The following story diagram—or Storygram—annotates an award-winning story to shed light on what makes some of the best science writing so outstanding. The Storygram series is a joint project of The Open Notebook and the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing. It is supported in part by a grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. This Storygram is co-published at the CASW Showcase.

Suicide. Guns. Mental health. Not exactly light fare. Yet with thorough reporting, careful structure, and a compelling lead character, a story about such serious social issues doesn’t have to read like a white paper or a variant of the same opinion piece on gun deaths you’ve already read (or skimmed) 20 times. In her measured and thoughtful piece “Surviving Suicide in Wyoming,” FiveThirtyEight’s Anna Maria Barry-Jester uses material gathered to maximum benefit, delivering an informative, sensitive, and nuanced look at a difficult issue.

Story Annotation

“Surviving Suicide in Wyoming”

Self-reliance helps people thrive in a landscape that’s big and tough, but it can also put them at risk if they get into a personal crisis.Savvy title and deck. Halfway through reading the piece, I thought back to the title with newfound appreciation for the tone it establishes, and for what it does not contain, which is the word “guns.”

By Anna Maria Barry-Jester, FiveThirtyEight

https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/suicide-in-wyoming

Photos by Daniella Zalcman. Graphics by Ella Koeze.

(© ESPN. Reprinted courtesy of FiveThirtyEight.com.)

Kenny Michelena is, by just about any measure, a tough guy.This opener is no barnburner, but it’s elegant nonetheless. Good stories are about people, and right away the reader gets to meet one. It’s also quick, conversational, and not showy. Kudos. He was born and raised on a ranch in rural northwestern Wyoming and remembers that after class in elementary school, the bus driver would drop him off wherever he saw the family tractor, so he could go straight to work in the fields. He worked just about every day of his life from the age of 8, first lambing sheep and plowing fields, later helping run the farm. In his 30s, when the ranch became unprofitable in a shifting economy, he drove trucks packed with cattle and other animals across the country, backbreaking labor that put him on the road for weeks on end. High marks for tempo and, again, not showy. What do I mean by tempo? The writing has a breezy feel. The reader can move quickly through it, not because skim-able prose is the goal, but because accessible prose is the goal. Tempo has another meaning for a story like this one, which we’ll get to in a moment.

Then, several years ago, the pain started. It began in his shoulder, but it quickly took over his whole body, preventing him from working. There were days when he could hardly get off the couch. “I was raised where your pride, your reason for being alive was work,” Kenny said.The reporting for this piece yielded a lot of great quotes that are deployed effectively to provide feeling or encapsulate a big idea. Quotes used to serve up information that should have been paraphrased are a great way to lose readers.

He went to several doctors, and none could find anything wrong with him. He remembers one telling him he was just an overweight truck driver looking to collect disability.

It wasn’t until early in 2014, when he consulted a physician assistant in a nearby town, that he started to get some answers. The physician assistant said she’d do the X-ray, but she also wanted to draw blood. Test results showed that he had hemochromotosis, a genetic condition that causes excess buildup of iron in the body, which can lead to liver and heart failure, among many other life-threatening concerns, if left untreated.

Need help? Call the toll-free National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK.

“Maybe in a bigger town, or with more doctors, that wouldn’t have gotten so bad,” Kenny, now 58, said recently from a reclining chair in his living room, looking out through the kitchen to the fields and mountains in the distance.

The diagnosis brought Kenny some solace, but the searing pain remained. It was just one of the many problems swimming around in his head, pulling him deep inside himself that summer. The aching wouldn’t let him sleep or work, so his schoolteacher wife, Lisa, was supporting them. And there was the family ranch that he and his brother had different ideas about how to manage but could both agree probably wouldn’t turn a profit again. He began to worry about money. He thought, as he sometimes had since he was a teenager, about using one of the dozen of guns he keeps at home to end his life.The best journalism instruction I ever heard was this: Just tell what happened. Easier said than done, but when you have the material, as Barry-Jester does here, this mantra can get you far.

