Money. We want it. We need it. But when it comes up in conversation, we freelancers tend to bow our heads and get quiet, leaving the questions surrounding this touchy but vital topic largely unanswered. For starters, how much do people make? How little is too little? What can you do to make more? Can you even make it as a freelancer in this journalistically precarious day and age?

Speculation, personal experience, databases, and the occasional awkward conversation between freelancers (usually over drinks) tend to be the go-to sources for filling in these black holes. But we wanted to dig a bit deeper, and in a way that would benefit everyone.

To do so, we drew upon the freelance science journalist community to provide us with their nitty-gritties on money, and then presented the results in a panel we hosted at the National Association of Science Writers conference in Gainesville. Additionally, freelancers Charles Q. Choi, Virginia Hughes, and Melinda Wenner Moyer joined us to help elucidate the topic. Here, we present the highlights of our freelancer survey and panel for those who couldn’t join us down South.

The Demographics

We started with an anonymous online survey, and gathered participants though social media, listservs, blogs and word of mouth over the course of a couple weeks. We specifically sought people who earned their income as full-time freelance science journalists. We wanted to accurately represent the full-time freelance population as a whole, so we decided to exclude data from around 20 people who reported making $15,000 or less per year, on the assumption that they are likely earning alternative sources of income.

Here’s a break down of the demographics from the final set of respondents:

- Number of respondents: 142

- Gender: 89 female, 53 male

- Top locations: New York and suburbs (n = 39), Washington, D.C. (n = 9), San Francisco (n = 8), Austin and Seattle (n = 5 each). The rest were mostly scattered throughout the United States, but we also had respondents from Canada, the UK, Australia and beyond

- School: 45 percent did not attend school for journalism; 9 percent studied journalism as undergraduates; and 46 percent attended graduate school for journalism

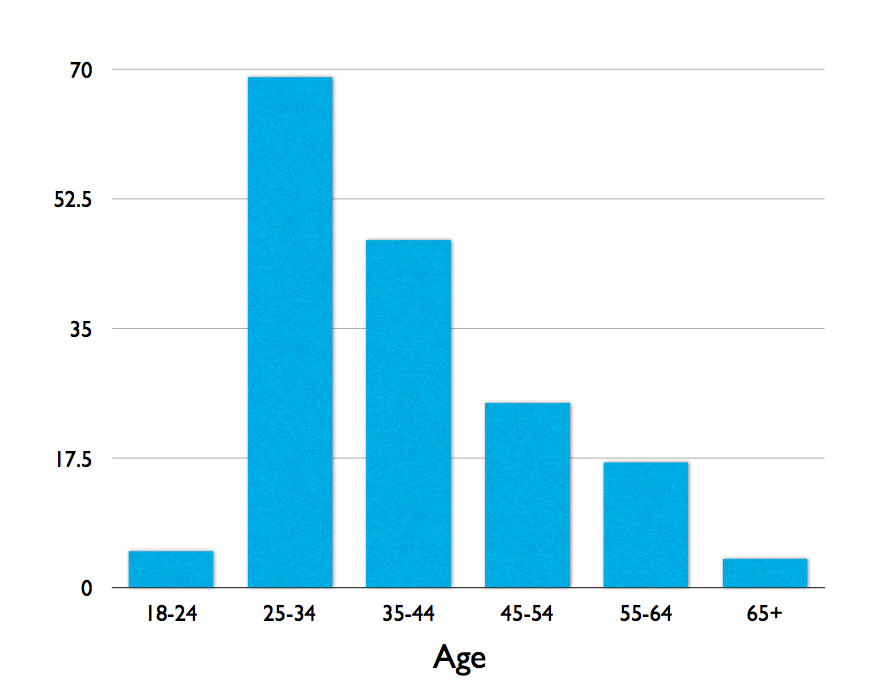

Here’s the age distribution of the people who took the survey:

And here’s the bit on money:

- Average income: $52,500 (standard deviation = $26,400)

- What people thought the average income was: $45,000 (standard deviation = $13,200)

Here, you can see the distribution of income from the survey:

The Stats

With data in hand, we wanted to know what did and didn’t matter for determining a freelancer’s income. What matters when it comes to how much people make? Is it gender, location, age, or education level? Or is it more important how much you make your first year, your minimum word rate, the time spent on various freelancing activities (pitching, writing, researching, etc.), freelancing activities themselves (news stories, blogs, features, magazine articles, etc.), or hours per week worked?

