David Quammen has been one of the world’s leading science writers for over a quarter century, with eight acclaimed nonfiction books, including the iconic The Song of the Dodo, as well as four novels. His new book, Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic, gave us the excuse to interview him for TON—twice.

Below you’ll find an edited text version of the first of two conversations that Quammen had late last year with TON contributor and advisory board member David Dobbs. The first interview was conducted in October before a standing room-only TON event at the National Association of Science Writers meeting in Raleigh, North Carolina; the second was conducted by phone a few weeks later.

Part I of this interview focuses on the logistics of reporting and interviewing, with some attention at the end to meta-concerns about mysteries versus epiphanies. Part II, which we’ll publish next week [Update: Part II is here], is drawn mainly from the December phone interview and will focus on how Quammen, once finished with reporting and laden with notes, transcripts, ideas, and memories, actually sits down and writes a book such as The Song of the Dodo or Spillover. Our text versions of these interviews were edited by Dobbs from much longer transcripts. On Friday, we will post a video of the TON event in its entirety [Update: The video is here].

I’m pleased to have this conversation, David, as your book Song of the Dodo played a big role in convincing me to write about science. It was the book that convinced me that books about science could have the drive, richness, complexity, and ambiguity of literature—and that science was a rich arena that could and will test anyone who is trying to write well about it.

Now we have Spillover, which, as you put it at one point in the book, is about “the infernal aboriginal connectiveness between us and other kinds of hosts.” You show us how these connections can kill us. You show us some practical things, too, like when you look up at bats flying overheard, don’t open your mouth in amazement, because bats sometimes pee when they fly—and after you’ve read this book, we’ll know, for a deep fact, that you do not want a bat to pee in your mouth.

But we’re not going to talk about any of that. We’re going to talk about how you built this thing. Could you read the passage describing how you were drawn to write this book?

The moment that started me on the road to this book, 12 years ago now, was when I heard about an outbreak of Ebola in a little village in northeastern Gabon, I was in the midst of a long, arduous hike across a forest—I was writing a National Geographic story about a researcher named Mike Fay, who was walking a survey transect all the way across Africa—when at a campfire one night in the middle of Central Africa, I met some fellows who started telling me about the time Ebola hit their village. Their village was a place called Mayibout 2; it was an outbreak I already knew about from the literature.

This one fellow in particular, Thony, started telling me what happened after some boys brought a chimp back from a hunting trip from the forest into the village, and people in the village butchered and ate the chimp—and quickly, within a couple of days, they started getting very sick. [He reads:]*

They vomited; they suffered diarrhea. Some went down river by motorboat to the hospital at Makokou. But there wasn’t enough fuel to transport every sick person. Too many victims, not enough boat. Eleven people died at Makokou. Another eighteen died in the village, Mayibout 2.… To this day, no one in Mayibout 2 eats chimpanzee.

I asked about the boys who went hunting. Them, all the boys, they died, Thony said.… Had he ever before seen such a disease, an epidemic? “No,” Thony answered. “C’était la première fois.” Never.

How did they cook the chimp? I pried. In a normal African sauce, Thony said, as though that were a silly question. I imagined chimpanzee hocks in a peanut-y gravy with pili-pili, ladled over fufu.

Apart from the chimpanzee stew, one other stark detail lingered in my mind. It was something Thony had mentioned during our earlier conversation. Amid the chaos and horror in the village, Thony told me, he and Sophiano had seen something bizarre: a pile of thirteen dead gorillas lying nearby in the forest.

Thirteen gorillas? I hadn’t asked about dead wildlife. This was volunteered information. Of course, anecdotal testimony tends to be shimmery, inexact, sometimes utterly false even when it comes from eyewitnesses. To say thirteen dead gorillas might actually mean a dozen, or fifteen, or simply lots—too many for an anguished brain to count. People were dying. Memories blur. To say I saw them might mean exactly that, or possibly less. My friend saw them, he’s a close friend, I trust him like I trust my eyes. Or maybe I heard about it on pretty good authority. Thony’s testimony, it seemed to me, belonged in the first epistemological category: reliable, if not necessarily precise. I believed he saw these dead gorillas, roughly thirteen in a group if not a pile he may even have counted them. The image of thirteen gorilla carcasses strewn on the leaf litter was lurid but plausible. Subsequent evidence indicates that gorillas are highly susceptible to Ebola.

Scientific data are another matter, very different from anecdotal testimony. Scientific data don’t shimmer with poetic hyperbole and ambivalence. They are particulate, quantifiable, firm. Fastidiously gathered, rigorously sorted, they can reveal emergent meanings. That’s why Mike Fay was walking across Central Africa with his yellow notebooks: to search for big patterns that might emerge from small masses of data.

