The story diagrams—or Storygrams—we present on these pages annotate stories to shed light on what makes some of the best science writing so outstanding. The Storygram series is a joint project of The Open Notebook and the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing. It is supported in part by a grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. This Storygram is co-published at the CASW Showcase.

It’s a bad time to be a North Atlantic right whale. This spring, these critically endangered animals started rapidly dying—one right after the other, with six dead in just one month.

In fact, the whales were dying so quickly that when Ed Yong, a staff writer at The Atlantic, reported the alarming trend in a news story, he needed to revise the text within hours of publishing.

“Regretfully, I’ve had to update this story. In the hours since writing this, a SIXTH dead North Atlantic right whale was spotted on a surveillance flight today,” Yong reported on Twitter. “This is truly crushing. I feel for the people on the frontlines.”

It can be difficult to pull off doom-and-gloom conservation stories, especially those involving charismatic megafauna—after all, readers can only engage with so much despair, and who knows if anyone actually cares?

But starting with the first, evocative paragraph, Yong weaves humanity and compassion into what could have been a staid regurgitation of whale facts and grim statistics. As Yong writes, it’s not exactly clear why so many right whales are suddenly dying—but it is clear that they are dying in terrible ways. And rather than shying away from the gruesome, unnerving details, Yong walks the reader through that reality without crossing into cheap shock-value territory.

Throughout the story, his sensitivity to both humans and animals makes the right whales’ plight tangible—these animals aren’t just numbers!—and he aptly describes the complex ways in which humans are trying to reduce preventable whale deaths. Yong is a skilled storyteller and it shows, especially in his pacing and characterizations.

“I write these pieces in the hope that they’ll make a tiny dent in moving our collective consciousness towards valuing wildlife,” he says, during a Q&A following the annotated story. “Maybe that’ll help. Maybe it won’t. But if the North Atlantic right whale goes extinct, it damn well won’t do so silently.”

Story Annotation

“North Atlantic Right Whales Are Dying in Horrific Ways”

Six individuals—more than 1 percent of the population—were found dead just this month, the latest entries in a troubling pattern.

By Ed Yong, The Atlantic

Published June 27, 2019

(Reprinted with permission)

She was called Punctuation, after the small scars on her head that looked like commas and dashes. She was a North Atlantic right whale, one of an estimated 411 left in the world. She was one of just 100 reproductively active females left. She was mother to at least eight calves, and a grandmother to at least two grand-calves. She was about 40 years old when her body was found floating in the Gulf of St. Lawrence on June 20, 2019. Preliminary results from a necropsy suggest that she likely died after being hit by a ship.This lede is beautifully done. It introduces a whale and makes her more than just a random animal: She has a name, she has a family, she’s one of very few left, and now she’s dead. Yong’s use of anaphora here—the repeated “she was”—catapults the reader into the story while immediately building tension. You know something bad is coming, given the past tense, and the final twist in this graf—“she was about 40 years old when her body was found”—lands with a painful wallop.

It had been a galling month for the many people who care about North Atlantic right whales. Wolverine, a 9-year-old male named after the three propeller scars on his tail,The details Yong includes here help to make the whales more than mere statistics—they’re individuals who were known—and they also shine a light onto the people who watched the whales for long enough to know them and name them and care about them. was found dead in the same waters on June 4. The body of Comet, a 34-year-old grandfather named after the long scar on his flank, was discovered dead on Tuesday night, alongside an unnamed 11-year-old female, who was just about to become sexually mature.Oof. What a masterful way to introduce the devastating fact that it takes more than a decade for these whales to reach reproductive maturity. A fifth whale, an unnamed 16-year-old female found near Anticosti Island, in Quebec, was confirmed dead yesterday. A sixth was spotted off the Gaspé Peninsula, also in Quebec, on a surveillance flight today. That’s more than 1 percent of the estimated total population, dead in less than a month.This sentence, and the elements of time throughout this graf, are telling readers why they are reading this story now.

