Late last November, something happened on Facebook that happens pretty much every day: An argument broke out over politics. In this particular case, the fight was between two former high-school friends who now live two thousand miles apart. Omar Halama, a state employee in New Mexico, had shared a post that claimed Donald Trump should have won the popular vote in the 2016 presidential election, but didn’t because of “massive voter fraud”—a claim that originated on Twitter, but that still hasn’t been backed up by any data.

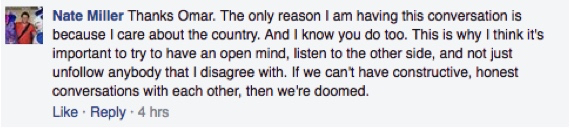

Nate Miller, Halama’s former classmate, now lives in New York where he works in international health. Miller felt inclined to comment on the story Halama had shared: “Do you even care if the things you post are true or not?”

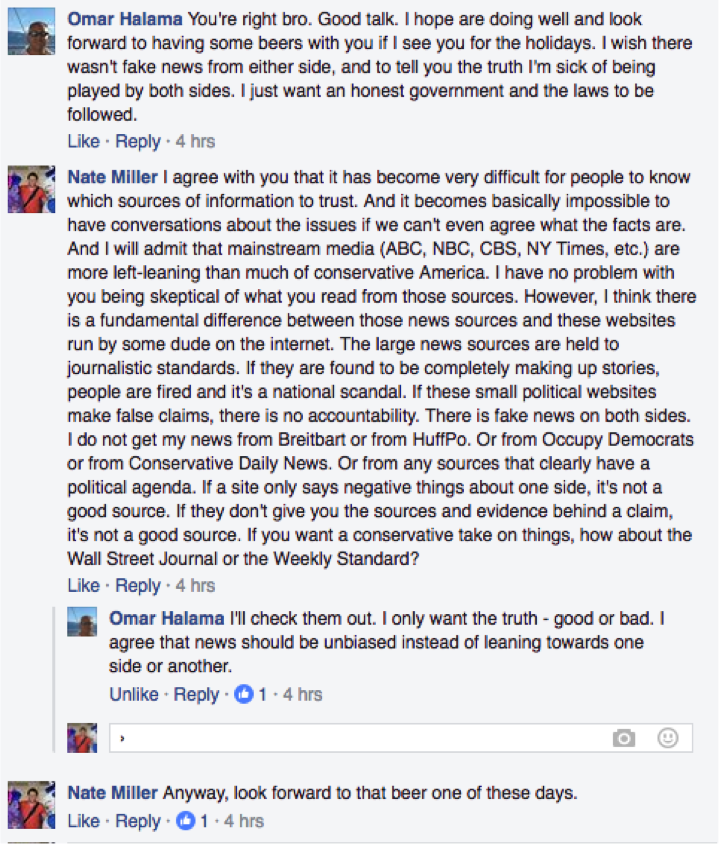

The argument that followed probably sounds familiar to Facebook users who have been on the social media site in recent months: It was pretty heated, and the men traded their own set of preferred sources. Miller contended that the story was fake news, countering it with a debunker from Politifact. Halama posted a second story about the alleged fraud from the Independent Sentinel, which bills itself as publishing “the news that the media doesn’t want you to know about,” and said that mainstream media—ABC, NBC, CBS, and so on—is actually the fake news.

But then something interesting happened.

“The only reason I am having this conversation is because I care about the country,” Miller wrote. “And I know you do, too.”

Soon, the two were in agreement, at least in some respects—both said they want trustworthy sources of information, and neither wants to support “fake news.” And then they agreed to grab a beer the next time Miller was in New Mexico.

In an essay published at FiveThirtyEight last month, I argued that fact-checking isn’t enough to combat false news stories like the one Halama posted, which have been spreading across the Cyber like an uncontrollable cancer. Instead, those who create and consume digital media need to make it harder for fake news to thrive. That includes readers, who bear responsibility for the stories they choose to share and like, as well as the way they interact with one another.

Science journalists and writers may help, in our own social media circles. We are, by training, supposed to be research aces with good BS detectors. “In this world that we are now living in—which is so incredible to [science writers] who make our living dealing in facts—I think it is so important that we stand up and provide background. We fact-check,” says Kelli Whitlock, a freelance science writer who has been experimenting with pointing out misinformation to her Facebook connections. “We do what we can to educate and inform. Because the only way we are going to survive is through an informed populace.”

