These days, Science staff editor Martin Enserink is busy editing stories about COVID-19, but two years ago he was immersed in writing a feature about a Spanish doctor’s efforts in Papua New Guinea to eradicate an infectious disease called yaws. This is a scourge many people haven’t even heard of, but for those affected, it can be devastating. Enserink didn’t know how long or emotional the journey would become.

He applied for a travel grant to fly more than 9,000 miles from his home in Amsterdam to the island of Lihir, in Papua New Guinea, just north of Australia. Once there, Enserink saw an effort to give antibiotics to villagers flop. He already knew about scientific disagreement about the feasibility of eradication. But his journey put him face-to-face with the suffering of people with yaws, a bacterial infection that spreads by skin contact and causes skin lesions and painful, sometimes permanent bone and joint damage. But he also saw inspiring research successes and the hope they gave people. In his story, “A Second Chance,” published in Science magazine in July, 2018, Enserink examines Oriol Mitjà’s work with the Barcelona Institute for Global Health and the precarious history of yaws eradication itself.

The World Health Organization nearly eradicated yaws via antibiotic injections decades ago, but efforts declined in the 1970s when the disease was considered 95 percent eradicated and therefore no longer a priority. Ever since, there has been little study of yaws. But when Mitjà proved in 2012 that the disease can be treated with an oral antibiotic, which is significantly easier to deliver and administer, he re-awakened the global push to get rid of it.

Eradicating an infectious disease means wiping it out completely by ending all transmission chains. Over the course of human history, smallpox is the only human disease to have been eradicated, a feat achieved in 1980. And thanks to the efforts of a few philanthropic foundations and the World Health Organization, many global health authorities hope polio and guinea worm will soon follow. Mitjà wants yaws to be on this list.

Here, Enserink tells Seattle-based health journalist Sally James about his ambition for recounting the history of yaws eradication, the controversy over whether it’s feasible, and the experience of those with yaws. In addition to discussing how he gained grant-funding for the reporting and made time for travel, Enserink shares some of the ways the emotional experience of reporting on the ground influenced how he approached writing the story. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

How did you decide to open the story with a diagnostic scene of Mitjà interacting with a sick five-year-old boy and his mother?

When it happened, I felt right away that it was an interesting scene, because it showed Mitjà as a scientist and also as a really kind doctor who had a great rapport, especially with kids.

Did you know, in the moment, that it would be the lede?

I thought it was a strong scene, but at that point I still had a couple of days to go, so I didn’t make any decisions. Then and there, I just wrote it all down and thought, “Hmm, that could be a good lede. Maybe.”

Your opening paragraphs paint this scene in the village, where Mitjà examines the boy, but you don’t mention yaws until the fifth paragraph. Why did you opt for a long anecdotal lede?

At Science we like to cut to the chase pretty fast. You know, sometimes my writers have these long ledes and sometimes, I admit, I shorten them because I feel it takes too long to get into the story and to tell us what we’re going to read. But for these bigger stories, long features, we have started emphasizing a more narrative style.

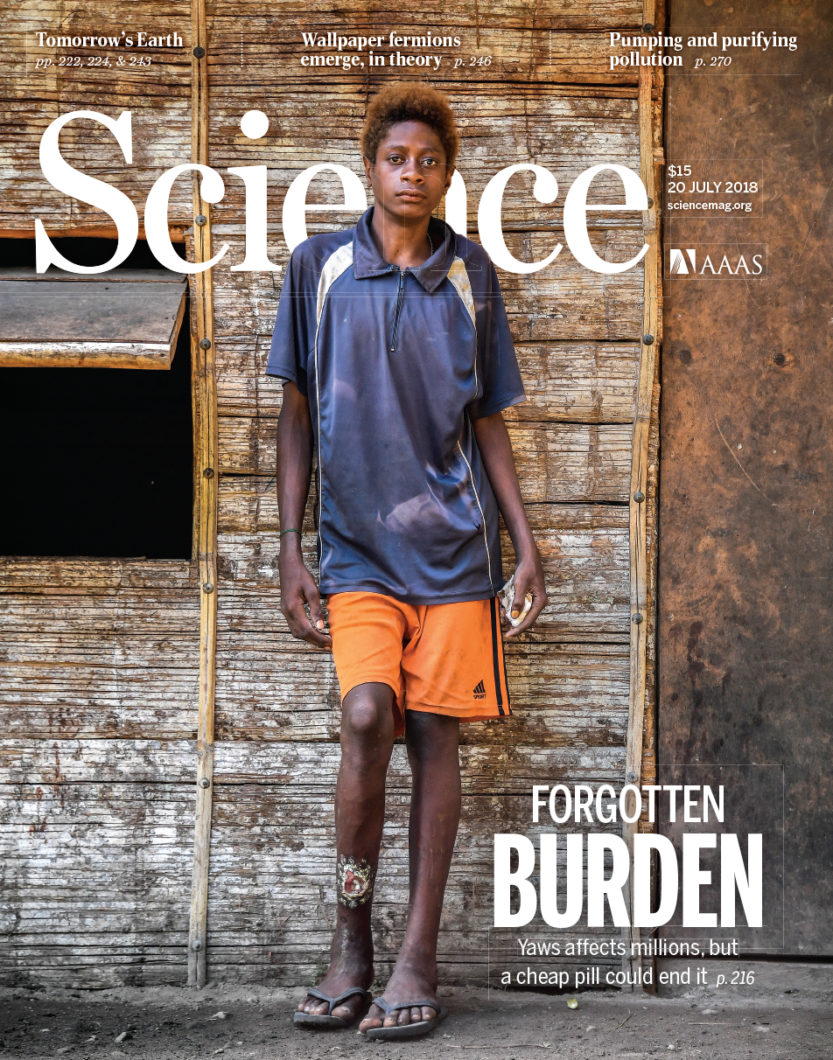

You shared that it was emotionally hard for you to meet Stanis Malom, the 15-year-old with a large, permanent, painful skin lesion on his shin due to yaws. How did it affect you?