“Honestly, I don’t have the words,”This opening quote packs such a punch: It says it all without saying anything. When your experts are speechless, you know you’re dealing with something dire. says Regina Asmutis-Silvia, executive director of Whale and Dolphin Conservation North America, who has studied these animals since 1990.Here, Yong is establishing his source as an expert by offering a glimpse into her credentials, and setting up her ability to provide longitudinal insights. “It’s devastating. There’s now more people working on right whales than there are right whales left.”

How much death can a species tolerate?When used well, rhetorical questions can organically propel the story; this one works because it sets up the crux of the problem using powerful language and is positioned in the exact place where readers might be asking themselves that same question. “Tolerate” is a great word to use—it’s clinically removed yet carries an emotional connotation, and it makes me wonder: Is death a thing to be … tolerated? How much death can anyone tolerate, let alone a whole species? It signals the magnitude of the problem without making it overly sentimental. Researchers have estimated the number of North Atlantic right whales that could be killed every year while still maintaining a stable population. “That number is 0.9,” says Sarah Sharp, from the International Fund for Animal Welfare. Six have died this month alone.Ouch. The simple, short phrasing here acts like a rhythmic stop sign and sets this sentence apart. It’s kind of the equivalent of a record-scratch. “The species cannot sustain these kinds of losses. We’re seriously worried that extinction is in the all-too-near future.”

Aside from Punctuation, it’s still unclear why the other five whales died. Wolverine’s necropsy was inconclusive, and the other four have yet to be examined. Natural causes are unlikely: None of these individuals were anywhere close to the species’ estimated life span of 80 to 100 years.Again, a masterful way to introduce fundamental facts about right whale biology without just doing a fact-dump. And just last week, Sharp and her colleagues published a paper that analyzed the deaths of 70 North Atlantic right whales since 2003. In the 43 cases where the team could determine a cause of death, 38 were due to just two causes—ship strikes, and entanglements.This graf is building on the story’s introduction and outlining the mysteries, horrors, and science that will carry it to its conclusion. The only element I wish were briefly mentioned in this section is the complex regulatory situation that’s evolving to help keep these whales safe; at this point I was deep into the pit of despair and was wondering if people with the power to alter the whales’ plight cared enough to make a difference.

Of Punctuation’s two known grandchildren, one was killed by a fishing line in 2000, and the other was last seen in 2011 with deep propeller cuts in his back. Another of her calves was killed by a ship in 2016. She herself had survived five separate entanglements and two ship strikes, before one more ended her life.Ugh, this sentence is devastating. It wraps Punctuation’s entire history into the tragedy that ignited this story, making it clear that these whales are suffering A LOT. And just when you thought it couldn’t get worse … wait for the next graf.

Ship strikes. Entanglements.Again, the pacing here is phenomenal. These simple words mirror the bluntness of what Yong is about to describe, and they act as stop signs, signaling that it’s time to slow down and pay attention. There is something almost euphemistic about these termsHere, Yong is stepping back from the numbers and offering a comment about what is happening to these whales and how that gets discussed. When journalists have enough expertise to offer an analysis of information, rather than just reporting it, it adds immense value to a story. that belies the horror of the wounds they inflict. Six of the whales Sharp studied had their skulls fractured by incoming ships. Three had their spines broken. Six were lacerated by propellers. One calf had its entire tail amputated. One whale survived her run-in with a propeller, but 14 years later, when she was pregnant, the presence of the fetus caused her scars to split, leading to a fatal infection.This whole paragraph is heartbreaking and gives just the right amount of brutal reality. Not skimming over the details, but not diving too deeply into them.

If you’re enjoying this Storygram, also check out two resources that partly inspired this project: the Nieman Storyboard‘s Annotation Tuesday! series and Holly Stocking’s The New York Times Reader: Science & Technology.