This passage speaks to the task we writers take on: We look for emergent patterns. But first we need the data. I want you to describe how that scene that you just read got from the field, where you observed it, back to your desk in Bozeman so you could use it in your book. First the nitty-gritty paper-and-pencil question: How do you take notes in the field?

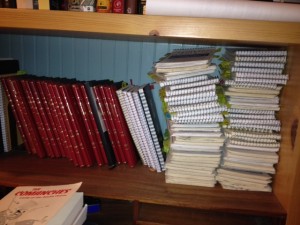

I am very, very old-fashioned and clumsy. I use those long reporter notebooks. This is what a troglodyte I am. The night before I go off on a trip, I take a scissors, I pull out about four of these things and I cut off the bottom inch and a half so this thing is only that long. You know why? Because it fits in a ziplock bag if I do that.

I do a lot of work from jungles, from tropical forests—and my sine qua non field equipment are a ballpoint pen and a chopped-off reporter’s notebook in a ziplock bag. If everything else is gone, if we are swimming across a black lake for our lives, or we are falling down a hillside in the mud, or whatever, I still have my ziplock bag with that one notebook and that ballpoint pen in there.

I know that a trip has been successful at the ten-day or the two- week or the three-week point traveling in Africa or whatever, I reach a point where my notebooks are more valuable to me than my passport. That’s the ideal point. And if you get near the end and you’re still a little bit more concerned about your passport than about your notebooks, it hasn’t been a very good trip.

So when you get home, do you write those up, type them yourself? Or do those stay there and then you later refer to them as you actually write your draft?

I pile them up on my desk. I have a great big stack of them. I also do a daily journal in a little hardback ledger, about this big [he indicates a notebook about 5×8], which is almost exactly the same size as the Penguin novels I like to take along, for reading. The Penguin and that ledger can go together in a different ziplock bag.

So you write in this ledger while in the field?

Usually at five the next morning. I write a journal entry that treats yesterday as a narrative rather than a series of notes. So I have those two things [the field notebooks and the daily journal]. I come home, those are on my desk. I’ve got journal papers and books on my desk as well.

I don’t make outlines. I don’t retype anything. I have [recorded] interviews that have been transcribed by my trusty transcriber, Gloria. I have all these things piled up but what I don’t do because I never went to journalism school—I sort of stumbled into this by trial and error—I don’t go through my notebooks and say, “Here’s an important quote,” type it up and make a whole inventory of what I have.

I don’t make an inventory, and I don’t make an outline. I just pile this stuff up there and then eventually, after three years or four years or so, I start writing. I sit down with all these notebooks and sources and I drink coffee until I go into a trance and I start writing.

With the notebooks, I flip through quickly, typically with a green magic marker, and maybe make a slash in the margin…

These are the field notebooks?

The field notebooks. I make a slash in the margins next to anything that’s interesting. I don’t decide what the structure is, what’s important, what I need to use, what has to fit in – I just make a slash next to anything that’s interesting, So I don’t know exactly what the structure is going to be, how this particular story is going get told in the Ebola section, for instance, until I see what’s interesting and what’s not interesting.

One of my organizing principles, always, is Throw out the boring stuff. If it’s important but boring, leave it out—it’s probably not necessary.

You come back with a lot in your notebook. But sometimes you have to recreate a scene from other people’s accounts—and you still manage to extract a lot of detail out of your sources. There’s one scene in the Marburg chapter, for instance, of a visit two researchers make to a bat cave, wearing full protective gear, which you describe vividly and in great detail even though you weren’t there. [Note: This is one of two other scenes he reads in the full video version.] How’d you get all that? How many phone calls, how long did it take, or did you go see them?

Right. I wasn’t in that cave with the two researchers. I interviewed them later at the CDC [the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in Atlanta, Georgia].

So you what—you asked them a bunch of obnoxious questions, yes? Like “What’d it look like? Did it have a smell? What’d you wear?” Because this sort of detail—well, some people offer those up automatically, but that’s not very common among scientists. You have to ask them.

Yeah, I asked them all the questions I could. And there is some quoted speech in there, but I make it clear in the context that the scene as described is [researcher] Brian Amman’s account of what he said and what John Towner said.

You get as much concrete detail as you can, but—and this is a matter of disagreement among journalists—I show them my draft later on, when the book is done. Three years, four years after I talk to them, I e-mail them and say, “I’ve got a draft of the section with you and Towner in Python Cave. Would you mark it up for me?” I send them a draft in MS Word and I say, “Mark it up and track changes but please understand that I’m not inviting you to second-guess my spin. If I say that you’re an obdurate, truculent, boorish scientist who has done great work on Marburg, then leave that alone but correct the numbers if I’ve got something wrong on Marburg—or if I’ve got the story wrong. If I’ve got the wrong two people in the wrong part of the cave.” It’s very easy to have happen.

