Structuring long-form nonfiction writing defies simple rules. Sometimes, you should start at the beginning of a story; other times, the middle or even the end. Sometimes you should follow a single narrative as it unfolds; other times, two or more tales tango through an article. The only hard and fast rule seems to be: Do what works. Do whatever will convey the information you want to share while also giving readers the feeling that they’re on a journey—one that might continue beyond the final sentence.

Usually, the most effective structure is also the simplest; the trick is spotting it under the heap of material you’ve gleaned in reporting. Many writers describe wrestling with their notes—aided by index cards, whiteboards, or software like Scrivener—until the answer reveals itself. In a previous TON story, veteran science writer David Quammen says he sits with his pile of notebooks drinking coffee until he goes “into a trance” and starts writing. And in her excellent piece on feature structure, journalist Christie Aschwanden writes, “I don’t know what I’m looking for, but I know it when I see it.”

To beginners, the whole process can sound, well, a little magical. What if we don’t know how to conquer our unruly notes? Or more importantly, what if we can’t recognize the right organizational pattern when we see it? Part of the problem is that there are as many successful structures as there are compelling stories. But that’s also part of the solution: By examining a range of stories, not only can you build a repertoire of possible choices, but you can also develop a sense of which narrative choices work, and why. So we’ve asked four feature writers to reverse engineer some of their favorite tales—their own and those by other writers—to expose their narrative skeletons.

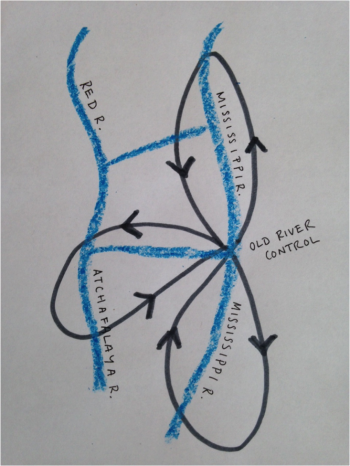

Story: “Atchafalaya,” by John McPhee, published in The New Yorker in 1987.

Drawn by: Michelle Nijhuis, freelance science and environmental journalist

Summary: The story, Nijhuis says, “is about the Army Corps of Engineers’ efforts to break the Mississippi River’s long habit of moving back and forth across the Louisiana coastal plain—and especially to keep the river from sending most of its flow down one of its distributaries, the Atchafalaya.”

TON: What would you call this structure if you had to give it a name?

MN: If I had to give this structure a name, I’d call it Repeated Attempts. The story centers on Old River Control, the set of structures built along the Mississippi at the head of the Atchafalaya. McPhee starts at Old River Control, goes upriver, and returns; starts down the Atchafalaya and returns; goes downriver on the Mississippi and returns; and finally finishes his trip on the Atchafalaya and returns. Toward the end of the story he writes, “My mind cannot help drifting back to Old River, where every part of this story in a sense had its beginnings and could also have its end.” His history of the Corps and the river, which is interspersed with his present-day travels, isn’t entirely linear, either—instead it’s centered on an iconic event, the 1973 flood that almost destroyed Old River Control.

TON: What’s interesting or different about it?

MN: So many stories about rivers—including mine about the Mekong [discussed below]—start at the beginning of the river and follow the current toward its mouth. Which makes intuitive sense, but here we’re talking about a trapped river, one whose hydrology is fighting against human engineering. So it seems appropriate that McPhee keeps returning to the point of tension between humans and the river.

TON: Why does it work?

MN: The structure works, I think, because it serves to emphasize that tension—McPhee’s multiple approaches give the reader a sense of the river’s strength as it batters against Old River Control, and of the Army Corps’ determination as it goes to greater and greater lengths to keep its barrier in place.

Story: “Harnessing the Mekong or Killing It?” by Michelle Nijhuis, published in National Geographic in 2015.

