Most every freelancer has gotten stuck with a low-paying assignment or two (or, let’s be real—probably more than a few). While poor pay is often an unavoidable part of freelancing, low pay rates aren’t just damaging to freelancers’ bank accounts. They also threaten journalists’ ability to do high-quality work. “Good reporting just takes time,” says independent journalist Wudan Yan. “It’s an investment on everyone’s part, and I think editors and publications should take that seriously.”

When freelancers are offered a plum assignment marred by a low pay rate, they face the (sometimes painful) decision of whether to take the assignment anyway, turn it down, or ask for more.

For many, mustering up the courage to ask for a higher rate is a struggle. Some freelancers may have little knowledge of what constitutes fair pay and whether asking for more is a smart business move or a sure ticket to unemployment. “Part of the problem [with] low rates is that people aren’t talking about them enough and creating enough noise,” Yan says. Some freelancers, she believes, are “just accepting what’s happening [and] not asking for more because we don’t know how much is reasonable to ask for.”

How often do freelance science journalists ask for higher pay—and do editors view such requests as improper or irritating? Does asking for more money actually pay off? To find out, we surveyed 267 freelance writers and 49 editors—and interviewed several others—working in science, health, and/or environmental journalism about the practice of asking for higher rates. Our results show that despite what many freelancers fear, it rarely hurts to ask for more money when offered an assignment. Some editors say they expect these requests, and our data show that asking for more money can often pay off. Honing negotiation skills is both a vital part of building a successful freelance career and an important step toward safeguarding the quality of science journalism.

The key, according to the freelancers and editors we surveyed, is to ask in the right way: Be concise, straightforward, and polite. Consider whether what you’re asking is in keeping with your experience and with your relationship with the editor or publication you’re dealing with. And be ready to act on the answer—either by delivering good, clean copy to justify your hike in pay or deciding whether to walk away from a rate that’s just too low.

Asking Rarely Hurts and Often Helps

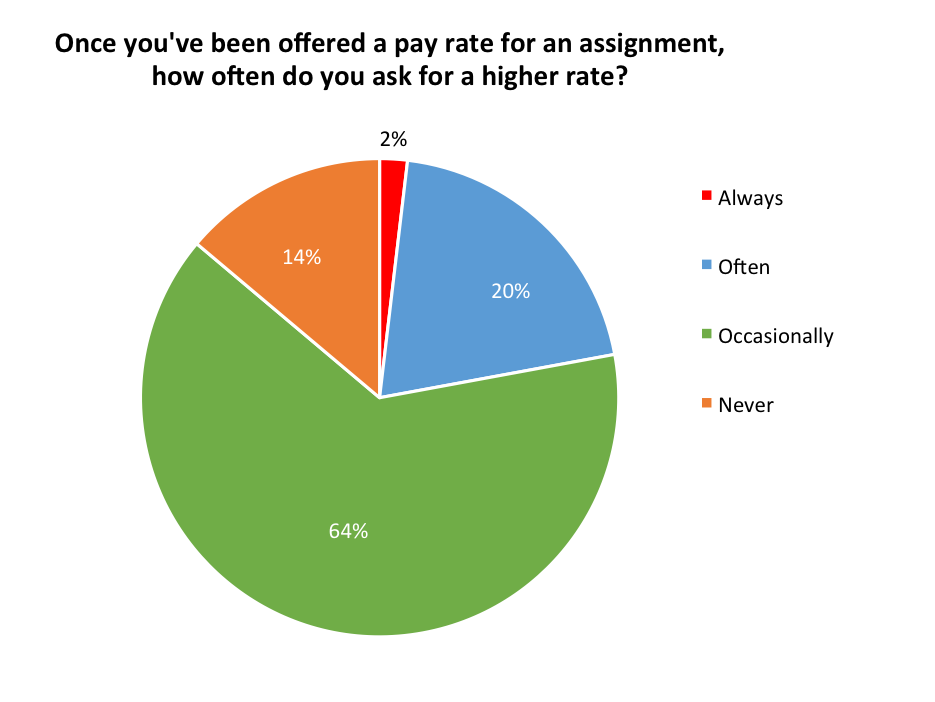

Some freelancers say asking for more isn’t worth the awkwardness or risk of retribution. Among those we surveyed, 14 percent said they never ask for a higher rate. Some said they’re just starting out in the field and are willing to work for whatever they’re offered, or that they feel what they’re being paid is satisfactory. Others indicated that they assume their editor is offering the best rate they can, so they don’t bother asking for more. And still others cited fears of losing an assignment or harming relationships with editors. For example, one respondent feared being “rejected and then branded as someone who asks for more money.” Another worried about burning bridges with clients.

