When writers and editors craft a story, we tend to focus first on its tone and texture, its characters and structure—the words that will bring it to life. Being preoccupied with prose makes perfect sense: It’s our job. But for most stories, the words are not what readers see first.

“We don’t like to admit we judge books by their covers, but we do,” says Glendon Mellow, a Toronto fine artist, illustrator, and contributor to Scientific American’s blog Symbiartic, which focuses on “the art of science and the science of art.” Well-chosen illustrations and photography can lure readers into stories, help unpack dense material, and showcase the beauty of many science subjects. These days, with so many options for readers to choose from, especially online, striking imagery matters almost as much as smart, stylish writing to the success of a story.

Often, writers are asked to contribute ideas for art to accompany their stories—or even to obtain it themselves, if a publication lacks a dedicated art department. That means writers must cultivate an eye for the kinds of images that enhance their stories and grab readers’ attention. In practice, it also requires knowing how to find good illustrations and photography, how to use art legally and respectfully, and how to navigate the vast image repository of the Internet.

A-Plus Art

What makes good art? “Number one, it should be aesthetically pleasing, and eye-catching, and maybe a little mysterious,” says freelance writer, editor, and photographer Amy Maxmen. “I almost feel that’s on equal standing as relevance.” She wants her stories to stand out in the crowd, so she selects images that reflect the story’s subject matter, but in creative ways that will pique a reader’s interest.

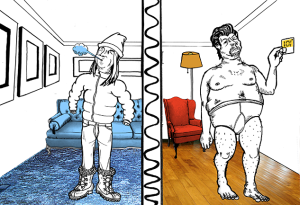

When she worked as an editor at Nautilus magazine, Maxmen worked with microbiologist Jessica Green to produce a story about the invisible life forms that share our dwellings. The story featured an interactive drawing of a Parisian apartment building by graphic designer Steve Green (who is also the researcher’s husband). “If you click on the windows, you can peek into the lives of the people who live on each floor and the bacteria surrounding them,” says Maxmen, who credits the Greens with the inspiration for the concept. Although such elaborate projects aren’t always feasible, she says, they illustrate how writers can have fun with their visuals.

But while a whiff of mystery can be intriguing, art should also convey a story’s message clearly and efficiently, says Robin Lloyd, news editor for Scientific American. Lloyd says the art for Dina Fine Maron’s recent article about in vitro fertilization succeeded because the headline (“New Test Lets Women Pick Their Best IVF Embryo”) and the image—a dividing embryo—reinforced each other. The headline gave the audience a clue that the image probably depicted an embryo, and the art, in turn, helped readers picture the story’s subject.

Best of all, she says, the art achieved this “without requiring a lot of processing thought.” In general, Lloyd opts for art that is easy to “read”—that is, images that aren’t cluttered or confusing and that have a clear center of attention. She also pays attention to an image’s appeal (in this case, the embryo is a warm, inviting pink) and its composition (e.g., the embryo has a satisfyingly symmetric shape, and it abides by the rule of thirds—the objects of interest lie at the intersection of imaginary lines that divide the image into thirds, horizontally and vertically).

If all this sounds overwhelming, Lloyd offers a simple fallback: “Sometimes I just go with my gut when I’m looking at my image options.” She reminds herself that if she stopped at an image, that’s probably because it felt visually compelling.

Beyond Google

In an ideal world, we would commission photographers and illustrators to create compelling custom art for all of our stories. But often, tight deadlines or tight purse strings take this option off the table. Fortunately, the web brims with appealing images of scientific subjects, many of which can be used for free, as long as writers adhere to some simple rules (more on those rules below).

Many writers and editors start by perusing the digital aisles of clearinghouses like Wikimedia Commons and Flickr, which contain a wealth of searchable images licensed through Creative Commons. The trusty Google image search can not only dig up pictures from these sources and beyond, but also filter them according to size, dominant color, and usage rights, among other attributes (see Google’s advanced settings).