Drawn by: Michelle Nijhuis

Summary: The story is about the eleven proposed dams along the Mekong River in Southeast Asia. It analyzes the tradeoffs between the potential benefits of the dams and their costs, both to the environment and to rural residents who rely on the river for survival.

TON: What would you call this structure if you had to give it a name?

MN: I’d call this one Voyage and Return. I felt I had to pick a fairly simple structure for this story because the story itself is so complicated—it’s about eleven hydropower dams proposed for a 2,700-mile-long river that runs through six countries. So I started the story in northern Thailand, moved downstream to Laos and the first dam site, then moved to Cambodia and finally to the Mekong Delta. At the end I returned to northern Thailand and to a scene depicting the strongest opposition to the dams—I hope that coda not only gives the reader a sense of resolution after the long journey south, but also points toward the future of the controversy.

TON: What’s interesting or different about it?

MN: This isn’t necessarily unusual, but I think it’s important to remember that you don’t have to write your story as you reported it—I reported the scenes on the south end of the river months before I reported those in the north.

TON: Why does it work?

MN: I hope the structure helps the reader understand the Mekong’s complicated and probably unfamiliar geography. I also hope it emphasizes how the effects of the proposed dams accumulate downstream—they get broader and deeper as both the river and the story move south.

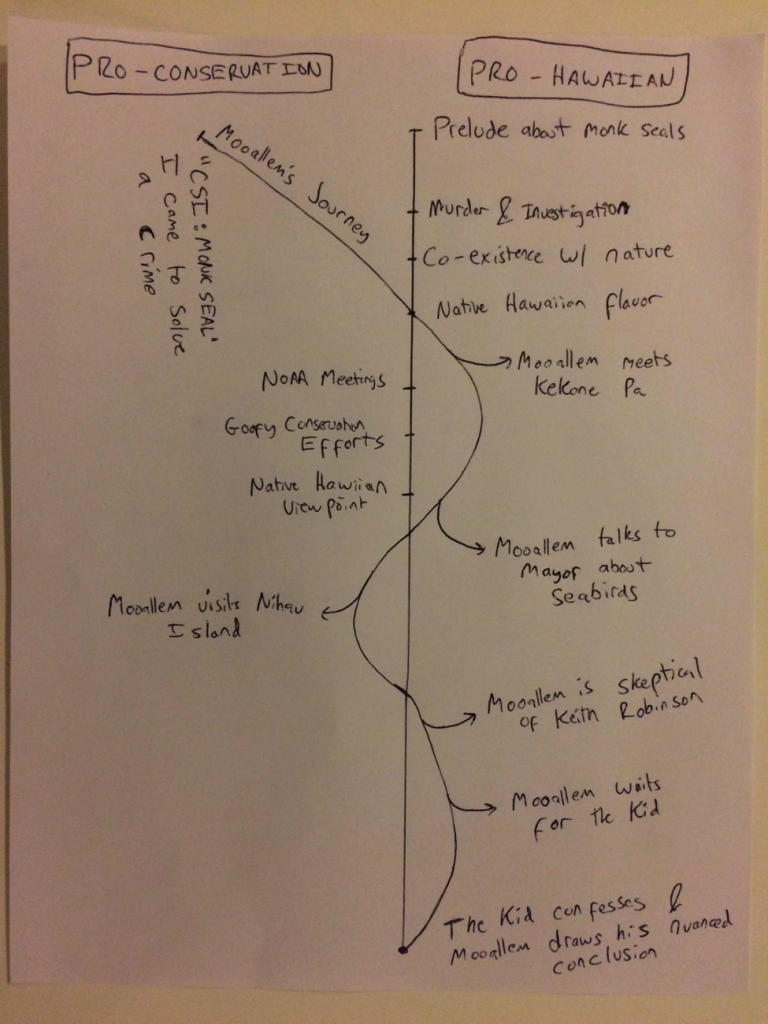

Story: “Who Would Kill a Monk Seal?” by Jon Mooallem, published in The New York Times Magazine in 2013.