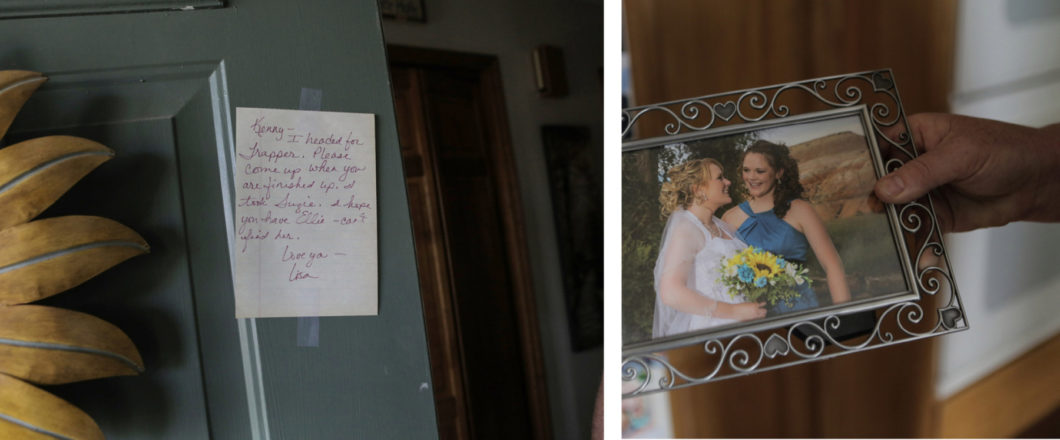

One of his two daughters, the one still living at home, got married and moved away. He knew that would hurt emotionally, but it was worse than he had anticipated. “Nobody wants to see their kids go, but I’d been dreading it since the day they were born,” Kenny said. He made it through her wedding and then brought his other daughter’s beloved animals to the state fair a few weeks later — the sisters had been state champions a few times; he didn’t want to disappoint them. “I held up long enough to get those two things done, and then I just let go,” Kenny said.Small scenes can paint vivid pictures. The reporting likely yielded other examples of Kenny’s emotional descent, but this one is gutting. Again, smart use of material blended with powerful quotes.

He woke up early one morning in August to do a day’s work for the local agriculture cooperative, but he never made it. This is a bit clunky and could have used some smoothing over. That is an opinion, of course, but read the sentence aloud. See what I mean? Kenny told Lisa that he loved her, but he thought they’d be better off without him; he couldn’t take the agony anymore and wanted to end his life. Lisa called a crisis hotline, and then put Kenny in the car and drove him three hours from their rural home to the hospital in Billings, Montana.

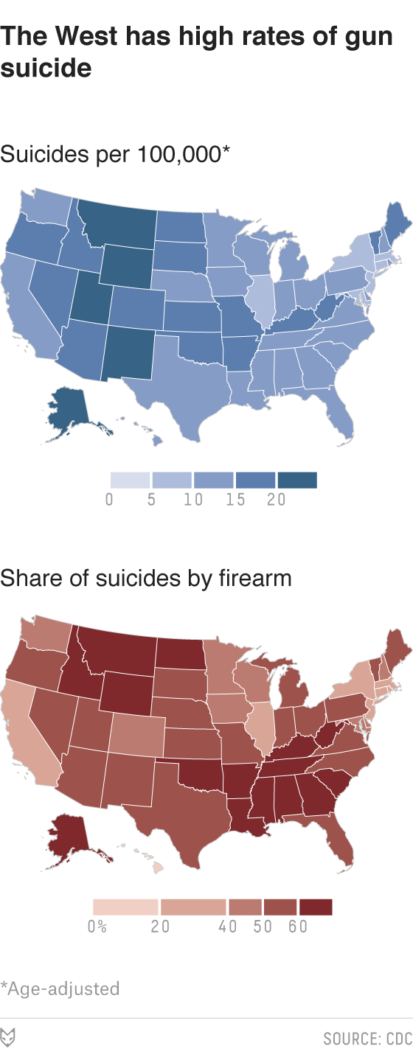

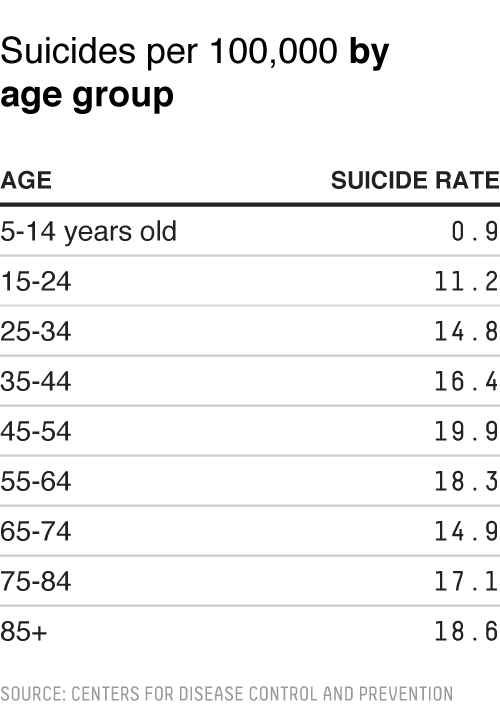

As a middle-age white man living in the mountains of the Western United States, Kenny is among the demographic of Americans most at risk for suicide in the country. With a suicide rate of 44 per 100,000, men in this age and geographical group have more than three times the risk of dying by suicide than the national average. In Wyoming, approximately 80 percent of suicides are men; a quarter are men ages 45-64.And here’s the nut, or most of it. It’s the figures that so many FiveThirtyEight stories are built on; numbers that, upon scrutiny, reveal that we don’t know the world as well as we think we do. That kind of premise can make for gripping writing, provided real people have substantial presence in the piece.

