Is there a science writer alive who has not been schooled by John McPhee? Both of us began our writing careers with a collection of McPhee’s books and articles on our shelves, and over the years, we’ve both returned to his works many times, for pleasure and for sustenance. Writing at The Last Word on Nothing, science journalist Michelle Nijhuis nails McPhee’s singular influence on science journalists everywhere:

When I’m thrashing through the brambles of a first draft, no story in sight, I have one reliable lifeline. WWJMD? What would John McPhee do to get himself out of this #%&! mess? … Some of his writing is now two generations old, and not, shall we say, of smartphone-friendly lengths. But his work holds up. He knows what readers don’t know they want to know, and he knows how to tell them about it. Those gifts don’t expire.

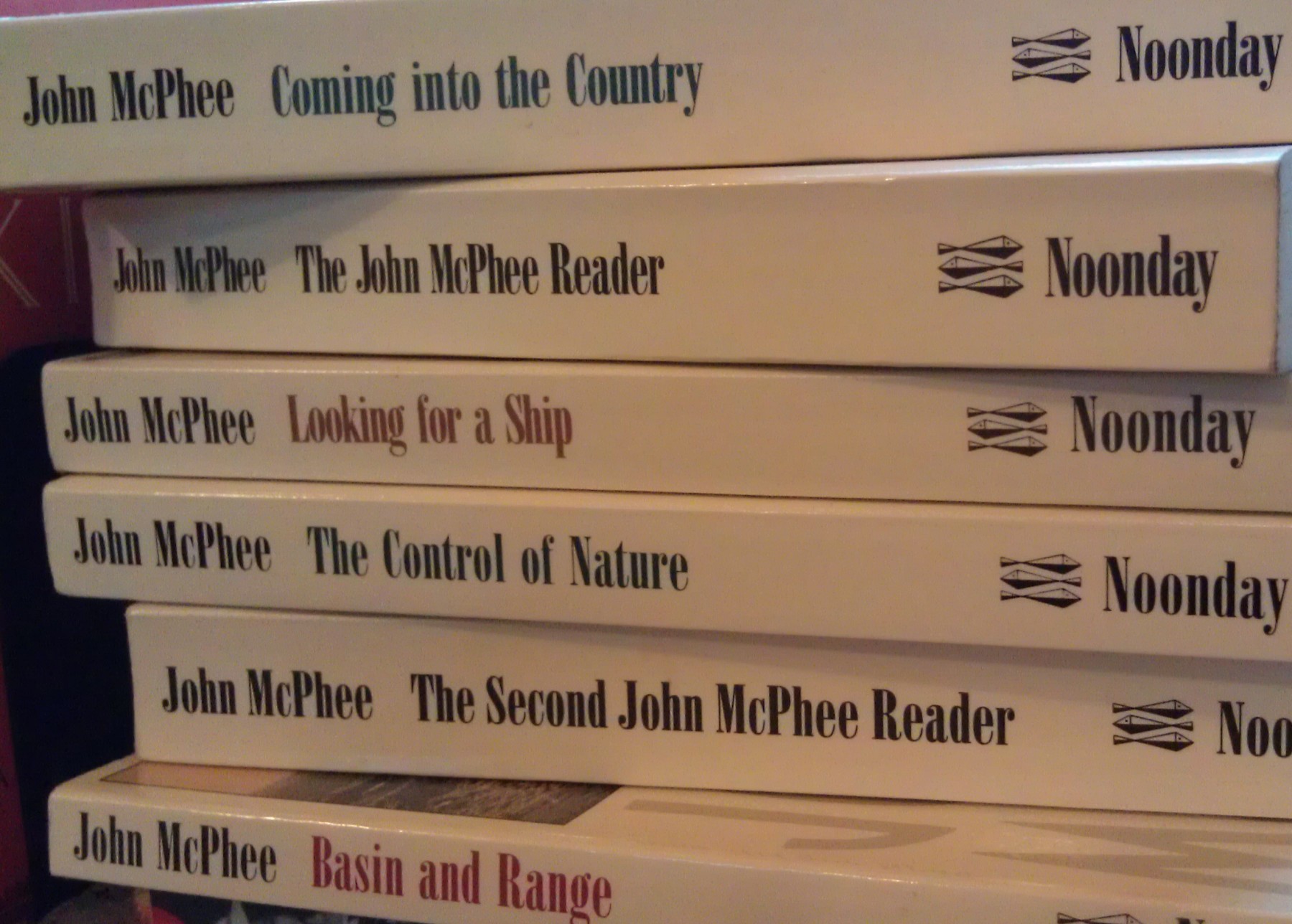

There are a lot of answers to WWJMD, and a lot of places to find them. You can read his books and pore over The New Yorker archives. You can get hold of the charming and instructive Paris Review interview by his former Princeton student, MacArthur award–winning journalist Peter Hessler. Or, best of all, you can hear from the man himself.

Here, Nijhuis presents excerpts from a recent event hosted by the Center of the American West at the University of Colorado-Boulder, in which McPhee read from his latest New Yorker piece, discussing the composition of some of his profiles in that magazine. He then spoke with Western historian Patty Limerick and took audience questions. Below is a transcript of McPhee’s talk, recorded by science journalist Susan Moran and edited slightly for length and clarity by Nijhuis. (An mp3 of the event is available here.)

~ Siri Carpenter and Jeanne Erdmann

Patricia Limerick: Mr. McPhee is known for his extraordinary, memorable characterizations of voices, and that made me wonder if he had ever met anyone too dull to be quoted and made something of. Have you ever met someone too dull to do anything with?

John McPhee: You bet [laughs]. Well, you never know when you start out. You never know when you start a project where it’s going to go. You can only get some conceptual idea, call somebody up, and start in. And sure, it works out that some people are more interesting than others, and some situations are—let me give you two examples. I went down to Valparaiso, Chile, and all kinds of ports in between on a merchant ship for one project. There are 36 people in the crew. If one of them is not interesting, there’s going to be someone who is. The most interesting person on the ship was the captain, but if he hadn’t been, it would have been someone else.