Drawn by: Brendan Borrell, freelance journalist

Summary: The story sets out to investigate a spate of monk seal killings in Hawaii, where the endangered seals thrived before being eradicated by Polynesian settlers about 1,500 years ago. The seals’ reappearance—and their protected status—has agitated some Native Hawaiians, who feel that conservation goals are often placed above concerns for locals and their way of life.

TON: What would you call this structure if you had to give it a name?

BB: Detective Story

TON: What’s interesting or different about it?

BB: In many ways, it’s a pretty typical magazine structure, but two things stand out. The first is Mooallem’s meandering style and the way that he introduces characters and scenes as asides. It works really well in this piece because it really has the feel of a detective story, where characters just pop up here and there with a surprising clue. The second thing that stands out is rather than opening on the murder scene, which is an obvious hook, he opens with a kind of expository prelude about the monk seals and what their backstory is. He’s fond of this technique and also uses it in his American Hippopotamus story for The Atavist Magazine. It works because he is such a fine stylist (he calls the seals “the Zach Galifianakises of marine mammals”), but also because he is letting you know that he is going to be your personal tour guide to the story.

TON: Why does it work?

BB: Mooallem has a deceptively casual style of writing, so that even when he is talking about serious and complex topics he pulls you in like a kindergarten teacher during storytime. You just want to close your eyes and listen. He frequently takes breaks from the storytelling to remind you what the story is really about, just in case you nodded off for a second. His style is utterly disarming and he is the opposite of condescending: You can sense his deep and earnest fascination with the people he meets. As for this story, it cuts between Mooallem’s journey as a kind of a goofy Sam Spade character trying to identify the monk seal killers and the history of the conflict between Native Hawaiians and conservationists. As Mooallem’s journey progresses, you feel like you are getting a deeper understanding of the story at the same time he is.

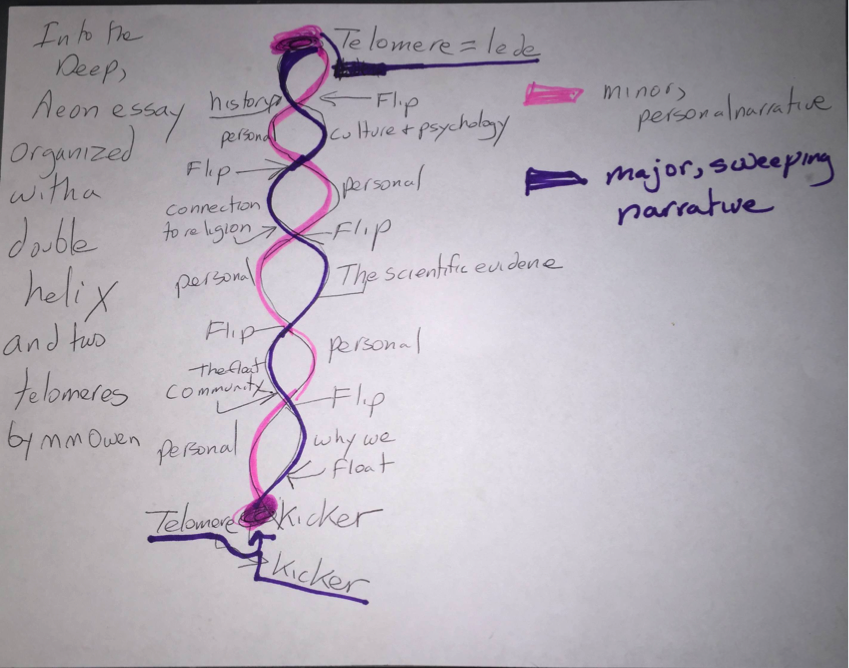

Story: “Into the Deep,” by M M Owen, published in Aeon in 2015.

Drawn (and edited) by: Pamela Weintraub, psychology and health editor at Aeon

Summary: Through the lens of the writer’s own experience with sensory-deprivation float tanks, the story explores the origin and popularization of this technology, as well as the scientific evidence in support of its psychological and physical benefits.