Though firearmsThis really worked for me. The nut above, focused on suicide, sets up an interesting story all by itself. Yet by holding the firearms connection until the next paragraph, the writer is saying: But wait. There’s more. are the third-most common method for attempting suicide, they are responsible for the largest share of suicide deaths because they are so lethal. Nationally, nearly two-thirds of all deaths by firearm are due to suicide, and Wyoming has had the highest rate of suicide by firearm of any state over the last 15 years. Studies have linked higher rates of gun ownership with increased risk of suicide death, but in Wyoming, which also has one of the highest rates of gun ownership in the country, this is an unpopular topic. As Tom Morton of the Casper Star-Tribune put it in a series of articles about Wyoming’s suicide epidemic, guns and suicide are the “third rail of Wyoming culture.”A clever structural move starts here, one that enables still more twists. This paragraph is about guns as a method of suicide. The reader is about to find out, however, that the connection between guns and suicide is nuanced. Instead of just saying that, though, Barry-Jester unspools the ideas in such a way that the impact of each twist is felt, not force-fed. You’ll see what I mean a few paragraphs down, where I’ve added the label “Guns Tease No. 2”

The high suicide rate isn’t news in Wyoming. “It’s certainly not going down this year. There’s a ton of concern, and nobody has any good answers,” said Mark Russler, the executive director of Yellowstone Behavioral Health Center, a community mental health program in Cody. Russler is responsible for much of the community mental health work in northwestern Wyoming. Despite more than a decade of concerted efforts to reduce the suicide rate, it continues to rise in the Mountain West. But that’s true all over the country — in every region, among every age group under 75, and among nearly every racial and ethnic group.This is a smart editorial play. Get the experts to establish what is essentially a mystery to solve, or at least explore, and you up the chances that readers will stick with you. This passage also makes it harder to dismiss the suicide issue in Wyoming and the West as not relevant to the life of a reader in Chicago, Orlando, or rural New Hampshire.

Local culture is a common explanation for the high rate in the West. In Wyoming, people call it the “cowboy-up” mentality — the get-your-shit-together, pull yourself up by your bootstraps, can-do attitude that they say is bred into children from a young age. That self-reliance helps people thrive in a landscape that’s big and tough, said Russler, but can also put them at risk if they get into a personal crisis.

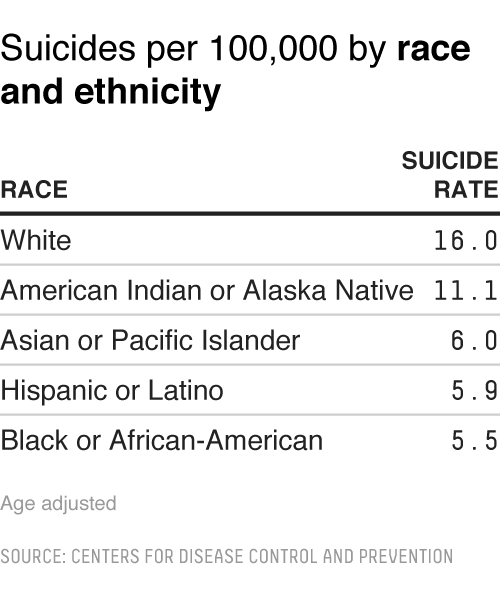

Comparing health statistics in Wyoming to those from states in other parts of the country can be difficult because the population is so tiny (people describe the state as “a small town with a long main street”). But the trend in the Mountain West as a whole is clear, according to Carolyn Pepper, a professor of psychology at the University of Wyoming. She recently took a sabbatical to study why suicide is so common in the Western mountain ranges; using data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Multiple Cause of Death database, she calculated just how bad the problem is and what might be causing it.1 Suicide rates have been higher here than in other regions for nearly a century, and while the rates are highest for middle-age white men, they are elevated for all sexes, races and ethnicities, especially American Indians, compared to their counterparts in other parts of the country.

“I kept hearing, as I talked to people out here, that it’s all about white men in rural areas, middle-age white men. And it’s true that, statistically, that’s the group most likely to commit suicide,” Pepper said. “But when you start looking at the data, this region of the country leads for men, for women, across all racial groups, across all ethnicities. It’s not just a rural problem, whatever it is is also in urban areas, as well as everywhere in between and across all age groups.”

Pepper thinks that means experts need to look beyond just white men and see what regional factors might explain the problem. Rurality is certainly one, as is the isolation that goes with it; Wyoming is nearly twice the size of New York state but with only 586,000 residents has less than 1/30th the population. She also notes that self-reported depression isn’t higher in the mountains, but alcohol and drug abuse are. Unemployment and low income are associated with high risk of suicide; Wyoming’s employment rate withstood much of the recession of the 2000s, but a recent drop in the prices of oil and minerals, which form the foundation of the state’s economy, is starting to wreak havoc on the finances of many families. There’s also the high rate of gun ownership.Here’s Guns Tease No. 2.

After the brief hospital stay and months in therapy, KennyAnd now we’re back to Kenny. Thank God. Big props for pacing and balancing character with issues. Even the most urgent and eloquent writing about statistics, policy, and public health runs the risk of losing many readers whose engagement depends, at least in part, on their interest in the fate of individuals. Just above this paragraph, I had scribbled in the margin: “Back to Kenny soon, I hope.” said many of his life worries are still there, but things are very different today. “I can say right now that I’m better today than I was two weeks ago,” he said. “It’s hard to explain, it’s like I had to restructure my life. It took a lot of people a lot of time, but I’m happy to be alive.”