But this hesitation may be mostly unwarranted. In fact, freelancers should ask for higher rates more often than they do, says Kendall Powell, a longtime freelance science writer and co-chair of the National Association of Science Writers’ Freelance Committee. (Here, she is not speaking on behalf of NASW.) “You shouldn’t just take what they offer unless it’s incredibly good,” says Powell, who also teaches about the ins and outs of contracts at the University of California Santa Cruz Science Communication Program. As with any job offer, she says, you have the freedom to negotiate.

Among freelancers we surveyed, 84 percent reported that they ask for higher pay rates occasionally (64 percent) or often (20 percent). Some said they make an effort to counter low rates with an ask for more, noting that doing so is a matter of valuing their work. For instance, one respondent said, “I’m confident in my worth and experience, so even if it’s a highly desired publication I always try to ask for at least a little more.”

And asking doesn’t seem to hurt, by and large. Many respondents said their requests are typically well-received: Editors rarely get upset, and they are often accommodating. One freelancer observed, “In my experience, many editors want to pay more if they’re able, because they want to treat writers well.”

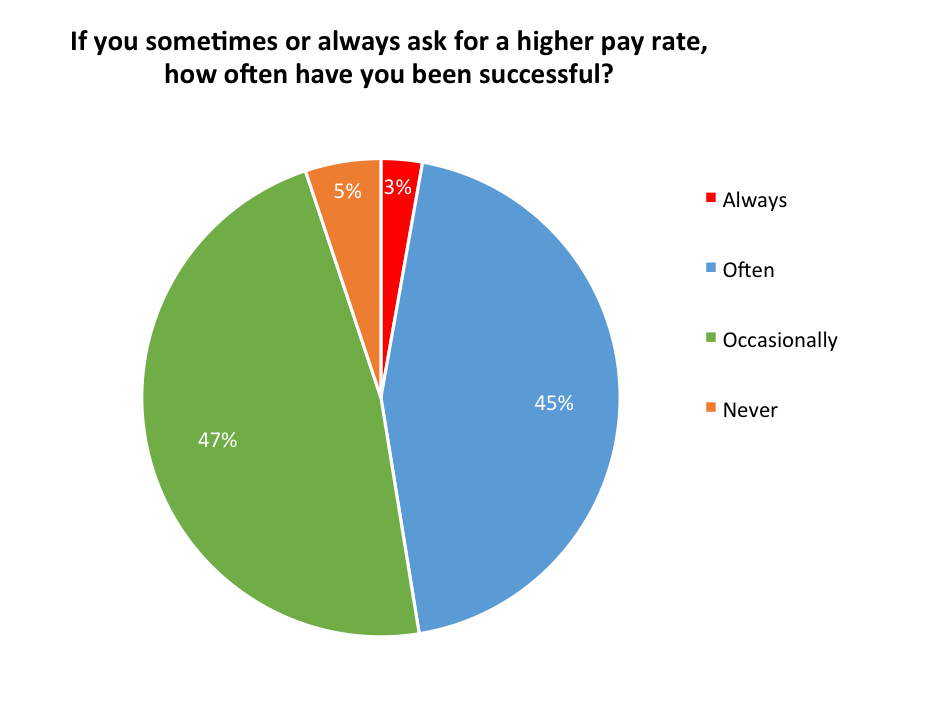

Our data support these comments: Of freelancers who ask for higher rates, almost all—95 percent—said their requests are successful at least occasionally. And the more often freelancers ask for higher rates, our results show, the more often they actually get them1.