Entanglements are no better. Over time, ropes slowly eat into flippers, tails, heads, and even the baleen plates inside the whales’ mouths. In one case, a line lacerated a whale’s blowhole, likely affecting its breathing or preventing it from keeping water out while it dove. Some of these deaths are painful. Others are painful and long.That is a wrenching distinction. “This isn’t just a conservation issue. It’s an animal-welfare issue,” Sharp says. “Whales are out of sight, out of mind, and people aren’t seeing them suffer. It’s not a cat or dog walking down the street with these horrible injuries. But it’s important for people to understand how bad this is.”Here, Yong is letting his expert offer an observation about why it’s tricky to make tangible, beneficial changes for the whales. It’s the kind of insight he could have offered on his own, yet it carries more weight coming from Sharp.

Slow, docile, and full of oily blubber, North Atlantic right whales made great targets for whalers, who hunted them to near-extinction by the early 20th century. After hunting was banned in 1937, the population stabilized, but never truly recovered. After a brief uptick, the whale population has started to decline again since 2010, perhaps because the whales have changed their behavior.This graf is providing some historical context while answering the questions readers are probably asking at this point: Why aren’t there more right whales? Didn’t I just hear something about the population somewhat recovering?

The whales used to regularly visit Cape Cod Bay in the early spring, before migrating up the Eastern Seaboard to the Bay of Fundy. Their consistent movements made it easier for regulators to protect them, by controlling shipping lanes or forcing fisheries to close at certain times.A simple, clear way of introducing the main regulatory prongs that will be addressed in the coming grafs. But in recent years, warming temperatures have depleted their food sources, forcing them to head further north into dangerous waters where they enjoy no protections.Ah, so there is a climate change angle. In other words, humans are dealing blow after blow after blow to this population.

An unprecedented 17 individuals died in 2017, and only five calves were born. Last year brought three more deaths, and no calves—a deeply worrying trend. But this winter, seven new calves were seen. “It felt like we could breathe for a minute, like maybe things were going to turn around,” Asmutis-Silvia says. But the events of recent weeks have largely quenched that hope. “The absolute hardest part of all this is that these deaths are preventable.”

About a decade ago, the U.S. instigated a 10-knot speed limit in places where (and at times when) the whales are seen—a measure that led to fewer collisions and less severe injuries.I’m curious about the source of this information, mostly because I really want it to be that simple—not easy, but simple—to prevent fatal ship strikes. When the whales started moving into Canadian waters, Transport Canada initially tried to set up more dynamic restrictions, based on sightings from planes.This type of dynamic mitigation strategy sounds so complex and tricky to communicate and implement, and crucially, Yong is not glossing over the difficulty involved. After the fifth body was found, it immediately implemented a stricter 10-knot limit for vessels of 65 feet (20 meters) or longer in two shipping lanes in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. That ban will be enforced by increased monitoring, and offenses will be subject to a $25,000 fine. “It’s been a hard lesson to learn,” Asmutis-Silvia says.

Preventing entanglements is harder, she adds. The main threat comes from the vertical ropes that connect lobster and snow crab traps on the seafloor to floating buoys on the surface. Earlier this year, the Canadian government banned lobster and crab fishing in a “static zone” where most right whales were seen last year, and was ready to set temporary bans in a wider “dynamic zone” if any individual was seen. But some of this year’s five dead individuals were found outside these areas.Ouch.

Speaking at a press conference today,Here, Yong is identifying where he got this information from, which is important for readers in case they want to track it down. Adam Burns of Fisheries and Oceans Canada said that the snow crab fishery in the Gulf of St. Lawrence will close this Sunday, and the use of fixed gear will decrease significantly. In the long term, several companies and research groups are working on “ropeless gear” that could, for example, allow fisheries to summon lines to the surface only when they are fishing. “That would solve 90 percent of the entanglement problem,” Asmutis-Silvia says.Fingers crossed. C’mon, humans.