In addition, some publications subscribe to wire services or stock-image houses, and independent journalists can use these resources too. Shutterstock offers royalty-free images with very few usage restrictions at reasonable rates (two for $29, five for $49, and an almost unlimited subscription for $199 per year month [CORRECTED 5-13-15]), and features a free photo of the week.

Corbis and AP Images negotiate prices for both royalty-free stock art and photos on a case-by-case basis—depending on whether the image will appear in print, the publication’s circulation, and other considerations. An editorial photo for a web story can cost as little as $100.

On top of these well-known collections, there are other sources of high-quality, freely available images for science stories—if you know where to look. Brian Kahn of Climate Central suggests Getty Images’ vast collection of embeddable photos. Lauren Morello, U.S. senior [CORRECTED 5-12-15] news editor at Nature, finds hidden gems in government archives using this one-stop portal. And as a former geologist who often covers earth science, I’ll plug the European Geosciences Union’s wonderful Imaggeo. (Know of others? Please add more resources in the comments).

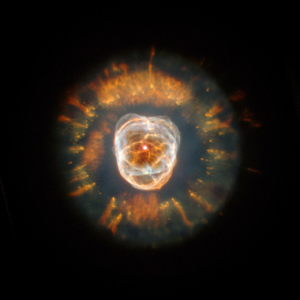

With yet a little more planning and effort, the options grow even wider. Scientists often have useful photos—chances are no one has bothered to ask. For astronomy stories, try contacting the astrophotographers of the AstroBin forum, says Ethan Siegel, the astrophysicist and writer behind the blog Starts With a Bang! “By and large,” Siegel says, “the people involved with that, they just want to say, ‘I created this beautiful thing as a labor of love, and of course I will give you permission to use it.’”

Maxmen encourages writers to troll for images that don’t have Creative Commons licenses on Flickr or Instagram and reach out to the creators for permission to use their work. “Use your journalism skills—Google their name,” she says. She’s surprised how often she gets a positive response. However, if it’s clear the creator is a professional, don’t be surprised if they ask for a fee for their work, just as a writer would.

Hunting for Hits—Legally

Although you can conjure up row upon row of striking imagery with just a few clicks of a mouse, beware the Internet’s low-hanging fruit, says Jonathan Peters, an attorney and journalism professor at the University of Kansas. Peters says many people erroneously believe that any freely available content is also free to use: that if you can Google it, it’s yours. In reality, many online offerings—from images to films to lyrics—are protected under copyright law.

If you can’t license material directly from the creator, which involves negotiating the fee and the terms of use, another option is to choose content registered through Creative Commons. Creative Commons is a nonprofit organization that develops and distributes copyright licenses that allow artists, photographers, and other creators to retain the rights to their work while sharing it freely. (On sites like Wikimedia Commons and Flickr, there is a small risk that users could upload and apply a Creative Commons license to an image that isn’t theirs; Peters says he has found both sites to be fairly reliable.)

Creative Commons offers six flavors of licenses, which stipulate whether works can be modified and whether they can be used for commercial purposes, like advertising. (Peters says news—even when it’s published by a for-profit company—is generally not considered a commercial use.)

If a copyrighted image serves a function greater than just decoration, then including it may be permissible under the fair-use doctrine. The fair-use doctrine permits the use of copyrighted material for purposes of criticism, reporting, and commentary in an attempt to balance the rights of content creators with the understanding that, to some degree, we all rely on the works and creativity of others.

If that notion sounds vague, it is; Peters warns that fair use is a “complicated, sprawling area of law” that even legal scholars struggle to navigate. In general, he says, fair uses add something to the original work, especially if the original required creativity on the part of the creator; they display as little of the original as possible; and they don’t decrease its market value (which would harm the creator). For more details and examples of fair use, check out the second half of this session on copyright law from the 2013 Online News Association conference.