And then, a truck driver read that story and wrote me a letter and said, “Why don’t you come out on a highway with us?” I met him five years later in Georgia. He’s the owner-driver of a chemical tanker leaving for the West Coast. The first thing he said to me—I’d just met him a moment ago—was, “This may not work out. I completely understand and if it’s not working out for you, I will take you to the next airport anywhere, and don’t worry about it.” And I got out in Tacoma. It was a great ride. But the thing is, you just don’t know in advance, and that driver very sensitively recognized that.

Sometimes I’ve had pieces not work out at all because they just didn’t gel. But usually you get together with somebody who has a certain expertise and you follow them through their work. You sort of fade into the background and watch them, and it usually works out.

Limerick: Among the hundreds of characters that you’ve profiled, who stays in your mind? Do any of them appear in your dreams?

McPhee: I guess they have. Very little, but they have. I can’t even remember who. People stay in your mind, like that truck driver—who’s no longer alive. He died last year, fairly young. But I used to call him. He lived in his truck, and I would just go, “Where are you, Don?” “Ten miles east of Abilene,” he’d say, and we’d just talk and talk. So some you keep up with a great deal, and others you don’t.

Limerick: How have your subjects responded? Has anyone been deeply miffed?

McPhee: Oh, yes. And the reasons for the miffing are not always clear to me. For example, I wrote about the Scottish island where all McPhees once lived. And these people were outraged when The Crofter and the Laird was published. That was 35 years ago or something. Now, I think the only remaining copies of that book are sold on the island by those people.

I thought Clark Graebner, the tennis player [profiled in Levels of the Game], was going to kill me. I was in a locker room on the tennis circuit after the article had been published, and I thought that Clark would not be happy. And he says, “Is that going to be published as a book?” And I said, “Yeah.” And he said, “Will you send me a copy?” So there’s no predicting reactions.