Matthew Hardy of Fisheries and Oceans Canada added that the agency is continuing its intense surveillance work to find out where exactly the whales are. So far, an estimated third of the world’s population has been seen in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, but their exact whereabouts seem to shift from year to year. That worries Asmutis-Silvia. “Where are the others?” she asks. “We might be looking at a raging fire in Canada, but I’m concerned about where we don’t know there’s a problem.”

“I wouldn’t say it’s unusual to not know where a lot of them are,” Sharp says, “and hopefully it means they’re far offshore and not near shipping lanes and fishing gear. But we do need to know where they are to implement proper protection.”These last quotes are again driving home just how difficult it is to set up meaningful regulations. At best, the shipping industry is going to grump about slowing down or being told where to go (all of that decreases efficiency and carries a cost), and fisheries don’t appreciate being told what kind of gear to use (again, there’s a cost to updating equipment and losing fishing space). Throw in substantial uncertainty about where the whales actually are and the picture becomes almost impossibly murky—yet no less dire.

A Conversation with Ed Yong

Nadia Drake: This story reads so seamlessly, propelling readers from the initial sobering reality and unavoidably distressing statistics to the historical reasons for the demise of the North Atlantic right whale population, and then to the anthropogenic reasons for their current situation.

I’m curious: What were some of the challenges you encountered while reporting and writing the story?

Ed Yong: I think the big challenge for this piece is the same as for any science writing: How do you get a reader to give a shit? And specifically: In a news ecosystem that is increasingly filled with tales of woe and doom for our own species let alone all the others, how do you get a reader to give a shit about a random group of 400-ish animals, especially when those animals are whales, which are popular but also so inextricably linked to doom and conservation—save the whales!—that it’s almost cliché?

I think the solution is twofold. First, establish that these animals are individuals, not numbers. The death of six whales is not just a reduction in a population count, but six individual tragedies, the final chapters of six stories, a source of grief for six families. This is both a handy narrative device and also an act of journalistic and scientific truth, as study after study reminds us of the importance of animals as individuals and not just interchangeable faceless avatars for their species.

Second, make readers care about the people who care about the animals. Tons of people are dedicated to saving these whales; I want to hear how they’re coping, as characters in their own right of course, but also as emotional tethers to a species that many readers may have no connection to.

ND: About one-third of the way in, you take a step back from the ongoing deadly trend and consider the ways in which these whales are dying. Those two paragraphs—the ones starting with “Ship strikes. Entanglements.”—are a gut punch. When, during your reporting, did the horrible reality of these whale deaths land in your consciousness? And what was it like, crafting those paragraphs?

EY: Did I say twofold? Maybe it’s threefold, the third being cutting through euphemisms and going beyond statistics.

One of the things that first drew me to this story was the simple stat that 1 percent of all North Atlantic right whales died in a month. That’s compelling, but a conservation story cannot just be about stats. When the UN released its recent report and every news outlet wrote about how one million animal and plant species are now threatened with extinction, I read dozens of stories about it and found them all cold. The numbers feel unanchored, formless. I know they’re grim but I don’t feel they’re grim.

With the whales, clearly they’re dying, but I wanted to know how. And when you write about conservation, you end up with a lot of terms that encompass important concepts—habitat fragmentation, human-wildlife conflict, and so on—but are so removed from the actual lives and deaths of wildlife that they have almost become euphemisms. When you say a species is dying from habitat fragmentation, what does that actually mean? Like, not technically, but for it? Same thing with “ship strikes” and “entanglements”: These are easy phrases for bad deaths.

So right from the start, I wanted to find out exactly what happens when a whale gets struck by a ship or gets entangled by a line. And fortunately, a paper had been published a week before that spelled it out, and let me tell you, reading it was a journey. It was horrible to read. It’s horrible to write about. As a writer, it does help to focus on the craft, to shift into a weird clinical mindset where I focus on constructing a piece. I know how to make a sentence work, how to structure a paragraph, how to put emotional beats so they’ll land most effectively. And that creates just enough detachment, I think, to shoulder the emotional brunt of writing about whales dying in truly horrific ways.

