The best science reporting blends science with art: Writers use words to paint scenes and characters; radio broadcasters and podcasters assemble a mosaic of sounds and voices to capture the essence of a story; data journalists use videos and interactive infographics to support narratives. It seems only natural that science reporting is moving into more visual formats, such as comics and cartoons. While political comics have always had their place in media, science comics have been gaining in popularity and critical acclaim in recent years. I spoke with several artists at the cutting edge of this medium to find out what drives them, how they create their art, and what other science writers can learn from them.

If you grew up reading the daily newspaper funnies or Marvel adventures, you’re familiar with the power of comics. Readers become invested in the characters and what happens to them. “Comics are a storytelling medium at their core,” says illustrator Maki Naro. “They’re a good fit [for a science writing] because science is all about stories.” Naro’s science comics have appeared regularly at Popular Science, The Nib, and Fusion.

Advantages of the Comics Medium

Comics immediately attract viewers’ attention. “People of all ages connect with images more than text on a page,” says Naro. There’s evidence that when we’re casually browsing the web, we’re more likely to pay attention to eye-catching visuals than to blocks of text. And according to digital-asset-management company Webdam, social media posts with images receive 650 percent more engagement than text-only posts. Andy Warner, a nonfiction cartoonist and comics journalist, says a comics format can bolster audiences’ capacity for listening and learning. “Visual elements can build empathy and make it easy to understand,” he says. “Plus, you can include schematics [and] infographics within the comics.”

“People have always used comics to show their identity or make a point.” —Rosemary Mosco

Comics also broaden the appeal of science stories to an audience that may not typically read articles or features. Rosemary Mosco, a science communicator and creator of the comic Bird and Moon, says she’s been able to reach people who aren’t primarily interested in science or nature but are drawn to her quirky, colorful comics. “People have always used comics to show their identity or make a point,” says Mosco. “I used to cut my favorites out of a newspaper and put them on my door. They’re easy to share, so they’re practically built for social media.”

Mosco’s aim is to use that shareability for good. In addition to creating the comics Bird and Moon and Your Wild City (a collaboration with cartoonist Maris Wicks), and a graphic novel, Solar Systems, due out in 2019, Mosco writes, delivers lectures, and gives nature tours at Ithaca College and other parts of the Northeast U.S. She thinks of her comics as a way to inspire action and awareness of wildlife and conservation issues. “My hope is that if I can make people connect to animals and see them in a new light, people will realize they have to take action to help them,” she says.

Similarly, Naro says he hopes his work will show readers some of the untold stories in the science world. He started out drawing comics primarily about silly or surprising science news, but now he’s exploring darker themes like the scientific establishment’s mistreatment of women and minorities. “As you talk to scientists who are women or minorities, you realize science still isn’t welcoming for a lot of people,” he says. “I want to tell stories about people who are trying to fix things; I started trying to focus on what kind of message I wanted to send, and how I could help as a science communicator or a voice for disenfranchised people.”

The Process: Writing and Planning Comics

As with every form of science reporting, a good story is crucial to a successful science comic. Cartoonists and illustrators often draw inspiration from the pool of stories covered by traditional science journalists, then put their own spin on the stories.

Warner draws while listening to audiobooks or podcasts like Reply All, Radiolab, and On the Media, and often finds new ideas from his favorite audio media. “I have a big note document and whenever an interesting story comes up, I’ll flag it,” he says. Likewise, Naro says, fascinating or humorous tidbits he saw on embargoed news alerts on EurekAlert! inspired much of his early work.

Once a comic artist has an idea in place, the next step is writing—and for that, brevity is key. “One constraint of comics, because space is so limited, is the economy of language,” says Warner. Mosco, who earned a master’s degree at the University of Vermont’s Field Naturalist Program, says one class was especially useful in training her to write for comics. “One assignment required us to take a scientific paper and summarize it in 500 words, then in 200 words, then 100 words,” she says.

Naro says he tends to write far more than he could ever use for a single comic. Some of his comics are six or fewer panels, while others are more than 20 panels—but he always ends up with more panels than he plans on. A recent comic Naro worked on was meant to be 24 panels, he says, but he pleaded with his editors for more space. “The Nib was like, ‘We have a limit of 40 panels,’ and I asked, ‘What about 42?’” (It ended up being 42.)