TON: What would you call this structure if you had to give it a name?

PW: Double Helix

TON: What’s interesting or different about it?

PW: Both threads assume a more or less narrative form. The minor narrative (pink) is the personal story, and the major narrative (violet) is the popular narrative, history, and analysis. The pink, or personal narrative, serves as the cap (the telomere) at each end.

TON: Why does it work?

PW: It works because each thread tells its own story, independently, yet the two stories are positioned, by their transitions and their themes and actual content, to complement each other, adding heightened resonance as they flip back and forth. The movement between the two strands in this double helix fights boredom—and the narratives continue to flow.

Story: “The Voice of Reason,” by Pamela Weintraub, published in Psychology Today in 2015.

Drawn by: Pamela Weintraub

Summary: This story explores a range of new research on how self-talk—which people learn to do as children, primarily by imitating the adults around them—can improve performance, increase confidence, and give people a more objective perspective on their lives.

TON: What would you call this structure if you had to give it a name?

PW: Filtered Two-Step. One narrative (the story of the research) is filtered right through another narrative (the evolution of the inner voice through human development) to render a true sense of story.

TON: What’s interesting or different about it?

PW: I was asked to write a story for Psychology Today last year (it was the cover story in May 2015), but the assignment posed an organizational challenge. My editors wanted me to cover, as the core of the story, a particular set of studies on how to talk to yourself. The studies were extraordinary, but because the researchers in question had so much of their work in press, I could not cover them with enough depth to make a feature out of it. And this was to be a cover story!

The trick in a situation like this, where there is no natural through-story but just a collection of (admittedly important, fascinating, and connected) information, is to create the feel of a story through an organizational scaffold that accomplishes two things at once. One element of the scaffold must carry the storytelling itself. The other element must give the information your editors and readers want. My two elements were as follows: 1) I had the story unfold in a natural way by focusing on the development of the inner voice through a human life from earliest childhood on, and 2) I hung the relevant research and information on that scaffold so that it became part of the story.

TON: Why does it work?

PW: By having these two overlapping and intersecting dynamics (the maturation of self-talk through age and the uses of self-talk), I use the organizational structure to create the feel of a story where there is no pivotal event or situation or locale that acts as the focus of the story.

For instance, I start by describing self-talk in toddlers, and I make the point that we can instruct ourselves in accomplishing tasks through self-talk. I can go on to explain later how this “blueprint” for self-talk, developed in childhood, shapes adult self-talk. Adult self-talk can be even more powerful because it can reach beyond the language centers of the thinking cortex to the amygdala, where it can influence emotions. I am still in human development here, but this time the discussion of human development stretches into adulthood and makes the story feel as if it is moving forward chronologically because we are talking about a later part of the human life cycle.

In fact, when it comes to discussion of voice, I have changed the topic utterly—to focus on a less concrete and more emotional and unconscious aspect of that voice in our lives. Yet the story flow does not feel as atomized as it actually is because the structure holds it narratively in place. Through this technique, I manage to meet my editor’s request that I spotlight specific emerging research that is related but not joined at the hip. One could have delivered all this material as a chunky service feature, where the different pieces of information are delivered in discrete sections, as women’s magazines often do. But my organization provided me with a narrative path through—and enabled me to reflect, in a deeper way, on the meaning and importance of the findings as a whole.