If you’re enjoying this Storygram, also check out two resources that partly inspired this project: the Nieman Storyboard‘s Annotation Tuesday! series and Holly Stocking’s The New York Times Reader: Science & Technology.

He said a lot of support has come from his family, even if they didn’t understand what was going on at times. He joined a church last year, and has spent time with the pastor, with whom he hit it off immediately and now counts as a friend. He was prescribed a few different regimens of medicine to help with his anxiety and depression, and feels lucky he found the right combination and dosage, since previous medications hadn’t helped. Before that happened, he’d wake up in the middle of the night, filled with what he calls the doom and dread, a sick feeling in his stomach that wouldn’t let him sleep. “The first night I was in the hospital, that happened that night. And the next day, I saw a doctor up there and she put me on some different medication, and that waking up, that never happened again,” Kenny said.On the one hand, this is a fairly typical example of how stories like this one often progress: The central character turns a corner and gets better, or at least starts to get better. On the other hand, now is a good time to pause and appreciate the work the writer has done to build trust with the source, to get him to open up about such personal information. Think about how much thinner this story would be if the writer had spoken with Kenny for 30 minutes by phone and that was it. Or worse, just emailed some questions.

Ashley Fauber has been Kenny’s therapist since right after the eventWhich event?; after Kenny was first released from the hospital, he made the three-hour round trip drive from his rural home to Cody several times a week to see her as part of an intensive therapy program. Fauber said she often asks patients, “What made you come through my door? Because my door isn’t easy to come through.” Like Kenny, a lot of her patients are used to figuring out their own problems, never asking for help. Kenny said later if it hadn’t been for his wife and daughters, both their support and his desire to be there for them, he never would have made it that far.

Efforts to prevent suicide mostly fall in three broad categories: means reduction, which lowers the likelihood that someone in crisis will have access to a way to harm herself; awareness, so that people know where to get help and the general public knows how to spot someone in crisis; and perhaps most important, changing health care, by training primary care physicians to recognize symptoms of depression and mental illness as well as improving mental health treatment so that people don’t reach a point of crisis.

Some of the efforts around awareness, such as billboards and hotlines, have shown little success in Wyoming.The unexpecteds keep coming. What I appreciate about this information and Barry-Jester’s approach to delivering it is that it helps push back against the forces of oversimplification, yet without sounding heavy-handed about how wrong conventional wisdom can be. There is no over-the-top, voice-y writing like: Face it, already. What we think we know about suicide and suicide prevention is utterly and completely WRONG. There are many occasions when that style of writing is appropriate, if not masterful (RIP Tom Wolfe). Barry-Jester decided that this isn’t one of those occasions and I agree with her. A 2009 study found that such efforts may increase awareness but they appeared to have no effect on reducing suicide or getting more people to seek treatment. AnotherLinks here, and throughout the story, play the subtle but important role of reminding the reader that the reporter has done her homework. found that teenagers felt less likely to seek help if they had seen a billboard. Russler said his organization handled the calls from a hotline set up a few years ago, and just 12 phone calls were received over the six months that it ran in Park County (he also notes that none of those people actually came in for services). “We’ve thrown a ton of money at suicide prevention; all the attempts to increase awareness, media campaigns. That’s come and gone, and it hasn’t made a dent,” he said.

Reducing access to lethal means is one of the few tactics that has been shown to prevent suicide at a population level, either by making it more difficult to get a hold of a highly lethal method or by making that method less lethal. For example, particularly lethal pesticides were restricted in Southeast Asia, and the quantity of carbon monoxide in residential gas was reduced in the United Kingdom. But reducing the risk in that way isn’t always straightforward. In a state such as Wyoming, where firearms were involved in the largest share of deaths but are widely owned and used, it is a particularly complicated topic.“Particularly” twice isn’t particularly egregious, but this final sentence feels … unfinished. By this point the reader knows the overlapping issues of guns and suicide are “complicated.” The writer needs to do more than state that.

There is a well-established relationship between individual firearm ownership and suicide by firearm.Now for the payoff. The writer has taken us through the issues and challenged some common assumptions. A reasonable reader arriving at this point in the story has not only learned about Kenny’s struggles, but also followed along with the writer on her search for increased understanding of the connection between suicide and guns. If she had started here, with these studies and numbers, this article would be more of a polemic, and, I would venture, less likely to engage anyone who wasn’t already a staunch supporter of gun control.More guns per household at the state level was also a strong predictor of suicide rates for both men and women, according to a May study from Boston University that looked at data from 1981 to 2013. Gun rights advocates have made the case that people will find an alternative method if a firearm isn’t available. And a 2008 survey commissioned by the state of Wyoming found that three-quarters of residents didn’t believe that reducing access to firearms can impact the state’s high suicide rate.