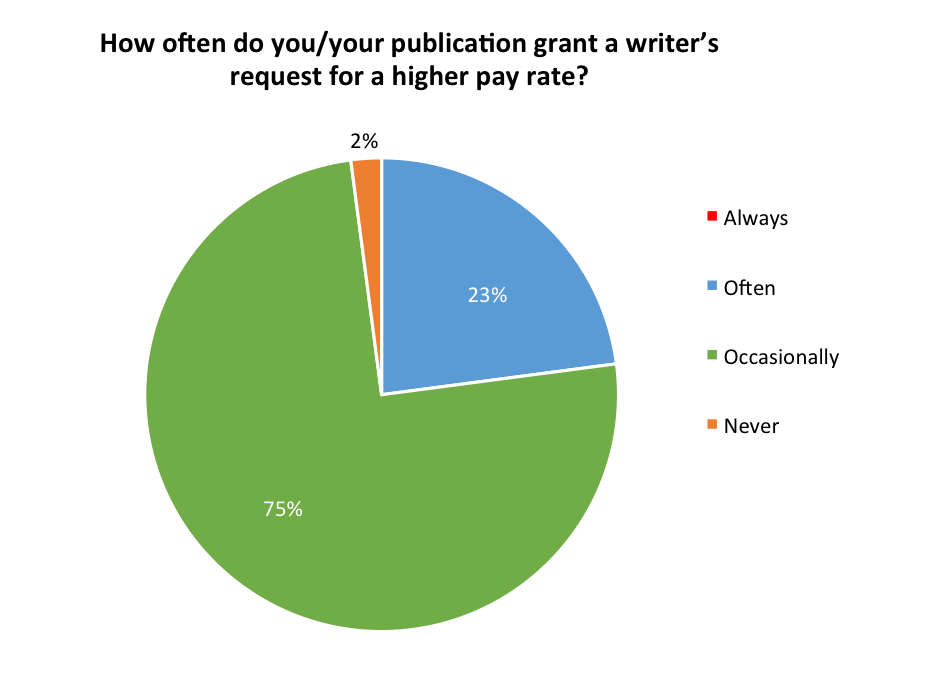

Furthermore, 75 percent of the editors we surveyed said they occasionally raise rates when asked, and 23 percent said they do so often.

There seems to be a relatively small risk that asking for more money will cause a client to retract an assignment offer, according to our results. Only six of the 49 editors (12 percent) we surveyed said they’ve ever revoked an assignment because a freelancer asked about increasing the rate. (Furthermore, some editors’ follow-up responses suggest that the more common occurrence is a mutual decision to drop the assignment.)