So they straighten me out on a lot of that stuff. A few factual corrections and then a few contingent corrections. “No, I wasn’t with him at that point. The guy with me was Allan Kempt at that particular moment.” Very valuable. Otherwise, if you do it without running it past them, then it’s all going to be confused and they’re going to hate it. And if they hate it, then word of mouth in the scientific community is not good, and it becomes harder for the doors to get open next time.

What also comes across in this scene in the cave is the scientist’s engagement here in this scene. They’re in this cave full of bats where a woman contracted Marburg, dressed in Tyvek suits with masks and gloves and so on, and they’re excited, because they’re on a hunt, and they’re getting warmer. You seem to take care to draw your portraits of scientists, even if they’re in the book briefly, as these two are, so that we can see this: They’re on a mission; they have a goal they’re trying to push. A sense of agency drives the narrative and creates tension as well.

Some of these people are heroic, they’re wonderful scientists. I shouldn’t call them disease cowboys; they don’t like that term. But these people, men and women, who go out in the field and study the ecology of emerging viruses… I shouldn’t say it’s one of the great things about emerging diseases, but for a writer, one of the helpful things, one of the enticing things about the subject of emerging diseases is that every emerging disease starts as a mystery. Suddenly people start getting sick in Malaysia: What have they got? Where did it come from? What is it? They find a virus, and it’s a completely new virus. What’s the reservoir host?

In each one of these cases, these different diseases I look at, one of the things that made writing this book so much fun, in its own gruesome way, is that it’s all about mystery stories. Every time. And these people are the detectives. Everybody likes to write about detectives, right?

This gets at something else I wanted to talk about. This scene in the cave delivers something rare within this book, which is an epiphany. Right there in the cave they’re able to trace this Marburg infection back to another source. And there are not many epiphanies in this book. There’s a hell of a lot of mystification. A researcher will find out one thing, get an answer—but the answer just creates more puzzlement. To me this mystification is more true to the progress of science than a book of forced epiphanies, which is far too common. And you make a virtue of the mysteries in this book; you make tension out of the uncertainties. They’re scary. Do you make a conscious decision to do this, or is that tension just so apparent to you that you wouldn’t do it any other way?

I think it’s second nature now. I’m interested in science as a process as well as a source of epiphanies, a source of knowledge, and probably most of you feel the same way. The general public has a tendency to think that science is a bunch of answers, but we know that it’s this very, very challenging, difficult, wonderful human process.

Some of this comes from reading David Hull’s great book twenty-five years ago or so, Science as a Process. I highly recommend it. It looks like it’s sort of scholarly and academic, but it is a history of the rise of cladistics seen as a very human enterprise as well as an important intellectual enterprise. So it’s got all the human stuff that The Double Helix does. It’s a six-hundred-page history of cladistics—but with jealousy and gossip and elbowing your colleagues in the Adam’s apple.

Because that’s how it works.

That’s how it works some of the time. But it also works sometimes with incredible heroism and generosity and concern for your colleagues and efforts that don’t yield epiphanies.

What was the hardest part in writing this book?

What was the hardest part?

Yes. We do not want to hear that it was all easy.

No, it wasn’t all easy. The moments of insomnia, of being wide awake at 2 or 3 in the morning, saying, “How is this going to happen? How am I going to do this? Oh my God, I signed a contract. And my publisher and my agent expect me to deliver this thing.” Those moments came about a third of the way into the research phase, when I was realizing that I wanted to cover everything. I wanted to cover SARS coming out of China, I wanted to cover HIV— how was I going to cover HIV? I wanted to cover Ebola. I wanted Marburg. I wanted Nipah virus, from Malaysia. I wanted Hendra, from Australia. I wanted to get myself embedded with the CDC on an Ebola outbreak.

I’m thinking you missed your original deadline by probably three or four years.

It might have been only two.

I like to go into the field with the scientists and see what they’re doing. I was patient, and it worked out. Eventually people would say, Well, we’re going to Bangladesh in three weeks. Do you want to come with us? Yes!

[Editors’ note: This conversation continues in Part II, where we talk about how laminations, William Faulkner, and an office day-bed help Quammen put all the pieces together into a structured opus.]

*Excerpted from SPILLOVER: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic by David Quammen. Copyright © 2012 by David Quammen. Used by permission of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

David Dobbs is an author and journalist who writes about science and culture for The New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, Wired, National Geographic, and other magazines. His e-book My Mother’s Lover, published by The Atavist, was a #1 Kindle-Single bestseller. He is the author of three other books and writes the Wired blog Neuron Culture. Several of his magazine stories have been included in leading anthologies, including Best American Science Writing 2010 and Best American Sports Writing 2011. Follow David on Twitter @David_Dobbs.