Well, it is rare because most people are treated in time, but he hadn’t been treated in time. His leg looked quite gruesome. We visited him and talked with him, and that struck me the most: If he lived in a Western country, you could go to the orthopedic surgeon and break the [injured] bone and put it back together like a puzzle. But there are no orthopedic surgeons there.

As Mitjà put it, the bottom line is, he’s not going to have a happy life. If this guy had had an antibiotic that costs less than a dollar per dose, this could have been prevented.

Sometimes it takes just one person to drive home the disparities, the inequities. It hit me hard. I called my partner that night on Skype and I suddenly broke down. I started crying, and I couldn’t stop.

Did your emotional response change how you wrote the story?

I don’t know. I think it informed my reporting. But I don’t know in what way exactly. It helped me understand what happens if you don’t treat yaws.

How did you strategize mixing on-the-ground scenes in Papua New Guinea with history and reporting on more abstract matters like scientific arguments?

I had several scenes, and I definitely wanted to use them. But I needed to explain a lot of science and history. Because I had discovered Sascha Knauf of the German Primate Center and all of his criticism about yaws eradication, I felt we had to put that in as well. [Knauf has argued that the concept of yaws eradication may be misguided, because even if the disease no longer exists in humans, primates that are infected with the yaws bacterium could pass it back to people.] So basically, I intersperse the scenes from Papua New Guinea with background information, hoping it will pull readers through.

You write that Knauf and another scientist disagree so passionately that one prefers not to discuss his nemesis. Yet, you push him to talk, and you help your readers understand the personal animosity. Why take the time for that?

Personal conflicts are often part of scientific arguments. I like writing about conflicts; I enjoy it. I think [these two scientists] have clashed a few times, and it had gotten very political. Knauf felt he was exposing an inconvenient truth that interfered with the whole eradication drive. Whereas the other camp felt that [Knauf] was just drawing a lot of attention to something that might not be relevant at all. I personally felt it was relevant.

One of my favorite sections is your description of a village event where scientists hope to treat hundreds of people but only a handful show up. This is very disappointing for the researchers. What is the importance of this scene?

I don’t want to be a cheerleader; I’m not a cheerleader for this project. I did my best to examine it and to look at what’s going well and what isn’t. When they took me to this mass drug administration site to see it in person and it didn’t go well, I had to include it. There was never even a thought about not including it.

Tell us why you soften the scene with positive information.

I witnessed that poorly attended village scene, and it was clear things didn’t go well. Mitjà never tried to stop me from writing about it. This is what happens. This is real life. Then the next evening, I heard his associate call it a disaster, and I thought, “Okay, well thank you. I’ll include that as well.”

But when I talked to them later, they made a convincing case that this one site was an outlier. As I wrote, for all of the sites together, they had like 80 percent coverage, meaning 80 percent of the population had been treated. That was not a bad number. It felt right to include that as well.

How did you fit reporting and writing this story into your schedule as a full-time editor?

Most of my job is editing stories. I started out as a writer at Science; I still like to write every now and then. So when this story came up, I felt it was worth taking a bit of time out of my editing.

To cover your reporting expenses, you applied for a travel grant from the Pulitzer Center. What did that entail?

The paperwork was minimal. I had to write a 250-word statement of what I wanted to do and pull together a budget. Basically, I looked up the fares to the island where Mitjà is based, and then I added accommodations and some miscellaneous things. I also added a little bit of money for additional trips in Europe; I wasn’t exactly sure where yet, but I thought I might want to go to Barcelona or maybe to London. It all ended up costing just north of $4,000, and that’s what they gave me.

Your story won the 2019 Communication Award from the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. What do you think made this story a success?

I don’t think I’ve ever written a story where the photos and the text worked so well together. You really see the people that I write about. You see Jeremiah, the little kid; you see Stanis, the 15-year-old boy with a wound on his leg. His photo became the cover of the magazine. I realized how powerful it is to use the scenes, but then even more when you have the photos right there.

Your ending for the story is bittersweet. You take us to a ceremony where Mitjà wins a “Catalan of the Year” award in Barcelona for his eradication work. You write that at home, in Spain, he’s a celebrity for fighting the disease, but that “in the wider world, the disease remained almost as unknown as it was eight years ago.” Why choose this contrast as your ending?

I felt really lucky to be able to attend that ceremony, because it was an important moment in Mitjà’s life. And that was a contrast in itself, you know, from Papua New Guinea to a glitzy theater in Barcelona.

In the next paragraph comes that contrast with the rest of the world, where yaws is still very, very unknown. I felt that was a nice dramatic counterpoint. My first draft actually had a couple of paragraphs after that, explaining how maybe Mitjà could break out and become sort of a global champion instead of just a champion in his own region, Catalonia. But Tim Appenzeller, my editor, said, “Why don’t we just end it right there?” And I think it was the right decision. It ended up more powerful that way.

Sally James is a freelance science writer whose work has appeared in PLOS, Health News Review, Seattle Business, Nieman Storyboard, and many other publications. She is also a member of the National Association of Science Writers. Follow her on Twitter @jamesian.