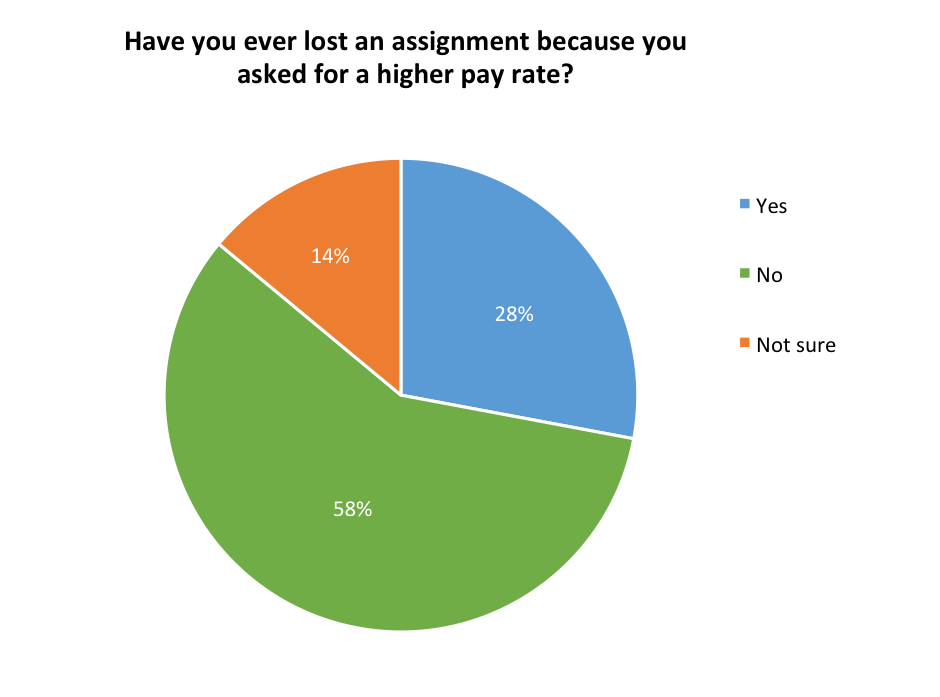

That said, 28 percent of freelancers said they had lost an assignment because they asked for higher pay, and 14 percent said they weren’t sure. Fifty-eight percent said they had never lost an assignment because they asked for higher pay. (Even within the first two groups, though, 88 percent said that when they ask for higher pay, they are occasionally or often successful; perhaps it’s not surprising, then, that they continue to do so.)

Negotiating Is Normal

Asking for more money tends to pay off, and few editors will fault you for doing so, our data suggest. The vast majority of those we surveyed—90 percent—said they believe it’s reasonable for freelancers to negotiate.

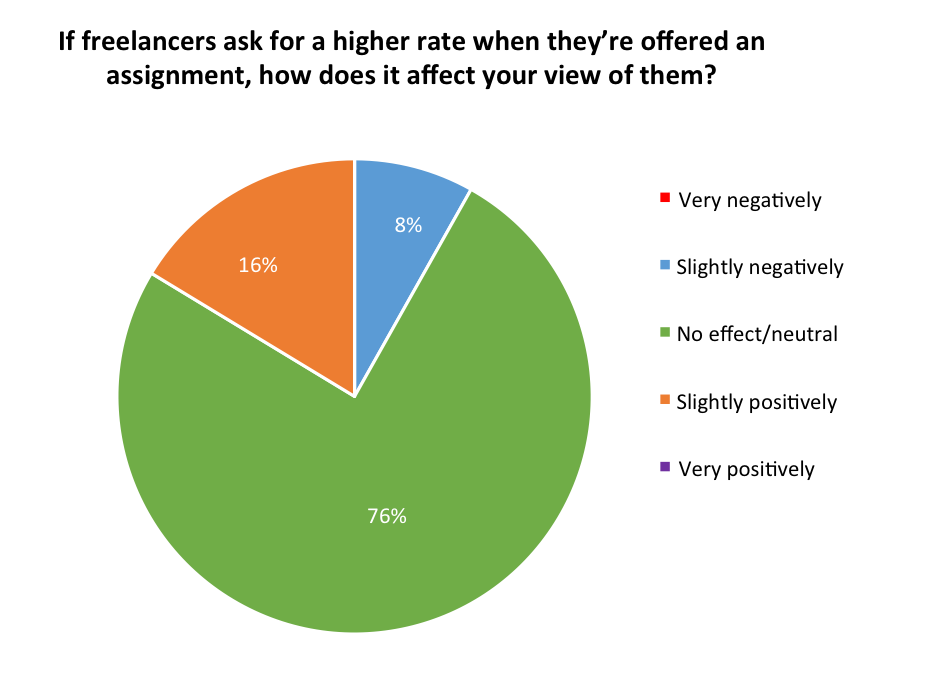

And 76 percent reported that being asked to consider paying a higher rate doesn’t impact how they view a writer. Only four of 49 editors we surveyed (8 percent) said such a request affects their view of the freelancer slightly negatively, and none said such requests have a very negative effect.

In fact, some editors even welcome a request for higher pay—provided it’s made in a professional way. Sixteen percent of the editors reported that being approached about a raise slightly boosts their view of a freelancer. One editor said these requests demonstrate ambition. And, says freelance journalist and editor Kat McGowan, asking for higher rates also shows that a freelancer has a good sense of what it will take financially to do a story well. Negotiating for better pay, she says, “can be a good part of building your relationship with an editor. It doesn’t have to be a hostile or adversarial conversation.”