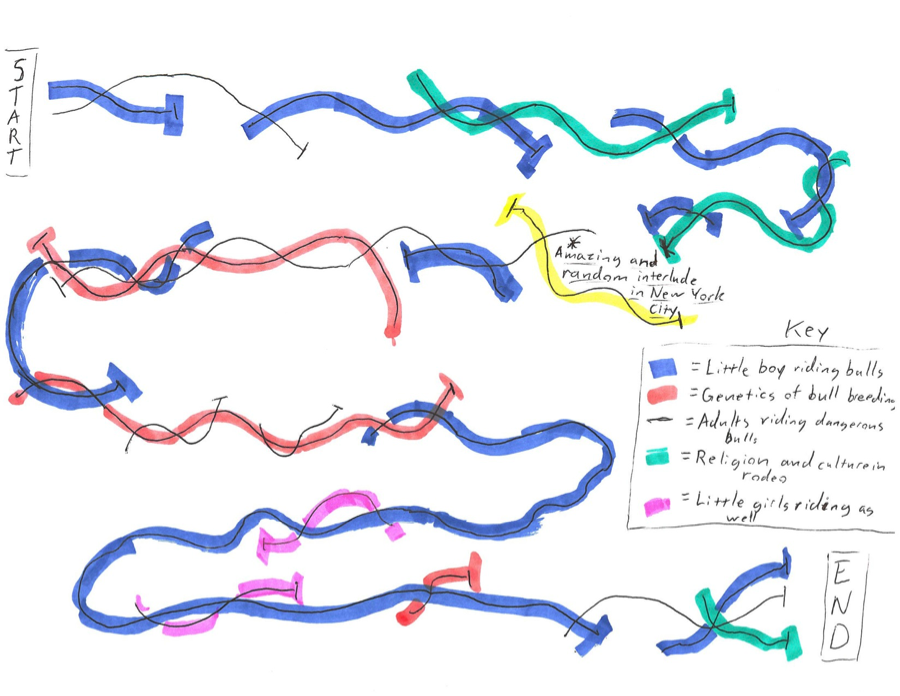

Story: “The Ride of Their Lives,” by Burkhard Bilger, published in The New Yorker in 2014.

Drawn by: Erik Vance, freelance science writer

Summary: The story revolves around a camp where young children train to become rodeo bull riders. As it progresses, Bilger touches on the science of bull breeding, which has created ever-more dangerous opponents for professional riders, and the cultural and religious roots of the sport.

TON: What would you call this structure if you had to give it a name?

EV: The Woven Narrative Braid

TON: What’s interesting or different about it?

EV: It takes the three themes of religion, science, and culture and spins them into a narrative that is coherent and illustrative. Then it takes a random sidetrack from Oklahoma to New York City that against all odds totally works. For a lot of writers, this would just be too tricky and they would get lost under the weight of it. Especially the religion part—you could focus an entire story just on that. Certainly I’d be intimidated by it. But when I asked him about it, Bilger said he clearly saw all three narratives as naturally intertwined. It was as if that was the only way the story worked for him. I think it was that vision—that picture of just how much to say and where—that made it work.

TON: Why does it work?

EV: It works because of the skill of the writer and a clear vision of what the story is. I mean, I see this as the work of a master. There are a lot of things you can dissect about some pieces, this one included. But having tried this kind of work in the past, I know how hard it is. And sometimes you just have to step back and admire good work and talent, you know?