While the research on the subject is mixed and very limited, it appears likely that suicide attempts are impulsive acts that can be prevented sometimes if the means of a planned attempt are taken away. And because other means are less lethal, not having access to a firearm can still be lifesaving, even if an attempt does take place. About 70 percent of survivors won’t go on to attempt suicide again, and 90 percent won’t die by suicide, according to a Harvard review of studies on survivors. That applies not only to firearms but to other methods, as well.

“We know [that] when people are in crisis, they use the method that is available to them,” said Terresa Humphries-Wadsworth, director of suicide prevention programs for the Prevention Management Organization of Wyoming, which manages all community suicide prevention efforts for the state. “If you remove one of those methods, whether that’s the pills or whatever, then they are less likely to go out and seek an alternative method, because they aren’t very good at problem-solving in that crisis moment.”

Those trying to address suicide in Wyoming say that national conversations about gun control often hurt local efforts to reduce access to firearms for people in crisis. BJ Ayers, a mother of three and the founder of Grace for 2 Brothers, a nonprofit organization in Cheyenne that works on suicide prevention, has made suicide prevention her life’s work. “I don’t want to take your guns away; I want to make sure that the gun is not accessible to a person when they are in a mental health crisis,” Ayers said. It’s been hard for her to get people to see the difference.

Gun violence is a deeply personal topic for her. In 2005, her youngest son took his life. Four years later, her middle son did the same. Both young men used firearms. Ayers and her organization have spent the last 10 years trying to beat back the suicide rate by building support networks for survivors, educating the community on suicide and holding an annual walk to raise awareness in hopes that the numbers will drop. “When we talk about gun violence, I just ask that we put our political views aside, and realize that this is a conversation about access to lethal means for someone who is in a mental health crisis; it has nothing to do with control,” Ayers said.

At his first appointment, Fauber asked Kenny whether he had any guns at home. He has a beautiful wood and glass gun case, which he made, in the corner of the family’s sun porch, and another rifle case sits in the living room. He keeps one in just about every vehicle, another in the workshop. “I don’t go anywhere without my gun. I rarely use it, but I guess it’s habit,” Kenny said later.

Out the front windows of Kenny’s cabin-style home, across a winding gravel road and a handful of other ranches, lie the Big Horn Mountains. Hunting there for elk was the only vacation he remembers taking as a child. Recently, hobbling around on a broken foot that was crushed by a young horse, he said he’d spend all his time riding around out there if he could. Having a gun is practically a necessity for survival in that landscape, which is home to bears, mountain lions and coyotes.

Kenny told Fauber that he did have guns and reluctantly told her that he was still thinking about using them to harm himself. By his next appointment, he admitted to her that they weren’t out of the house. So she called the local sheriff and, along with several other officers, he went over and moved them to Kenny’s brother’s house. Fauber remembers how concerned Kenny was about whether he’d get them back. He still has trouble talking about it, even as he’s opened up about other aspects of his struggle with depression.

“Was it hard for me to admit that I wasn’t safe around my guns? Yeah, it was really hard,” Kenny said. After he was out of crisis, the guns were brought back. Today he has proudly holstered them in their display cases.Again, Kenny proves to be a superb source, and the writer proves her skill at coaxing him to share.

Even when someone has already shown himself to be suicidal, we aren’t always good at keeping him safe from lethal means. A recent study from the University of Colorado looked at suicidal individuals in seven states who had made it to an emergency room, and found that more than 50 percent hadn’t been asked whether they had a firearm at home, or any other lethal means of attempting suicide.2 “We are missing the chance to save a lot of lives,” the study’s author told Science Daily.

Russler said that more often than not, families are supportive of keeping firearms away from suicidal members. “A lot of times someone will tell us they don’t [have a gun], but then their family members will tell us, ‘Oh yeah, they’ve got a handgun in their truck, it’s loaded.’” He acknowledged that making it harder for someone to get their hands on a means of attempting suicide is incredibly important, especially in a place where people don’t readily seek help, but he doesn’t think gun control laws are the answer. “I would not be a proponent of reducing access to someone owning a firearm,” Russler said, although he is in favor of using the screening that’s already on the books to make sure suicidal people aren’t buying firearms,3 and more generally to keeping guns stored in a way that makes them harder to get when someone is in crisis.This is quite a passage. As far as writing strategy, the content delivers a clear message: Solutions to this problem are not easy. Barry-Jester also lets her source speak; too often writers will get in the way, interrupting the speaker with commentary or attempts at distillation that may not be necessary. In addition, this paragraph tees up yet another twist. The next few sentences are still about firearms and access to them, but everything that follows looks beyond guns, to mental health, availability of services, changing attitudes about depression, and so on. With a light touch, Barry-Jester is showing, without saying, that all is not what it seems.

Wyoming is handing out gun locks in some areas in an attempt to reduce immediate access to firearms. While it’s hard to reduce the lethality of a firearm, the gun locks add a step to overcome before someone is able to use one, much like storing it in a locked case and keeping the ammunition separate. But Pepper said it’s unclear how many barriers need to be in place to really reduce the risk; moving guns out of a room probably isn’t enough, but moving them out of the house might be. It’s unclear where gun locks fit on that spectrum.