But man, after finishing, I took a long walk.

ND: Where did you find the idea for this story?

EY: This was a very rare example of a press officer pitch that I read and took up!

ND: And how did you find the people you spoke with?

EY: I can barely remember now, but I suspect that I googled a ton of existing pieces about these whales, and also searched for organizations and people who work on them (of which there are many) with a preference for female voices.

ND: This is a news story, yet it has a feature lede. Why did you decide to go with a more narrative start, rather than a straight news opening?

EY: When I can, I always do. Most of my Atlantic stories have feature-style ledes, which is a reflection of my preferences as a writer, and my interpretation of our magazine’s ethos. Our editor-in-chief has said a few times that people don’t come to the Atlantic to read the news, but to learn what to think about the news. And I try to bring that sensibility into all of our coverage.

Yes, because of its timeliness, this is by definition a news story about some dying whales. But it’s also a piece about thinking about animals as individuals, with families and societies, and about understanding what those individuals go through when a species heads towards extinction. When doing that kind of piece, it just seems natural to me to use a more features-y approach.

People often talk about ledes in terms of grabbing attention, and conveying information. All true, but ledes are also signals: Their tone and style cue readers into expecting a certain kind of story. And personally, as a reader, when I read a standard inverted-pyramid news lede, I know that I mentally prepare myself for fast, skimmy reading. If I read a narrative start, I prepare myself to read the whole piece. News structures evolved in a certain media ecosystem, and they’re great for conveying small amounts of information efficiently. But I also think that they’re utterly unsuited for many kinds of science stories, and I think we shouldn’t be beholden to them, even when what we’re writing about is ostensibly news.

ND: Are you optimistic about right whales’ chances of surviving as a species? Do you think we can help turn around their situation, or are they too far gone?

EY: Oof. I think there’s one good reason to be positive: Unlike for many other endangered species, there aren’t a ton of moving parts that are affecting the fates of these whales. There are really two main threats, and they are both solvable. Ship strikes. Entanglements. We need to stop hitting these whales with boats and wrapping them up with fishing gear. Sure, there are other issues, but solving those would go a long way. Can we solve them? ¯_(ツ)_/¯

I feel like most people in conservation are optimists by nature, and kind of have to be to do that work. I am not. I believe that people can do amazing things, and a lot of very dedicated folks want to help these animals survive. But I think their fate, and the fate of everything else, ultimately depends on massive systemic changes in the way we live, and I would be lying if I said that current events make me hopeful about our ability to enact massive systemic changes for social good.

But I think that whether optimist or pessimist, one of the most important things we can do in a shitty world is to bear witness to suffering. To see it, and name it, and talk about it. Conveniently for journalists, that is literally what we are paid to do. I write these pieces in the hope that they’ll make a tiny dent in moving our collective consciousness towards valuing wildlife. Maybe that’ll help. Maybe it won’t. But if the North Atlantic right whale goes extinct, it damn well won’t do so silently.