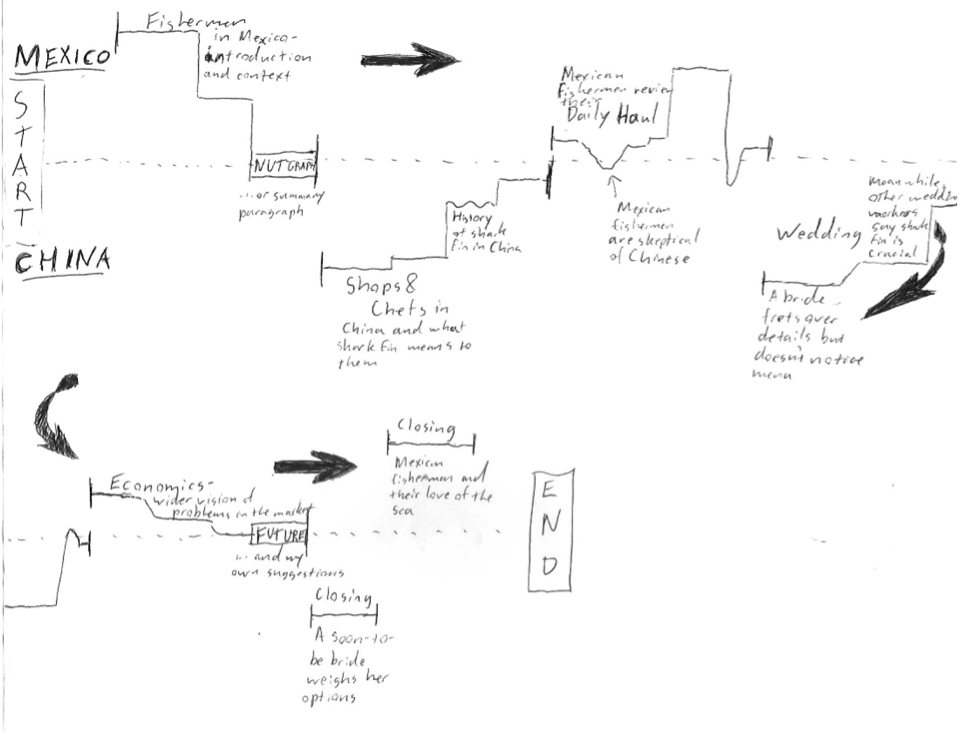

Story: “An Ocean Apart,” by Erik Vance, published in the Virginia Quarterly Review in 2015.

Drawn by: Erik Vance

Summary: The story looks at two very different cultural traditions—shark fishing in Mexico and the consumption of shark-fin soup in China—and their impact on shark populations.

TON: What would you call this structure if you had to give it a name?

EV: A Tale of Two Vastly Different but Tightly Linked Stories

TON: What’s interesting or different about it?

EV: It’s hard to imagine two more different places than Hong Kong and Baja. But the two places are tied together by the fin trade and are emblematic of the cultural and economic tensions that are causing pelagic sharks to vanish. I see these stories being inextricably linked. The trick here was coming up with a way to allow the reader to see the parallels without getting dizzy.

I didn’t want to do a simple “bait-to-plate” narrative because the focus needed to stay on people and culture, not just chain of custody. The image I had in my mind were these two people looking across the sea at each other. I found that sometimes little details allowed me to pass the narrative back and forth smoothly.

For instance, I use a quote from a Chinese shark-fin importer who insists that shark populations are fine in Baja to pivot to a discussion of the health of Mexico’s shark fisheries. Later, I transition back from a passage on the declining market value of shark fins to a Chinese wedding where the bride and her mother express ambivalence about serving shark-fin soup at the reception, but offer it all the same. But at other points, I just allowed the shift to be a little jarring, hoping the reader would find it interesting to shift suddenly.

The number of transitions actually changed a lot while writing the story, which had a very serpentine path to its final publication place and date. The first outlet we (the photographer, Dominic Bracco II, and I) worked with wanted a lot fewer scene switches between Hong Kong and Mexico—almost like two separately developed stories. It felt odd. But when I talked to VQR, they immediately saw that it was one story, just told from two very different locations via characters who would probably never meet each other. I was thrilled to be able to skip around more.

TON: Why does it work?

EV: I think it works because, while these are vastly different settings, they are tied together by characters who want the same thing—prosperity, respect, and a better life. And of course the sharks. This is not about the chain of custody of a fish, this is about what that fish means to two groups of people. The photos were also crucial, carrying a continuous flavor throughout the piece. Because we reported the whole thing together, Dominic and I spent a lot of time talking about what the story meant and what things we wanted to say—his visually and mine narratively.

[Author’s note: Credit for the idea of drawing stories to understand their structures belongs to an English professor I met in graduate school, long-time magazine writer and essayist Ted Leeson.]

Julia Rosen is a TON fellow sponsored by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. She is a freelance journalist based in Portland, Oregon, and covers earth science, energy, climate, and food. Her work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Science News, Scientific American, Nautilus, and elsewhere. Find more of her work at her website or say hi on Twitter @ScienceJulia.