The prevention programs in place in Wyoming,This transition from the previous paragraph is a little jarring, jumping from the quite specific matter of gun locks and small barriers to Wyoming’s (suicide) prevention programs generally. A little more connective tissue between the more specific point and the zoom-out could help. which mostly come from a database of evidence-based practices kept by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, have all been successful in small communities in research settings. They haven’t been deployed at scale, however, in a way that has reduced the rate of suicide. As the national suicide rate rises, officials in Wyoming hope they can change that.

In 2012, Wyoming began a statewide push to get people trained in QPR, which stands for Question Persuade Refer. The idea is that, as with CPR training (the similarity in the names is not a coincidence), if enough people in a community are trained to recognize the signs of crisis or suicidal behavior, then someone will be able to intervene and get a person to treatment before they harm themselves. Wyoming has gone all in on the program: It has the highest concentration of trainers for the program of any state, and Humphries-Wadsworth said more than 10 percent of adults in the state have been trained. However, the impact of the program isn’t clear yet, she said, and it will be several years before it is.

Like most things in Wyoming, mental health treatment is often far away for people in rural areas. Still, the state has a fairly extensive network of community mental health programs, most of which accept payment on a sliding scale. The most common problems that people seek treatment for are affective disorders, such as depression and anxiety and bipolar disorders, which account for nearly 30 percent of the problems patients in the program experience. Alcohol-related problems are next, making up nearly 18 percent. All of these disorders are associated with high rates of suicide.

In the northwestern corner of the state, Russler and his colleagues are testing the program that Kenny took part in, called Brief Intensive Treatment.This is deft stitching of macro-level issues with the life of the main character. The idea is to help prevent suicidal people from having long stays in a hospital, and to get them more targeted, intensive therapy that involves the whole family. The first published evaluation of the program found it to be more effective at treating patients than traditional intensive therapy programs, though further studies are needed to determine if, and how well, it’s working.

Russler said he feels good about the programs in place, but thinks the reason they haven’t reduced the state’s suicide rate is that the highest-risk people are often the hardest to reach. “When we can get people to us, to treatment, they usually do well,” he said. While some people question whether there are enough mental health providers in Wyoming, Russler suspects that’s not the problem. Sure, they could use more specialists, he said, but the real problem is getting people into the mental health system. “The people committing suicide, they’re the ones we’re not seeing.” That’s why he thinks changing local attitudes about seeking mental health care, which he said is often seen as a sign of weakness, is key.

Russler said he’d mainly like to see mental health professionals placed into primary care settings, such as family doctor’s offices, and primary care doctors that are trained in recognizing signs of depression and anxiety.

When KennyOnce again, Barry-Jester’s sense of tempo and dosing shines through. If discussion of mental health delivery were to continue much longer without a return to Kenny’s story, the writer would have risked losing readers. was looking for the source of his shoulder pain, he went to several doctors, and he exhibited other kinds of distress that could have been recognized by a trained professional as clues that his mental health was not good: sleeplessness and anxiety, among many others. There’s evidence that this missing of signs is common with people who attempt suicide. A 2014 study examined the records of 5,894 people in seven states who died by suicide between 2000 and 2010. The researchers found that 83 percent of those people had received some sort of health care in the year leading up to their death (64 percent of those were primary care visits), yet only half had had a mental health diagnosis. While suicide attempts may often be rash, desperate decisions, the depression and anxiety that often lead up to them are not, particularly in adults.

“I wish you could have seen him then, so you’d know how far he’s come,” Fauber said recently, recounting Kenny’s progress. “He’s so much fun,” she laughed, musing that she could easily sit around and talk to him all day, every day. When he first saw her, he was reticent, and had a hard time opening up about himself, what he was feeling. He was deeply concerned about not being able to work and provide for the family, and overwhelmed by the dark feelings and physical pain he was experiencing. Fauber started working with him the way she does with most patients — by explaining how the brain works. “Everybody wants to know why they feel the way they feel. I will literally draw a brain on the board,” Fauber said.

Kenny slowly opened up about some of his traumas. He can talk about them now, though he isn’t totally sold on the idea that triggers from his childhood are affecting him today. He says he had a great childhood: His mom kept a big garden and had something freshly baked for him nearly every day when he got in from working. His father kept up to 1,200 sheep, sometimes lambing a hundred in a day during birthing season.

But he also acknowledges that there’s another side to his story. An alcoholic father who suffered from chronic pain that likely came from the same blood disorder that plagues Kenny. Hard work from an early age that sometimes leaves him longing for a childhood he never had. Multiple family members have been treated for depression. Kenny now sees the connection between those things and his own battles. “I still feel bad, maybe even ashamed, that I fight depression,” he said, but he also says he’s learning to accept that the chemical and emotional legacy isn’t something he can change.