Discussing pay rates is a natural part of the assigning process, agrees NPR science desk editor Scott Hensley. Being asked about a possible raise doesn’t offend him, he says. “I’m not judging the person based on their negotiating skills about the pay,” he says. Instead, Hensley says, he focuses on the quality of a freelancers’ story ideas and their track record of doing similar work.

Many of the freelancers we surveyed also said that asking for higher rates is just part of the job. It’s business, not personal. Writers who approach freelance writing in this way—as a small business rather than as an art—may negotiate with more confidence, Yan says. “Recognizing that you’re a business means that negotiating is not supposed to be something scary,” she says. “That’s how you sustain yourself as a business.”

Finding Opportune Moments

Several survey respondents who reported being new to science writing said they felt they should wait until they’re more established before going after higher rates. Our data follow this pattern: We found a significant relationship between the writers’ experience levels and how often they ask for more money2. Freelancers with just one to five years of experience more commonly reported that they never ask for higher rates, compared with those who have more experience.

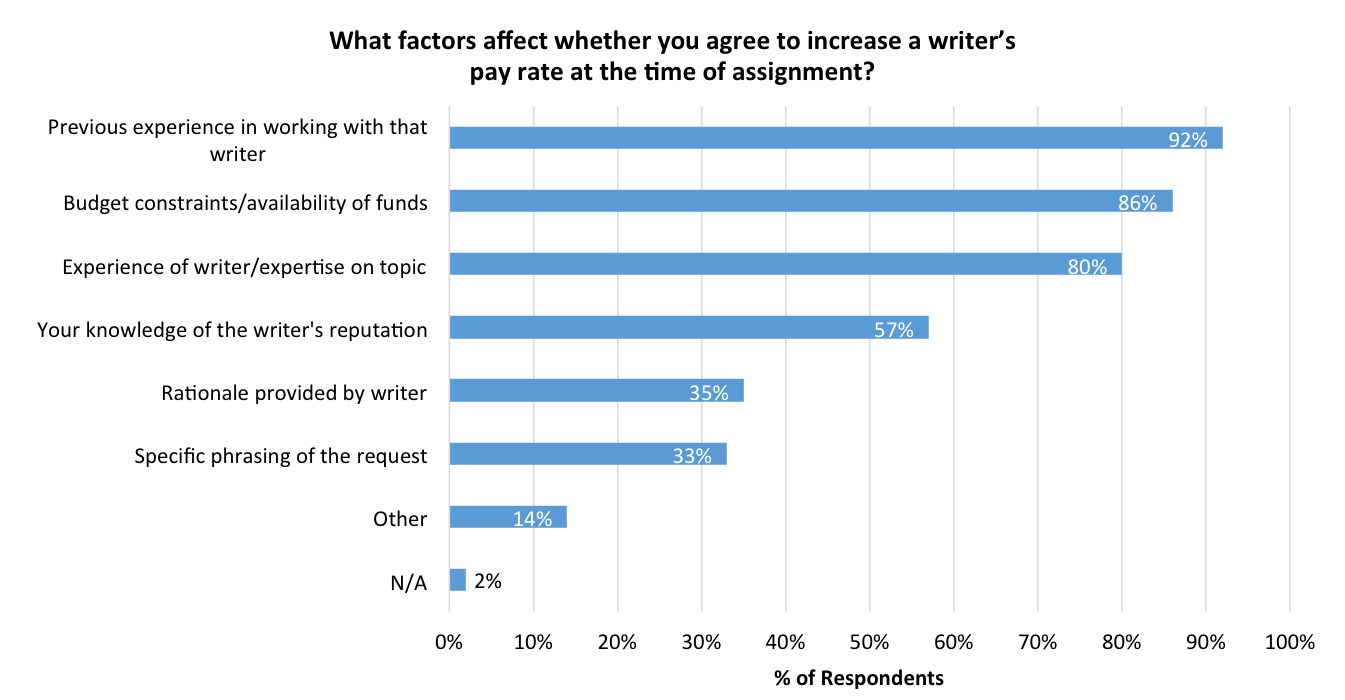

This tendency may represent a realistic view of the marketplace. Forty-seven percent of surveyed editors said that a writer’s experience or expertise determines what rate they offer in the first place—and 80 percent said this factor affects whether they’ll grant a request for more money. High Country News senior editor Jodi Peterson says she also considers the quality of a freelancer’s clips. “If they’re really a writer with some chops, then we’ll acknowledge that by paying them a higher rate,” she says.