Journalists can also use noncopyrighted works that fall into the sometimes-murky realm of public domain. Most copyrights registered before 1923 have expired, making their content fair game, but beyond that, the rules are dauntingly complicated, as this guide produced by Cornell University illustrates.

Images produced by federal agencies such as NASA, NOAA, or NSF, are the one simple exception—these works can’t be copyrighted, so anyone can use them. However, just to keep things interesting, the same does not necessarily apply to images and documents produced by foreign governments or state agencies, so check before using these.

Importantly, Peters cautions that copyright law still applies if you’re using material that you found on social media. The law generally condones embedding shared content—which entails using a bit of HTML code to display a tweet or a YouTube video or an embeddable image on a website—as long as the content itself was posted by its creator (i.e., not illegally). However, courts do not look kindly on screen shots posted without the creator’s permission. The latter, Peters says, is “the digital equivalent of xeroxing something.”

When in doubt, it’s best to contact an expert, whether a media lawyer or an organization like the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, which offers educational resources, analysis of relevant court cases, and, most importantly, a legal hotline. “You’d much rather have that 15-minute conversation before you get sued than after,” Peters says.

Credit Where Credit Is Due

Regardless of what kind of images you choose to use, it’s important to properly attribute them to the person or organization that produced them. Whenever possible, this includes citing the creator by name, not just noting the source of the image (see this wiki on best practices for images used under Creative Commons licenses; for images licensed directly from artists or stock houses, consult their guidelines, like these from Shutterstock).

Proper attribution isn’t just legally correct—it’s also the decent thing to do. Like writers, artists and photographers put effort into their original creations, and like writing, the end products have value. “At the very least, make sure they get the credit due to them for their good work,” Siegel says. It’s also sound journalistic practice, so that readers know where the material came from.

If in doubt about an image’s original source, Google’s reverse image search (better for obscure images) and a website called TinEye.com (better for images that have been widely shared) both allow you to find previous uses of an image and sort the results by date. “I want to do my due diligence to find the original source as best I can and credit it as far back as I can,” Siegel says.

Picture-Perfect Planning

Copyright categories and searching strategies aside, visually successful stories emerge when writers and editors work together on images from the beginning. As a journalist, Maxmen says, she starts thinking about the art early on in her reporting process and keeps a running list of possibilities.

As an editor, Lloyd doesn’t expect to see images in a pitch. But she appreciates when writers let her know, soon after filing, about “any artwork they’ve come across that they think might work with the story, or if they have a suggestion for an art concept.” In fact, due to the aforementioned nuances of copyright law, Lloyd usually prefers concepts over specific images, unless writers have something from the scientist or have taken a shot themselves.

In the end, the extra effort will pay off. As Lloyd says, “Every bit of data that we have out there suggests that a story that has artwork in an RSS feed or in a Twitter feed or in a Facebook feed is much more likely to get clicked on and shared than a story that doesn’t.”

Resources

Art Sources

- Wikimedia Commons

- Flickr Creative Commons

- Google Advanced Images Search

- Getty Embeddable Images (FAQ here)

- US Government Photos and Images

- Imaggeo (earth science)

- AstroBin (astronomy)

Legal Resources

- Creative Commons license descriptions

- The Center for Media and Social Impact’s Set of Principles in Fair Use for Journalists

- Session on copyright law from the 2013 Online News Association conference

- Stanford’s Welcome to the Public Domain

- Cornell’s public-domain determination chart

- Reporters Committee for the Freedom of the Press

Attribution Help

- Creative Commons’ best practices wiki

- Shutterstock’s attribution template

- Google’s reverse image search how-to

- Tin-eye’s reverse image search

Julia Rosen is a TON fellow sponsored by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. She is a freelance journalist based in Portland, Oregon, and covers earth science, energy, climate, and food. Her work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Science News, Scientific American, Nautilus, and elsewhere. Find more of her work at her website or say hi on Twitter @ScienceJulia.