Naro suggests that the keys to writing comics include not only brevity, but also restraint. “Writing is so much about what isn’t written as well as what is,” says Naro. “You could really use visuals to help carry the story—you don’t even have to narrate every panel.”

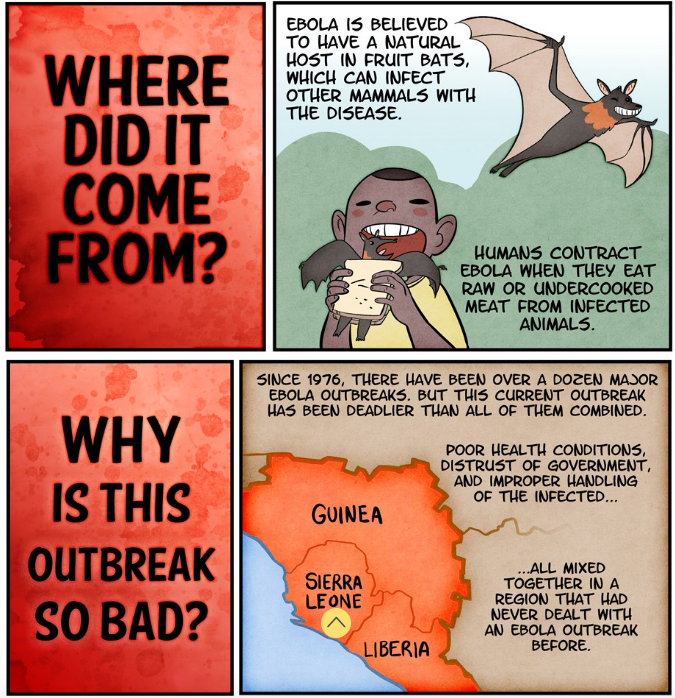

Visuals also help shape the story in other ways. The visual layout of the comic determines the pacing of the storytelling. “Generally, each panel contains its own thought—a beat. There’s a rhythm to it; you’re trying to move people along at a certain pace. Eventually we’re going to get to this big panel—bam!” says Naro. Panels can be different sizes, and the eye is drawn naturally to the biggest panels, which serve as focal points or main beats of the story. In a 2014 comic explaining Ebola, Naro used large, bold text in large panels asking questions about the virus—like “Where did it come from?” and “Why is this outbreak so bad?”—to structure the piece.

And in a comic explaining the patent dispute over CRISPR technology, Warner uses large panels and even GIFs to underscore main ideas.

Illustrators can also use panels that stand out to provide obvious checkpoints for the reader. Deviations from the usual panel, like a half- or full-page panel, or large, colorful text, can flag important concepts. “A reader’s eye will hit [those elements] first, and it can introduce a new big idea,” says Warner. “I end up planning around these.”