That said, our results hint at a discrepancy in the outcomes reported by editors and freelancers: There wasn’t a significant relationship between freelancers’ experience levels and how often they said they actually obtain higher pay rates3.

In addition to adjusting rates according to experience, Peterson says she’s most likely to consider a request for a bump in pay if it comes from someone she’s worked with before. In fact, 92 percent of surveyed editors said their previous experience in working with a writer affects whether they’ll increase a rate. (The second most cited factor, reported by 86 percent of editors, was an obvious one: budget constraints. Note: Editors could choose more than one factor in response to this question.)

Building a good rapport with editors over time serves as a foundation for asking for higher rates, says freelance journalist Zach Zorich. “If you can over-deliver on people’s expectations—if the editor feels like the work they’re getting from you is worth more than what they’re paying you—that’s really the ideal situation,” he says.

In keeping with that idea, many freelancers we surveyed said they prefer to ask for an overall raise in rates once they’ve worked for a publication for a while, rather than jumping into negotiations early on. Powell suggests that when editors start coming to you with assignments, that’s usually a good time to ask for a raise. Another opportune moment is right after you finish a particularly extensive project. “Ride that wave of the fact that they liked something you just did, and they know that it took a lot of work,” she says.

In other cases, the circumstances of a particular assignment may justify a hike in pay. For example, if an editor requests an unusually quick turnaround, it’s standard practice to ask for more money, Powell says. In addition, several surveyed freelancers said they ask for extra funds for elements that accompany a story, such as art or sidebars.

Also, if a particularly challenging assignment comes up, consider the time extra reporting will require and negotiate the pay rate accordingly. “If you’re rushing through it because you have to do a bunch of other work that is more lucrative, the work is going to suffer,” McGowan says. That said, if a story ends up taking more work than anticipated—and thus perhaps deserves more compensation—surveyed editors said it’s crucial to communicate this well before the deadline.

Judging Your Worth

When you do ask for more, how high should you aim? Finding the sweet spot for negotiations—while avoiding asking for something exorbitant—is key, says Powell. “People should be paid what they’re worth,” she says. “There’s no hard formula for what that is—you kind of figure it out on your own.”

Many writers establish a target rate for negotiations. The most common factor used to decide whether to ask for more money—cited by 72 percent of freelancers we surveyed—is how the offered rate compares to their usual rate. (And 51 percent of freelancers said they mention this typical rate when they ask editors to consider a higher rate.)

Another way to gauge how much to negotiate for is to estimate the hourly rate for the assignment—something that 42 percent of freelancers we surveyed said they do when deciding whether to ask for more.

To get a sense of the average rates offered by different types of clients, from trade publications to national magazines, members of NASW can check the rates tables produced by the organization’s 2014 Science Writers Compensation Survey. (The survey asked NASW members about their compensation in 2011 and 2012.) These tables provide medians and ranges of rates writers were paid, broken down by dollars per word and per hour.

One of the best ways to get insider information about individual publications’ rates is to ask other freelancers who write for similar markets, says Powell. Journalists can also check databases like NASW’s Words’ Worth (available only to members) or Who Pays Writers? for publication-specific pay rates.