Limerick: Has anybody said that they understand themselves better, or that they profited from being profiled by you?

McPhee: I was told that Clark said that. He didn’t say that to me, but I was told by somebody I really believe that Clark himself said that.

Limerick: Has anyone profiled you in a way that you found…?

McPhee: [laughs] I wouldn’t let it happen.

Limerick: That’s what I wondered. That’s what I thought.

McPhee: Well, The Paris Review does these author interviews, you know. And Pete Hessler proposed that he do such an interview with me. Pete Hessler was a student in my writing class at Princeton in the early 90s. Pete Hessler is about the best non-fiction writer that we have anywhere. He has lived in China—I don’t know if you’ve read his books—he’s written three books about China, a wonderful trilogy about China. Pete wanted to do this interview for The Paris Review, so I said fine. He came to Princeton to talk to me, and the interview was 40 pages long. That will do.

Limerick: Staying on the theme of how you select topics and characters, could you tell us about how you chose the three case studies for The Control of Nature? There are 50 million possibilities.

McPhee: Well, you know when I started that I had the idea of doing a kind of endless series of control-of-nature pieces, but as it turns out I did three. I did them simultaneously. They were all written before the first one was published, and there just turned out to be three. I was down in Louisiana with one of my daughters and a schoolteacher I knew. We were out in the Atchafalaya Swamp. The struggle down there between the Mississippi River and the Corps of Engineers is epic. The Mississippi wants to take a right in upper Louisiana and go down the Atchafalaya River. Across the past 5,000 years and more, the Mississippi River has been like one hand playing on a piano back and forth as the main channels switch. And this spread like this has built the entire southern part of Louisiana, the lower half.

The Atchafalaya would have captured the Mississippi 30 years ago. But the Corps of Engineers built two gigantic valves, sophisticated dams in a way, in the side of the Mississippi. The idea is to let a good deal of water go down Atchafalaya, but not the whole kit. They control it there. They valve the water out of the Mississippi and it goes down the Atchafalaya. There is a navigation lock a couple miles down from these valves where boats that want to go down the Atchafalaya get into the lock out of the Mississippi River and then they drop 30 feet to go down the Atchafalaya. But the Atchafalaya is really ready to take this whole show. That’s where I got the idea for the pieces on the control of nature.

I got the title off a wall at the University of Wyoming. I was walking across a lawn there one day, and I saw that on a wall of the engineering school: “Strive on. The control of nature is won, not given.” I thought, “There’s a good title, because it is perfectly bilateral. It cuts two ways precisely.” So, that’s probably why I wrote this whole thing. But then, having gotten into the Atchafalaya story, a Corps of Engineers geologist said to me, “Well, if you’re interested in writing pieces like this, you should think about the debris basins in the San Gabriel Mountains above Los Angeles.”

He put me in touch with a geologist named Keller, and that led to the piece that was called “Los Angeles Against the Mountains.” When I was talking to Keller in California, he said, “Well, if you’re interested in doing pieces like this, you should really think about the eruption that occurred on the island of Heimaey in Iceland. It is Iceland’s second most important fishing port, and the people there fought the red lava with fire hoses and saved their port. So, I went to Iceland and did that. I wrote all that up and that’s The Control of Nature.

Limerick: You are unparalleled, I think, in your achievements in showing scientists as complex people. How did you find geologist David Love [the subject of Rising from the Plains]?

McPhee: Well, I’m not a scientist myself. I studied geology as an elective when I was young, and I really liked geology. All through the years in my pieces, geological points would come up, and I would call a geologist at Princeton and get him to tell me stuff and then get it into the piece. One time I was in Alaska—there is a lot of gold country up there, and I spent most of my time in Eagle, Alaska in the bush up close to the Canadian border. Placer mining was still going on in that region of Alaska where I was.