Kenny’s youngest daughter recently came home with a tattoo. It is of a small semicolon on her ankle, a symbol that represents a movement to acknowledge mental health concerns and promote suicide prevention. She told him she was glad he put a semicolon in his life instead of a period.This short graf confused me. There isn’t enough on Kenny and his younger daughter’s relationship in the rest of the piece to make this pay off as an ending/near-ending.

Kenny hasn’t talked to many people about his struggles with depression. He hasn’t told his neighbors, and he chose to see a therapist in a town an hour and a half away because when he went to a center nearby, he was connected in one way or another to most of the people in the office. He was clear, however, that if he could help prevent someone else from getting into his situation, sharing his story would be worth it.Strong ending. Neither cheery nor dismaying, it sounds sincere. What more could a writer want?

This article is part of our project exploring the more than 33,000 annual gun deaths in America and what it would take to bring that number down. Our podcast What’s The Point is highlighting the project all week.

A Conversation with Anna Maria Barry-Jester

David Wolman: Tell me about the genesis of this project. Was it going to be a feature from the get-go?

Anna Maria Barry-Jester: This story was one part of a group project exploring gun deaths in the United States. My colleagues at FiveThirtyEight and I were really struck by the amount of news coverage that mass shootings garner, as well as their role in shaping gun policy, and how far removed some of the proposed policies are from the most common ways that people die by firearms. We decided to look at these deaths in the ways that public health experts do, breaking them out into groups that would allow us to ask: What would it take to save their lives from gun violence? I mostly report on public health, so I ended up writing about the group that makes up the largest number of gun deaths: white males who die by suicide.

DW: How do you approach interviewing someone like Kenny Michelena?

AMBJ: I met Kenny through one of his therapists. I’d been talking to people all over the Western mountain ranges of the United States, an area with an incredibly high rate of suicide, for several weeks already. I spoke at length with many practitioners—doctors, emergency room workers, researchers, and therapists—about what worked to prevent suicide, as well as what didn’t. In each interview, I would ask about patients who might be willing to share their stories with me.

One thing that I felt was very important when I first met Kenny was that I explain right up front that this story was part of a series on gun deaths—Kenny has been a hunter and rancher since he was old enough to walk, and he told me that firearms have been part of his daily life for as long as he can remember. The story isn’t just about guns, but I wanted him to know that I would be discussing gun deaths in relation to his story—both to understand how he felt about them as a public health concern, but also because he deserved to understand that context before he agreed to share such personal information with me. Among other things, multiple mental health professionals had talked to me about how the national fight over gun legislation has made their work more complicated—a suggestion to temporarily remove guns from the possession of someone in crisis often leads to concerns about infringement on the right to bear arms.

As for the interviews, I knew there was sensitive information I would have to ask and know in order to write about Kenny and his family. But all the research on suicide also suggests that the attempt on his life was hardly the whole story. So I started by asking him to explain his life on the ranch in rural Wyoming—how he spent his days, what his childhood was like. I’ve heard from his therapist and others that he was a very reserved man not too long ago, but he was incredibly generous with me. He taught me about lambing sheep and how the economics of ranching have changed over time. He also told me about how his Basque ancestors arrived in the state, and walked me through what he knew about his family. These things weren’t just details—they all turned out to be important context for Kenny’s physical and mental health history.

DW: What about other sources for the story? How did you go about deciding the different voices you wanted to bring to the piece, and then how did you seek them out, beyond basic criteria like lives-in-Wyoming?

AMBJ: I did a lot of interviews for this story, with people in a variety of geographical locations. Pretty early on, I suspected that the story might be set in Wyoming because it was in some ways the most extreme of the Mountain West states. But it’s also not really an outlier: we could have told this story in Colorado, Idaho, or Montana, among other places, so I cast a wide net while looking for programs with promising results. I knew I wanted to include a range of voices—the people studying the statistics, people designing the programs and interventions, the lawmakers responsible for making those interventions available through policy, and of course, most importantly, the people who were supposed to benefit from those policies. The goal with this story was to write about what we know might successfully prevent suicides. So the first thing I did was look for programs that had some kind of evidence of success behind them.

DW: In naming subjects in stories, it’s usually first and last name, once, followed by last name only. Did you and your editors talk about that at all? Why did you opt to go with Kenny throughout?

AMBJ: This was one of the main things in the story that changed from first to final draft. Last name on second reference is certainly the convention and is also our house style at FiveThirtyEight. We changed from Michelena to Kenny fairly far along in the process, after the main edit was complete and the story had been handed over to the copy editor. The two editors who worked on this story, Simone Landon and John Forsyth, and I talked about it quite a bit and decided that it felt appropriate to express the personal and intimate nature of this story by going with the name that those close to Kenny use.

DW: How did the final version differ from your earlier conception or outline for this story?

AMBJ: I would say this is definitely not the norm for me, but the final version of this story ended up looking a lot like the outline I made when I finished the reporting. The outline, however, was pretty different than what I’d conceived going into the reporting. The main reason was that I didn’t assume that we’d meet someone willing to share their time and personal details, so I had anticipated needing to write a story that rested much more on advocates and health professionals. I was glad to be wrong about that.