Making the Ask

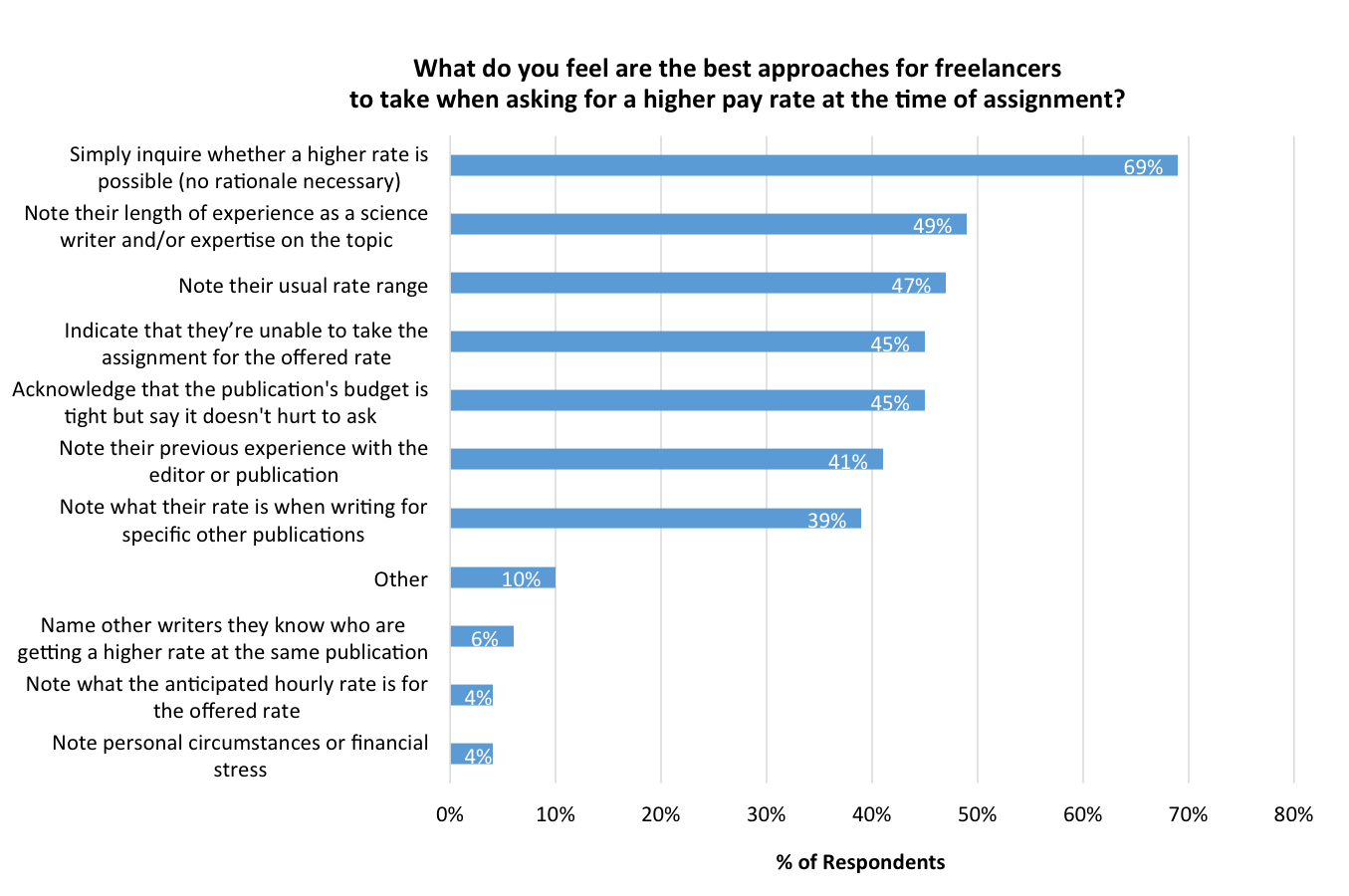

Once you know when to ask, and for how much, making the request itself should be fairly straightforward. Most editors and freelancers who responded to our surveys said that the best approach is to simply inquire whether a higher rate is possible. “I don’t really need like a huge, elaborate justification,” says Peterson.

If freelancers feel compelled to provide some rationale for their request, a small amount may work in their favor, says Zorich, who is also a contributing editor at Archaeology magazine, where he was previously involved in assigning stories and negotiating pay rates with freelancers. “Keep in mind that when you’re asking your editor for a higher rate, what you’re really asking is for that editor to go to the editor-in-chief and make the argument that you deserve to be paid more,” he says. Provide a few helpful points, such as how problem-free your previous stories have been or the attention they’ve drawn on social media. Don’t be afraid to toot your own horn a little bit, Zorich says. “Modesty is not going to help you.”