So, if we see our connections spreading misinformation—whether they mean to or not—can we use our skills to help curb it? Will we alienate our family and friends in the process, or will we still be able to get together over a beer? And does the way we respond to misinformation on social media make a difference? Can we change minds?

I posed these questions—okay, maybe not the beer part, but the rest—to 15 experts, including psychologists, sociologists, communications specialists, and media scholars. Here’s what I learned.

Gallery: Anatomy of a Facebook Debate

Images courtesy of Brooke Borel. Shared with permission of the participants.

The Allure of Facts

As science journalists and writers, when we see fake news on social media, our first instinct may be to correct it. Fact-checking and reason are both key to our job. For years, in fact, the reigning theory for science communication was what is known as the deficit model, which suggests that the way to correct misinformation is by providing accurate information. Knowledge is power, right?

In some cases, this approach may work with fake news, says Leticia Bode, a media scholar at Georgetown University. Research by Bode and Emily Vraga of George Mason University suggests that correcting falsehoods on social media about topics like Zika virus can be effective—whether those corrections come from algorithms, like the “related links” you may see under a post on Facebook, or from a personal connection. The researchers write: “Information from friends might have greater impact, because we trust those closest to us.”

When someone shares a piece of political fake news, it is an act of confirmation bias, an attempt to buttress their existing point of view.

But this tactic can quickly backfire, particularly for people who are susceptible to conspiracy theories. “If you are somebody who is willing to believe in conspiracies, then you are not affected by corrective information,” Bode says. “You buy into the misinformation wholesale.”

The deficit model may fail for fake news in other ways, too. In the broader scheme of science communication, the deficit model has cracked in recent years. Research led by Dan Kahan, a law and communication expert at Yale Law School, suggests that scientific knowledge isn’t as important as conforming to cultural values, or what he calls “cultural cognition.”

Cultural cognition is likely at play with fake news, too. People who share untrue stories may identify strongly with a partisan position or narrative—the fake news reflects how they see both themselves and the world. When someone shares a piece of political fake news, it is an act of confirmation bias, an attempt to buttress their existing point of view.

In this context, fact-checking a statement on social media “goes to the core of someone’s identity,” says Mike Ananny, a media scholar at the University of Southern California. “You’re not just asking them to accept the veracity of some piece of data or some statement. You’re kind of asking them to change how they see themselves as a person. And that’s a different hurdle.”

When it comes to politics, we “take a personal stake,” says Alice Marwick, a fellow at the Data and Society Research Institute who studies how people present themselves and interact on social media. Political fights on social media are “not an objective debate … but a set of heated emotional arguments that get to the very core of what people believe and how they see their place in the political process and the future of the United States.”

“When people are engaging at that level, they are not interested in hearing counterpoints,” Marwick adds. “And that goes just as much for people on the left side of the spectrum as for people on the right.”

The websites that peddle fake news have tapped into this sense of identity, whether intentionally or not, by using dramatic headlines and inflammatory language that appeal to emotions. According to Rosanna Guadagno, a social psychologist at the University of Texas at Dallas who studies online persuasion, posts go viral when they make people angry, disgusted, or alarmed.

Engage First with the Person, Not the Content

So if fake news—particularly political fake news—is more about personal identity than facts, then pushing back may require appealing to identity. This means thinking about who that person is, as well as their relationship to you. “If it’s someone who you care about, remember that you cannot engage with the content of what’s being presented,” says Dannagal Young, a communications scholar at the University of Delaware who studies satire and political media effects. “Which seems totally irrational, and in some ways it is. What you need to do is engage with the human first.”

“Empathy, perspective taking—doing outreach that connects with the person and not the topic,” Young adds. It works, she says, and “it is wonderful.”

Try to figure out why a friend is sharing a particular piece of fake news—what narrative does it support in their overall worldview?

One way to do this is to “meet people halfway with respect to the values and identities they have,” says Daniel Kreiss, a political communications scholar at the University of North Carolina.