I was writing about gold, and I understood that erosion sends gold into the stream in little bits, and people pan it and all that. Then I began to wonder: how does gold get into the mountains in the first place in order to erode out? I had never really thought about that, and I called up a geologist named Erling Dorf and asked him that question. And he said, “Look, my specialty is Jurassic leaves.” He said, “I don’t know. Ken Deffeyes knows or thinks he does. Call Ken Deffeyes.” I didn’t know Ken Deffeyes, but Ken Deffeyes became the pilot of all the geology work I did.

The way it came about was that a few years later, I wanted to do a piece on an outcrop outside New York for a Talk of the Town piece in The New Yorker. I wanted to write about the provenance of the rock and its age and what was going on, and I asked Deffeyes to do it with me. He said yes, but before we did the piece I said, “Maybe we could do a longer piece. We could go up the Adirondack Northway. There are beautiful exposures of rock there.” And Deffeyes said, “Not on this continent.” He said, “If you want to do something like that, go across the structure.” In North America, as you go east to west you go from one physiographic province to the next. Then I got this idea: Why not go all the way, and do a traverse of the American continent? I had no idea what I was getting into. Twenty years later, I finished that project.

Anyway, Deffeyes went with me to Nevada, where he’d done his thesis. He was geologist number one in the project, and he called Dave Love.

Limerick: Did you ask him to choose geologists because of their amusing characters?

McPhee: No. I don’t think Ken would even think of that. Dave Love was just this great figure in Rocky Mountain geology.

Limerick: I think I’m going to shift towards your remarkable capacity to listen to conflicting points of view and keep your equanimity. There’s a passage in Coming into the Country where you’ve gotten to know the Gelvin family, and they are flying pieces and parts of a backhoe into a remote location to check out the gold potential of a river—and a totally pristine area.

McPhee: It was a bulldozer. It went up the stream in the winter, when the stream is frozen. It was way up in a valley a couple hundred miles northeast of Fairbanks.

[Reads] “This pretty little stream is being disassembled in the name of gold. The result of the summer season of moving 40,000 cubic yards of material through a box, of varying 200,000 feet of bed rock, of scraping off the tundra and stuffing it up a hill, of making a muck-and-gravel hash out of what are now stream-side meadows of blue bells and lupine, daisies and arctic forget-me-nots, yellow poppies, and saxifrage, will be a peanut butter jar filled with flaky gold. Probably no one will actually use it. Investors will draw it into their world and lock it in an armored cellar while up here in these untraveled mountains, a machine-made moonscape will tell the tale.

“Am I disgusted? Manifestly not. Not from here, from now, from this perspective. I am too warmly, too subjectively caught up in what the Gelvins are doing. In the ecomilitia, bust me to private. This mine is a cork on the sea. Meanwhile (and, possibly, more seriously), the relationship between this father and son is as attractive as anything I’ve seen in Alaska—both of them self-reliant beyond the usual reach of the term, the characteristic formed by this country. Whatever they are doing, whether it is mining or something else, they do for themselves what no one else is here to do for them. Their kind is more endangered every year.

“Balance that against the nick they’re making in this land. Only an easy-going extremist would preserve every bit of the country. And extremists alone would exploit it all. Everyone else has to think the matter through—choose a point of tolerance, however much the point might tend to one side. For myself, I am closer to the preserving side—that is, the side the side that would preserve the Gelvins. To be sure, I would preserve plenty of land as well.”

There are not too many outbursts like that in my work. There are a couple of Rumpelstiltskin moments on the environmental side when I fly into a rage about something called the Dickey-Lincoln Dam on the St. John River in Maine. I just exploded—came out from behind some kind of objective curtain and yelled at the end. Generally, I try to let that kind of thing be in the conclusion of the reader.

Limerick: Were you busted to private in the ecomilitia?

McPhee: No.

Limerick: No? What is your rank?

McPhee: Lieutenant Colonel!

Limerick: Well, my goodness, Sir.

Limerick: You brought a passage from Encounters with the Archdruid about not giving an environmental sermon.

McPhee: Yeah, this is just a little short note. I really don’t know when I wrote this or why, because it’s not in one of the books or anything. It’s probably in a note for my class.