Another rationale freelancers can consider including in a request, according to 39 percent of the surveyed editors, is the rates they receive from specific other publications, such as a publication’s direct competitors. But writers should tread lightly here, as other editors say this tactic turns them off. “[Mentioning other publications’ rates] doesn’t really matter to me very much, because we’re not able to be that competitive,” says Peterson, who notes that her budget at High Country News is limited but she can sometimes manage a fairly small bump in pay.

Moving Forward

In the end, journalists who ask for an increase in pay should be prepared for the outcome—whether it’s a raise or a rejection. Back up an increased rate with quality work, editors say. The “nightmare” scenario for an editor, Zorich says, would be if he or she raises a writer’s rate but the next article they file is in terrible shape. “You haven’t justified the faith that editor is showing in you,” he says.

And if your request is declined, there’s probably no point in pushing back, says Zorich. Journalists should keep in mind that editors often have to defer to others, such as publishers, when it comes to allocating their funds. And budgets can be ridiculously tight. For example, when Zorich was editing for a different magazine, he says he was once told that if he wanted to bump up one writer’s rate by a certain amount, he’d have to pay another writer that much less on a different story.

That said, several editors we surveyed said freelancers should recognize that a “no” now doesn’t mean they can’t ask to revisit their rate in the future. As one editor commented, “If I can’t say yes when you ask, you’ve still planted the seed in my mind. I might say yes a few weeks or months later, when budgets have eased up.”

When editors reach the limit of what they can offer, it’s up to the writer to decide whether they want to walk away, Peterson says. Eighteen percent of freelancers we surveyed said they typically turn an assignment down if their request for more pay is declined, while 40 percent said they usually do the story anyway. About 31 percent said their decision depends on several factors, such as their current workload, how invested they are in the story, or how badly they want a clip from a particular outlet.

It may make sense to make occasional exceptions for a job you really want. But as Powell cautions, habitually accepting subpar rates may come at a greater cost. “Every time you take a low rate for a not-good reason—just because it’s what was offered to you—you’re undermining the ability of everyone else to make a decent living,” she says. Powell says it’s up to freelancers to push back collectively against unfair rates (and unethical pay practices), so they don’t stay low or drop even further. Organizing in this way, she notes, has led to real progress before, such as in January’s agreement between the National Writers Union and Nautilus magazine to resolve (what was ultimately) 24 freelancers’ overdue payments. Many outlets depend on a stable of freelancers that they can’t afford to lose altogether, Powell says. “As freelancers, our power lies in our numbers.”

Statistical Analyses:

- Significant: Relationship between asking frequency and success frequency [Χ2(3, N = 210) = 16.29, p < .01] Note: Freelancers who reported always asking for more money were excluded from analyses due to a small sample size (N = 5).

- Significant: Relationship between experience level and asking frequency [Χ 2(6, N = 262) = 16.85, p = .01*] Note: Freelancers who have been freelancing for less than a year were excluded from these analyses due to a small sample size (N = 5). *This result did not survive correction for multiple comparisons.

- Not significant: Relationship between experience level and success frequency [Χ 2(6, N = 213) = 4.59, p = .60] Note: Freelancers who have been freelancing for less than a year were excluded from these analyses due to a small sample size (N = 2).

- Not significant: Gender difference in asking frequency [Χ 2(2, N = 259) = 2.24, p = .33] Note: Freelancers who reported always asking for more money were excluded from analyses due to a small sample size (N = 5).

- Not significant: Gender difference in success frequency [Χ 2(3, N = 212) = 2.78, p = .43]

Special thanks to Briana Kille for consultation on statistical analyses. Any errors remain the responsibility of The Open Notebook.

Rachel Zamzow is a TON fellow sponsored by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. She is a freelance science writer based in Waco, Texas. The brain is what makes her tick, so most of her stories have a psychology or neuroscience slant. But she’s always interested in anything new and exciting science has to offer. She’s written for a variety of publications, including the award-winning autism research news site Spectrum and The Philadelphia Inquirer, where she was a 2014 AAAS Mass Media Fellow. She tweets @RachelZamzow.