In other words, try to figure out why they are sharing a particular piece of fake news—what narrative does it support in their overall worldview? For example, if a friend shares misinformation about the safety of vaccines, they are likely doing so because they are worried about the health of their children. Even if the science on vaccines shows the opposite of what the post says, the poster’s “underlying message is I’m a good parent,” says Emily Thorson, a political scientist at Boston College. “Affirm what they want [you] to affirm”—that they care about their kids—“and let that be true, along with the fact being wrong.”

Countering fake news may be especially effective when it comes from someone with a similar political identity, says Kreiss, because it is less threatening. If you lean left and you see your Bernie-loving aunt post fake news from Occupy Democrats, for example, or if you’re a conservative whose college roommate regularly likes the Infowars page, you might highlight your shared values before pointing out that the sources don’t have great track records when it comes to facts. Better yet, provide a credible media outlet that you know will appeal, Kreiss adds, particularly if you can link to a specific story at that outlet that debunks the fake news.

It may also help to put the argument in context, says Ananny. For example, one way to do this might be by reminding them of your existing relationship as family members or friends, and of the values and experiences you share. This is an approach Whitlock has used in her own attempts to engage with friends on Facebook. “They know me. These are people I went to school with. We struggled through the junior research paper that was 30 pages long, and we all learned to think critically from the same teachers in the same classroom in the same year,” she says. “I know they know better.”

Finally, keep in mind that fights on social media are public—which can often make them more of a performance than a heartfelt interaction. It might be best just to say, “Hey, let’s take this conversation to a private message,” or even offline.

“People don’t like to be proven wrong in a public environment, and Facebook is public,” says Guadagno. “If you’re going to challenge someone, be sure they are okay with arguing publicly. Otherwise, take it off that space to talk.”

Changing Hearts and Minds: Not So Easy

Whether any of these tactics will actually work is unclear. As Brendan Nyhan, a political scientist at Dartmouth College, says, “partisanship is a hell of a drug.” And personal political identity is especially addictive.

To make it even harder, misinformation seems to stick in people’s minds, making it hard to correct in any permanent way. According to new research by Briony Swire, a PhD candidate in cognitive psychology at the University of Western Australia, corrections on social media can in fact change people’s minds about a bit of fake news. But it doesn’t last. “In our lab, we’ve started calling it the expiration date of corrections,” Swire says. “It’s really interesting, actually, that people are really willing to say Okay, that’s true, this is false. And then if you test a few weeks later, they’ve definitely started to regress.”

When I followed up with Halama and Miller around two months after their initial Facebook fight, they were back to debating over fake news on social media.

Still, Miller hopes the social media conversations are worth it. “There are lots of other people [among] our Facebook friends who might be interested in the conversation,” he says. “There may be people who think like he does, and maybe I could reach them by talking to him.”

Human minds and habits are incredibly hard to change. Still, that doesn’t mean trying to combat misinformation in one’s social media feeds—or in “real life”—is always futile.

“I think the interaction helped me to have a healthy dialogue without fighting—talking to each other instead of arguing and being enemies,” says Halama. “So I don’t regret it at all.”

But did the interaction change what Halama considers fake news, or make him question the sorts of stories he shares online?

“None of it changed, no,” he says. “Not at all.”

For journalists committed to facts and reason, that’s a bleak reality. Human minds and habits are incredibly hard to change. Still, that doesn’t mean trying to combat misinformation in one’s social media feeds—or in “real life”—is always futile. Whitlock says she’s tried to do so many times. Her efforts don’t always go anywhere. But she’s seen some small successes that fuel her determination to keep fighting the good fight. “I’m very happy to say that two of my friends from high school who had been sharing [Infowars links] on their pages no longer share it,” says Whitlock. “And some of my friends who share Occupy Democrats no longer share that source.”

So, should you try to enter the fray of the Facebook fake-news fights? And if you do, will it make any difference? The answer is: It depends. But if you do try to change hearts and minds on social media, come with your facts, but also your empathy.

Brooke Borel is an independent journalist and author. She has written for The Atlantic, the Guardian, FiveThirtyEight, BuzzFeed News, Audubon, Popular Science, The Verge, and PBS’s Nova Next, among others, and her work has received support from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the Alicia Patterson Foundation. She teaches writing workshops at the Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute at New York University and the Brooklyn Brainery. Her books are Infested: How the Bed Bug Infiltrated Our Bedrooms and Took Over the World and The Chicago Guide to Fact-Checking. Follow her on Twitter @brookeborel.