[Reads] “In writing Encounters with the Archdruid, I tried to present each narrative in all its complexity, while pulling back from the sort of authorial judgment that would weaken, I thought, the book’s effect. I wanted opinion to derive from the eye of the beholder. I did not want to write an environmental sermon. That would be there in the words of David Brower. Meanwhile, I wanted the gray, in all shades, to be present. And I hoped that readers would enter the scenes, think about them, and come to their own conclusions.”

Limerick: This seemed too tedious to bother with, but then I thought: I can’t figure it out. What is your genre? Are you a nature writer? Are you a sports writer? Are you an allegory and parable writer?

McPhee: I gave up a long time ago about that. I’m a writer, and I’ve been described as all those things—a nature writer, a sports writer, an agricultural writer.

Limerick: There’s a lot of money in that, I understand.

McPhee: What my work has in common is that it’s about real people in real places. I look for real people who are interesting that I can describe, and the places where they live and work, and so forth, and try to do a sketch of that. It’s led me into all kinds of different areas, but absolutely all of it has that in common. I had to label my course when I started teaching, and so it’s called creative non-fiction. What’s creative about non-fiction? Well, you can make a list of the things that, within the legitimacy of fact, you can do: You can arrange the structure, you can do flashbacks, you can do things that I feel are legitimate in factual writing. That’s what I try to get across to the students.

Limerick: As a teacher or an editor, did anybody ever tell you to get a category and stick with it?

McPhee: It didn’t occur to me when I started writing for The New Yorker that it wasn’t just a good idea to write about this that and the other thing. But I did run into some umbrage from other writers and stuff like that along the way. Not badly, though. [Then-editor William] Shawn said one time, though, “You know, there are some problems in managing you,” because of the variety of themes.

Limerick: Would you speak about your teaching, the teachers who helped you in pursuing your literary gifts and how your own teaching reflects what your teachers did for you?

McPhee: I had a teacher in Princeton High School, Mrs. McKee, who had us write three pieces of writing a week. She had us get up and read them to the other kids, who would wad up paper and throw it at us when we were doing our reading.

We had a lot of fun in that class. We could write anything, fiction, non-fiction, poetry. Whatever it was, the structure had to be defended. You had to turn in, with each piece, a structural presentation, an outline, or a doodle of some sort that showed that you were thinking about the anatomy of the piece when you were writing it. And so, every single Princeton kid that I’ve ever taught has turned in every piece with a structural outline. But I picked that up in 10th grade, or 9th grade. She was a very influential teacher.

Limerick: You could have retired from teaching a while ago, but you are…

McPhee: Listen, they keep me alive.

Limerick: Then don’t retire from teaching, then. Don’t even bring that up.

McPhee: All these people are the same age, and I’m not. Each year, they’re sophomores and all I can do is go from year to year and hope it works out next year. It worked out in 2011, and I hope it does in 2012. It’s like a ship leaving a pier. The pier is solid, and the ship moves away. I love teaching, and wouldn’t feel comfortable if I weren’t doing it.

Limerick: Are there any special or particular or maybe even unusually attractive qualities about writing about the American West?

McPhee: Well, I think that the quantity of projects shows that, particularly if you include Alaska—that was about a three-year project. The geology is more Western, well, more of the geology is west of the Mississippi River, anyway. But all the Western states—Colorado, Wyoming, California—have been a resting place to me. I loved going on those trips. One of the most recent ones was going out to the North Platte and getting myself on a coal train. That was only a couple of years ago. It’s very hard to articulate. But if I were picking one region of the country I could write about—if somebody said, by fiat, you can’t write about any other, I’d pick the West. No doubt about it. The West and, I would say, Hoboken. [Laughs.]

Audience question: When you confined two people with opposing views in one place, as you did with [Sierra Club executive director] David Brower and [U.S. Bureau of Reclamation commissioner] Floyd Dominy in the Grand Canyon, did you find that they were able to come to some type of agreement and better understanding of one another?

