to Magazine Writing class, I said I wanted my beat to be writing about “good things.” I still feel that way. But I also feel there is so much value in looking at the difficulties, the dark corners, to try to understand how those things happen. I responded to her that I was very happy for the experience that she is having and I hope it continues, but Darren had a different experience. One of my questions to her was, “Doesn’t Darren deserve to have his story told?”

I hate the idea that anything I write would ever cause real harm to someone. It’s a part of journalism that I find deeply unsettling. But it doesn’t make me want to stop doing it.

What’s the most important thing you learned as a writer from doing this very palpable, on-the-ground reporting?

I understand more about how irreplaceable it is, first and foremost. I also learned that I want to keep doing it. This was incredible on-the-job training. I hope next time I’ll be a bit wiser, better, braver. I love it. It’s weird to say it that way, because I don’t love seeing people in this state. But I find it the most exhilarating work. I absolutely love being a vehicle for someone’s story and for this kind of science that might shed some light on a problem. I will go anywhere to tell the story that is one more answer to that question of what it means to be human.

Freelance science writer and editor Kendall Powell lives near Denver, Colorado, and covers the realm of biology, from molecules to maternity. She has written for a variety of publications, including The Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Nature, and Discover. She also contributed to The Science Writers’ Handbook: Everything You Need to Know to Pitch, Publish, and Prosper in the Digital Age. She is currently working on her own Mosaic feature about the most common vaginal infection you’ve never heard of. Find her on Twitter @KendallSciWrite.