Thomas Altman, an MBA candidate at Tulane University, built a regression model (R-squared = 0.58) to tease out significant trends in the data (an anonymous Tulane professor also looked over the results for accuracy). Altman also used a statistical method called binomial variables—a tactic that economists often use to account for unexpected detrimental events, such as a hurricane or a recession—to control for outliers. In this case, the outlier method applied to any person whose income was more than 200 percent less than the model predicted. Eight people fell into this category; their data remained in the regression, but the model adjusted for the fact that their circumstances are statistically out of the ordinary and might otherwise have skewed the results. With the data now free from potential outliers, Altman used the regression to eliminate, one by one, variables from the survey that did not influence income.

Before we discuss those results, a few caveats. First, our survey was by no means scientific. Participants were not randomly selected, but rather found their way to our survey through the whims of the web. As such, the data skewed toward New York City, where the majority of the participants happened to hail from. On the other hand, representation from some major cities were missing from our data set; Chicago, for example, was nonexistent, while smaller places like Urbana-Champaign seemed overly represented by comparison. Still, our helpful statistician pointed out that the variables identified here are strongly significant, and he suspects they would still stand in a larger and more robust survey.

With that out of the way, here are the five factors we found to significantly influence freelancer income:

- First-year income

- Hours worked per week

- Years freelancing

- Years on staff

- Book editing as a regular freelance gig

Now, let’s break each of those significant variables down, keeping in mind that the specific numbers we cite are not exact because they come exclusively from our dataset. The variables themselves, however, in theory represent what’s driving the broader freelance community’s economics.

First-year income proved to be the strongest indicator of eventual long-term income. The more you make your first year freelancing, the regression indicated, the more you will make in subsequent years. Perhaps how much a person makes in her first year working may capture more intangible qualities that persist throughout a successful career, such as drive, motivation, work ethic, connections and the ability to network and hustle.

Hours worked per week is another significant factor. Not surprisingly, the more you work, the more you make. From this survey, people who work 40 to 49 hours per week make an average of around $12,000 more than those who work less than 40 hours. Amp it up to 50 to 59 hours per week and respondents made $17,500 more than those who work less than that 40-hour baseline. Finally, those who work 60 hours or more make $23,000 more than those who work less than 40 hours. Workaholics are winning, it seems.

The survey also revealed good news for newbies: the longer a person works as a freelancer, the more she will make. But that trend is not linear. Rather, it follows an S curve—incrementally increasing before making a significant jump, and then leveling off again. As Altman pointed out, “it seems income slowly increases with each year of experience, until after 15 years, when it explodes.” Respondents with 3 to 15 years of experience made $15,000 to $19,000 more than those with fewer than 3 years of experience. But those with more than 15 years of experience made more than $30,000 more than someone just getting started. Perhaps this is a nod towards the old 10,000-hour rule.

The results also revealed a seeming sweet spot for holding a staff job. People who worked less than 6 years on staff did not gain any significant monetary benefits and, likewise, neither did people who worked for more than 10 years on staff. However, those who spent 6 to 10 years in an office enjoyed an average annual freelance increase of $16,000. As discussed in our panel’s Q&A session, by the time a staffer reaches the 10-year mark, she or he is oftentimes no longer writing or reaching out to sources. If that staffer decides to become a freelancer, the different mindset involved in scrambling for work and the need to cultivate clients and sources from scratch may explain the lack of benefit from sticking around at a staff job for more than 10 years. (Again, the numbers themselves—6 to 10 years, $16,000—are reflective of the limited dataset, but the “sweet spot” should hold true for the community at large).

Finally, the results did not bode well for book editing as a freelance gig. Respondents who reported book editing as one of their regular sources of income made an average $14,000 less than those who do not edit books.

As we said, these specific numbers are not set. They only represent the 142 respondents who responded to our survey. All of our variables fell within standard deviations and standard errors, meaning there is room to deviate from the average. In other words, just because your cohort makes an average of $30,000 per year, does not mean that you cannot be an outlier. Several anonymous freelancers reported making more than $120,000 last year, for example, and only one of them had more than 15 years of experience.

Now, a few points on things that were not significant. First, according to our data, gender by no means influenced how much a person makes. Likewise, when controlling for years freelancing, age does not matter. Finally, whether a journalist caps her word rate at $1 or more, or has no minimum word rate, did not seem to matter for her net earnings.

A larger data set with a wider and more even distribution would probably reveal other interesting trends. Unfortunately, we didn’t have enough data to test whether or not people in urban centers like New York City or San Francisco make more than those who live in suburbs or rural areas. Two variables—the number of stories pitched versus work assigned directly by editors, and the number of stories pitched versus the number of pitches accepted by editors—both behaved in suspect ways in the model, but neither crossed into the realm of significance. With more data, however, those two points could prove to hold some influence over income.

The Qualitative Points

Although people tend to get quiet when money comes up in conversation, we knew that everyone has thoughts about money. We included a few open-ended questions for rants, concerns and comments, and very informally sorted those answers into categories.