McPhee: They said that they did. When they were together, they remarked that being pushed together like that diminished the distance between them. I was a little surprised by it. I was particularly surprised by Brower and [developer Charles] Fraser on Cumberland Island, because Brower practically sounded like a real estate developer before they were finished.

Audience question: You do such a great job capturing people’s voices. I’ve always wondered: do you take notes by hand as you’re talking with them, or do you have recorders? How do you get such great phrases out of them?

McPhee: I’m just listening. Tons of stuff streams by, and I’m obviously not using 100 percent of it, but I do use a tape recorder if I have to. I never try to remember later what they said. There have been writers writing non-fiction who claim that they went home at night and wrote it down. I don’t do that. I scribble constantly. If I’m climbing up the North Cascades, I have a notebook in my hand, trying to keep my balance, and I’m scribbling, scribbling, because I much prefer to scribble in the notebooks than to transcribe endless tape.

But if you have 15 Appalachian geologists of the first rank standing around some outcrop, arguing about exotic terrains in Vermont, the language is unbelievable. I take out a tape recorder and put it on the outcrop. And then I go through the whole process with the thing with the foot treadle and all that to type up the taped stuff. But my first go is a notebook.

Audience question: My introduction to you was your first book, A Sense of Where You Are. Could you replay a bit of the conversation that led to the title?

McPhee: Titles are so key. A Sense of Where You Are was about Bill Bradley when he was a college basketball player at Princeton. He’s 12 years younger than I am. I wrote about him when he was a senior at Princeton. The previous summer, he came to Princeton for week or two for some reason. We’re in the gym, just the two of us, and I was feeding basketballs to him while he goes around a circle shooting, and then he gets in this shot up close to the basket where he just chucks it over his shoulder and it goes in the basket. And I said, “How do you do that?” And he said, “You don’t have to see the basket when you’re in close like this. You develop a sense of where you are.” And then I flopped onto the floor of the gym where the notebook was to write that down—I did that quite a bit with him.

Actually, titles mean so much to me, and editors try to fool around with titles. I get tense about it. In that case, that was my first New Yorker profile. I turned it in with no title. [William] Shawn bought this piece, and then I got proofs, and when the proof came back it said “A Sense of Where You Are.” Shawn had chosen that. He liked titles that came from dialogue. So, he’d picked that, and I’m really grateful to him for that.

I had a piece called “Oranges” a couple years later; “Oranges” was my title. Shawn wanted to change the title to “Golden Lamps in a Green Night.” It’s a line from [the poet] Andrew Marvell. He wasn’t consistent in picking quality titles. In fact, “A Sense of Where You Are” is the only one. I think a title is a huge part of a piece, and when editors think they can just nip a title off at the last minute and put something else on, my back goes up.

Audience question: I’m wondering if you enjoy the process of reporting or researching more than the actual writing. Is there a conflict there? Also, I was told at one point that you would put the whole book on a series of 3-by-5 cards and organize it that way. Is that accurate, and if so do you still do that?

McPhee: Yes. It’s the whole book in the sense that I’ve reduced the notes to little things like airport codes. It means something to me and they relate to components of the story. On the 3-by-5 card there’s nothing more than one word, or half a word, but I know what it relates to. It relates to a whole body of stuff. Then I move the cards around to see where I’m going to find a good structure, a legitimate structure.

About that other point: There’s a big difference between riding a coal train through Kansas and Nebraska and trying to write. Writing is a suspension of life. I believe that so-called writer’s block is something that any writer is going to experience every day, but in a minor way. You break through some kind of membrane, and then you go into another world. Time really goes fast in there, but it is hard as can be to get there, and it frightens me. It frightens Joan Didion. She talks about the “low dread” she feels looking across the room at the door of her study. When she’s sitting somewhere, not writing, and she looks and sees that door, she experiences the low dread. Oh boy, do I know what that means. Getting past it is just a daily thing. It’s not there when you’re riding around in a train, but it sure is when you’re trying to write about riding around in a train.