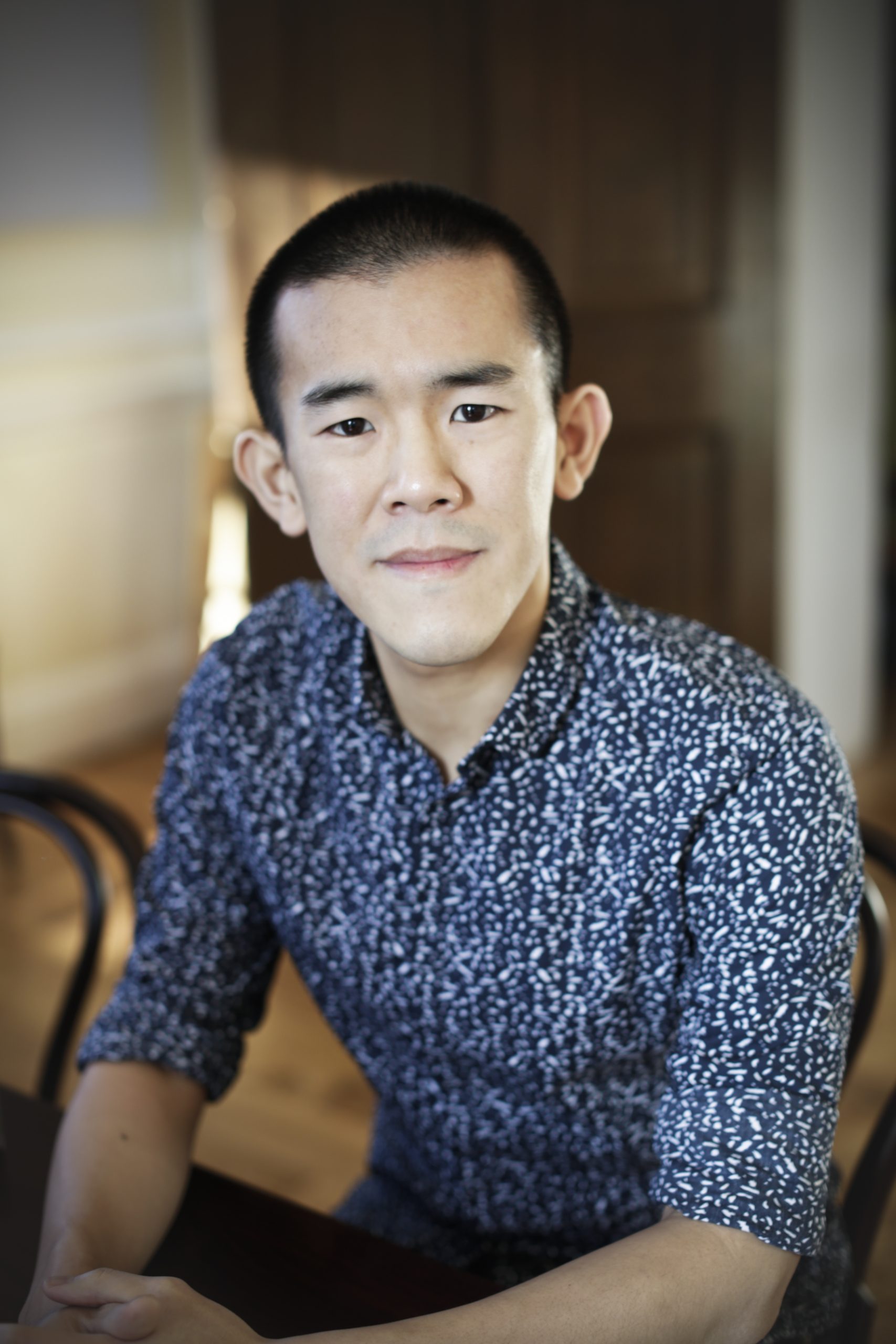

Ed Yong is a science journalist who reports for The Atlantic and is based in Washington, DC. His work has featured in National Geographic, The New Yorker, Wired, and more. He has won a variety of awards, including the National Academies Keck Science Communication Award. I Contain Multitudes, his first book, became a New York Times bestseller and inspired an online film series, an anthology of plays, and a clue on Jeopardy. He has a Chatham Island black robin named after him. Follow him on Twitter @edyong209.

Nadia Drake is a science journalist and contributing writer at National Geographic. She frequently writes about astronomy, planetary science, and various jungle adventures—and tries to report from the field whenever possible. Nadia has a PhD in epigenetics from Cornell University and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz, and her work has also recently appeared in The New York Times, Scientific American, and The Atlantic. Follow her on Twitter @nadiamdrake.