First, we asked, “What is your top concern as a freelancer?” There were three main answers to this question. The most obvious one was money, but we also saw people worrying about client relations, including pitching and both cultivating and maintaining long-term clients, and job satisfaction—pursuing passion projects or longterm goals versus making enough to survive, or becoming too complacent with the same old gigs—also featured prominently.

Next, we asked participants, “Why do you freelance?” More than half said they freelance because of the freedom that life style provides in relation to the workplace—no meetings, picking and choosing their own work, and feeling free to pursue all kinds of projects. Freedom and flexibility in life ranked second, which encompassed the ability to work from anywhere, to spend more time at home with children, or to set their own hours.

Finally, we asked, “What do you wish you would have known about money when you were just starting out your freelancing career or, if you’re a newcomer, what do you most want to know?” Because these answers were so varied, rather than categorize them we’ll share a few highlights:

- “Don’t settle for the initial rate you’re offered. It’s easier to negotiate up front than it is to try to make up the difference later in raises or other changes.”

- “A high per-word rate is nice, but per-word rate isn’t nearly as important as hourly rate.”

- “That it’s hard to make money by writing books!”

- “It’s important to balance quickly paying, quick turnaround work with slowly paying, long-term work. I think a lot of freelancers dream of writing nothing but 4,000-word print features. I did too. But then I realized this is really hard to financially maintain unless you have a lot of cash saved up. Writing print features means getting paid after a long wait and never really knowing when checks will come. I much prefer working on features at the same time as shorter online pieces that pay quickly, so that I always know I’m two weeks away from getting my next check. It’s scary to wake up one day while working on five features and think, wow, I might not get another check for two or three months. Sometimes I get paid a year or more after I’ve written a print feature. SO frustrating.”

- “That you have to pitch a lot, and get rejected a lot, in order to be successful later.”

- “Create a niche for yourself. And once you are well established as being associated in that niche, then you can move on, but first, you must get firmly established. ‘Established’ here means having a strong network that spans two major social networks: i.e., a network like NASW and a nonfiction literary group with prominent authors, etc.”

- “That it takes on average (per my stats) about 75 days to get from when I file a story to getting paid for it. It might have been useful for someone to tell me that building a client list is like building a stock portfolio, that you have to diversify, hedge, and take changes—and be ready to roll with the changes.”

- “Sometimes things happen quickly; usually, things happen slowly. They do tend to happen, however. Expect to erode your way in, not ‘break’ in.”

- “It’s O.K. to take low paying clients, but as you find higher paying ones, dump the lower ones rather than killing yourself.”

So What?

As our results and panelists show, it is possible to succeed as a freelance science journalist. To be a success, our panelists and the NASW conference attendees emphasized the importance of thinking of yourself as a business. Here are some tactics that can help that business of one thrive:

- According to Hughes, all gigs should fulfill what she calls the two-out-of-three rule, meeting at least two out of three of the following points: 1) money 2) career boost or visibility 3) passion project. “Sometimes money trumps all else,” she says. “But I avoid projects at all cost when the answer to all three of those criteria is ‘meh.’”

- Write out a one- to five-year timeline, including the goals you want to achieve in those years. Knowing your goals—both professional and personal—will help you determine the amount of money you want and need to make.

- Think of freelancing in terms of what economists call opportunity cost. “Whenever you do anything, it’s at the cost of doing something else,” Hughes says.

- Balance gigs that pay well with those you are passionate about. Try to do them simultaneously or in succession. “Otherwise, you’ll lose your inspiration and get jaded,” Moyer says. Taking some financial risk on larger projects that may pay off in the future also may help evolve your freelance career.

- Break stories down by how many hours of research, pitching, interviewing, writing and edits they cost you. Use apps such as Hours Tracker if needed. Know how much you want to make per hour, based on how much you want to make per year. Budget for time off for vacation.

- Economists always say diversify so no single loss will impact you. The same applies to freelancing, Moyer says. Choi adds, “Generalists survive mass extinctions.”

- Maintain “bread and butter clients,” Choi says. These are clients you can count on to supply you with work. Keep at least one of these clients, but preferably three. “When you’re that financially vulnerable, it’s very anxiety-inducing if you just have one,” he says.

- Talk to other writers you know about the rates they get paid at various venues. Knowing a colleague is making 50 cents more per word for a certain venue gives you bargaining power for negotiating your own rate (without mentioning that inside source colleague, of course). It’s emotionally harder than logistically difficult to ask for a raise, but it takes just four words, as freelancer David Dobbs sometimes says: “Can you do more?”

This isn’t the final word on freelance money. Our dataset is not perfect, and our discussion did not cover the entire scope of money issues freelancers encounter. This should be an evolving, ongoing conversation. We hope that this will serve as a starting point.