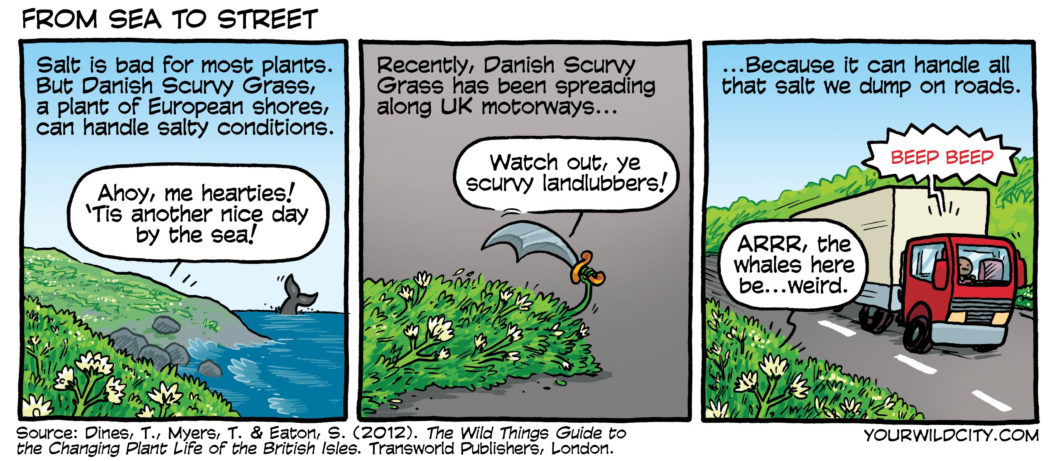

Comics also come alive when they’re populated with memorable characters. “I try to really get into an animal’s head,” says Mosco. In creating a character, she thinks about each creature’s unique traits and what it might say if it could talk. For instance, one Your Wild City strip featured a coastal plant called Danish scurvy grass, which has recently crept inland—and thrived. “Because we pour so much road salt on our highways, this plant in the UK has moved inland,” Mosco explains. “I had this idea to make the plant like a pirate. It was a goofy throwaway idea—a squashbuckling plant with a pirate accent that finds itself on dry land—but the comic did so well.”

The Process: Creating and Editing

Some comics artists post their work directly to their websites or blogs, and others sometimes opt to publish their work on established journalistic platforms that offer more visibility. The Nib is a well-known comics journalism site; other news sites like Slate, Popular Science, and Fusion commission comics as well. When comics artists work with editors, the established process is to send the publication a script and barebones sketch, or “thumbnail,” of the comic. If you’re an editor, this is the part where artists hope you come in with your heaviest edits; while it’s commonplace to ask a writer to rework a few paragraphs in a text story, it’s much harder for an artist to edit multiple comic panels, even with the various digital tools (Photoshop, Illustrator, Wacom’s Inkling Digital pen) cartoonists use for their craft. Naro says that when signing on to a new project, he makes it clear to his client that a contract includes only a certain number of revisions before he charges extra. All in all, the process can take anywhere from a day to a month, depending on the scope of the project.

Like science-writing work, payment for science comics depends largely on the client. Some clients pay per panel, per page, or by entire comic; others pay on an hourly basis. Some independent artists who self-publish their comics, have embraced crowdfunding websites such as Patreon, through which they can offer patrons perks such as early access to new work or PDF copies of each new comic.

Stink at Drawing? You Can Still Start a Comic

Confession from the author: I can’t draw for beans. If you’re like me, you probably read the heading above and assumed this section is for someone else: someone with traditional artistic talent, or at least someone who can draw a straight line. Mosco, Naro, and Warner have all been artists and doodlers since childhood, but you need not be a lifelong artist to create a comic.

Scores of comics deviate from the traditional comic-strip look. Massively popular comic XKCD is all stick figures; Dante Shepherd’s comic Surviving the World comprises photographs of him standing by a chalkboard, where he’s written an observation or joke. Ryan North’s Dinosaur Comics uses the same template again and again, often with surprisingly comedic effects, and absurdist comic Pokey the Penguin looks like it was created in Microsoft Paint circa 2003 with its haphazard copied-and-pasted drawings.

“Good ideas will always trump good drawing—the ideas will carry no matter how bad the drawing is.” —Maki Naro

As a starting point, Warner encourages aspiring comics artists to read widely. “Consume the art form you’re trying to make with a critical eye,” he says. “Read stuff that you like, and think about why you like it—then copy that.” Warner, like Naro, encourages people to use whatever skills they have to create their art. “Comics are much more about design and composition than drawing skill,” says Warner.

Once you’ve grasped the structure and mechanics of creating comics, you can always work with illustrators to execute your ideas. Many graphic novels and regular comics are created through collaboration between artists and writers. While there’s no established marketplace to help writers and artists find one another, online communities like Reddit’s r/ComicBookCollabs and DeviantArt help connect like-minded folks for potential collaborations.

“Good ideas will always trump good drawing—the ideas will carry no matter how bad the drawing is,” says Naro. “Push yourself to see if you can make comics that look good, read well, and clearly—and perhaps the drawing skill will come later.”

Jane C. Hu is a TON fellow sponsored by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. She is a freelance writer based in Seattle, Washington. Her favorite stories usually involve brains, animal cognition, language, or the intersection of science and society. Her work has appeared in Slate (where she was an AAAS Mass Media Fellow), The Atlantic, Nautilus, and other publications. You can find her on Twitter @jane_c_hu.