DW: On that note, do you ordinarily outline? If so, tell us what that looks like, even if it’s just napkin scribbles. If you don’t, tell us about that, too.

AMBJ: Such a good question! I do outline, usually even for quick, day-of stories. I do it for a few reasons. The obvious one is to get me organized. I am not an organized writer; I tend to get overwhelmed by all of the information and reporting I have for a story. I have a much better time getting through the early-labor stages of the writing if I have a guide. I still stray, or see connections I hadn’t made while outlining that might change things, but I use outlines to break things up, to allow myself to work one section at a time on a longer story.

Another reason I outline, and this extends from something I learned at a two-hour workshop I took with Jacqui Banaszynski at an Association of Health Care Journalists conference a few years ago (I wish every nonfiction writer had the chance to be in a learning space with her), is that the outlining period is a really good time for me to go through all the reporting material and think about the scenes and people I found in the reporting, to figure out how they will anchor each section to help it come alive. This is the point when I sift through all the interviews I’ve done and think about the meaningful moments and/or details that will move the story along and hopefully help readers connect to it.

DW: Do you think about tempo when writing? It seems to me that there is careful pacing here between Kenny-related stuff and bigger-picture material. Was that strategic?

AMBJ: It was definitely strategic to work back and forth between the humans at the heart of this story and the research and statistics behind the issues of firearm-related suicides. At FiveThirtyEight, we orient our reporting around data and analysis—the big picture. But we also try to remember that every data point is a person. In these stories where we have the chance to blend our brand of data analysis with traditional reporting, I do try and make sure that we’re moving between the two in ways that allow readers to connect with the people and the issues, but also orient their understanding in the broader picture of what we do and don’t know. Sometimes that means making clear where a person departs from the norm, or letting the people, with all their messy lives and experiences, explain the flaws in the data.

DW: What is a passage, idea, or even just a thought that you’re particularly pleased with, and why?

AMBJ: There’s a section of the story, the part that gets at how the politics of firearms interferes with the work of “means reduction”—essentially, reducing the likelihood that someone in a time of crisis will have access to a way to harm herself. In many ways, it’s the heart of the story. It was also the part that was most difficult for almost everyone I interviewed to talk about, including Kenny. I was pleased with the way we were able to bring that issue together in the passage where we describe how Kenny’s family, local law enforcement, and his therapist worked together to reduce his immediate access to firearms during his most difficult periods.

DW: What has the response from readers been like?

AMBJ: We had a really strong response to the interactive we created examining the 33,000 annual gun deaths in the U.S. People spent a lot of time exploring it, and it had hundreds of thousands of visitors. We also heard from a lot of readers in the Mountain West who have an intimate relationship with suicide, as well as many people who were intrigued by the possibility of law enforcement and mental health professionals working together on harm reduction.

DW: I’d like to know an estimate for how much time you spent talking with Kenny. First as a total and then broken into in-person versus by-phone.

AMBJ: I spent several hours talking with Kenny, in person and over the phone. When we first met, it was at his home in Wyoming, after I’d already met with some of the therapists he’d worked with, and after talking to him briefly over the phone. We spent two or three hours in his living room, talking about his life, the ranch surrounding us, and a lot of what he and his family had been through. After that, we lost touch for a couple of weeks. He likes to keep busy, and much of his work was as a truck driver at the time; he was hard to get ahold of when he was on the road. But we eventually reconnected and had a handful of additional conversations, totaling at least a couple more hours of interview time. I also spent a couple of hours on the phone with his wife, Lisa.

Anna Maria Barry-Jester is a multimedia journalist and staff writer with FiveThirtyEight who specializes in public health. She has reported on a wide range of topics, including a mysterious epidemic of kidney diseases killing thousands of agriculture workers in Central America, the rollout of the Affordable Care Act in Latino communities, and the ethics of releasing genetically modified mosquitoes in the Florida Keys. Her work previously appeared in numerous outlets, including ABC News, the Center for Public Integrity, and Univision. The International Reporting Project and the Center for Health Journalism at the University of Southern California have supported her reporting, and she has received awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, the Sidney Hillman Foundation, and the Society for Environmental Journalists, among others. This article was part of the FiveThirtyEight series Gun Deaths in America, which won a 2017 communication award from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Follow Barry-Jester on Twitter @annabarryjester.

A longtime contributor at Wired, David Wolman has also written for publications including The New York Times, The New Yorker, Outside, Nature, and Bloomberg Businessweek. His work has twice been anthologized in the Best American Science and Nature Writing series, and his Atavist Magazine feature about Egypt’s revolution was nominated for a National Magazine Award. A former Fulbright journalism fellow in Japan, he is the recipient of an Oregon Arts Commission fellowship, and he has published four nonfiction books: The End of Money, Righting the Mother Tongue, A Left-Hand Turn Around the World, and Firsthand. He is currently working on a book about cowboys (HarperCollins, spring 2019). Follow Wolman on Twitter @davidwolman.