In mid-March, Adriana Hernández, a photojournalist at the Mexican newspaper El Universal, was sent to document the COVID-19 pandemic in the field. That same day, an editor gave her the bad news: The newspaper was cutting her salary by 30 percent. Hernández had to decide whether to keep working—for even less money and with no support from her newspaper to get the necessary gloves, glasses, mask, and protective clothes—or refuse and most likely be fired.

In the coronavirus pandemic, journalists all over the world have suffered pay cuts or lost jobs. Those still working have had to figure out how to stay safe. For many, that means working from home or, if they have to go out, taking advantage of safety protocols and equipment provided by their publications. But other reporters have been dispatched to press conferences, hospitals, cemeteries, and wherever else the stories are—with no safety equipment or medical insurance.

Latin American journalists may have fared among the worst, with the largest number of deaths by COVID-19. An International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) report published in August found that 171 journalists in Latin America died from COVID-19—the most of any region, followed, more recently, by India. The Latin American countries with the highest numbers are Peru, Ecuador, Mexico, and Brazil.

The pandemic is all the more hazardous for Latin American journalists because of a lack of respect for press freedoms in many Latin American countries, which have long faced significant free-press issues, including censorship, violence, and lack of access to information. Mexico is the deadliest country in the world in which to be a journalist. Latin America is not a monolith, and not every part of the region is equally dangerous. But the broad situation in Latin America is getting worse. Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index says that 2020 has been “characterized by an overall decline in respect for press freedom in Latin America,” with the exceptions of Costa Rica and Uruguay, which have both seen improvements.

In a pandemic, lack of press freedom and labor protection is particularly dangerous because many journalists feel they can’t complain, even when their lives are at risk. “A lot of our colleagues are afraid to cover [COVID-19], but they don’t express it to their editors,” says a journalist from the Quintana Roo Network of Journalists in Mexico who spoke anonymously out of fear of retaliation. That journalist told me there’s a sense that editors will say, “‘Behind you there are thousands of people wishing to have a job. You should feel like one of the lucky ones,’ when in fact they are telling you ‘Go, risk your life and bring us an article of 2,000 characters.’” Many journalists have largely stopped standing up to defend their rights—because why bother?

But for some journalists and journalism organizations, the pandemic has served as motivation to raise concerns instead of swallowing them.

Negotiating Work Conditions and Staying Safe

One thing that Latin American nations have in common is that “journalism has been considered an essential service, but it hasn’t been treated like one,” says Zuliana Lainez, senior vice president of IFJ.

Even in countries where journalists are more likely to be employed by media companies, such as Brazil, Uruguay, Chile, and Paraguay, their needs aren’t always taken care of. Lainez says that she has never before seen journalists experience “the level of stress there is now.” But media companies have been more worried about keeping their business afloat than about the safety of their staff and freelancers, she says. “Covering a pandemic is risky. What is a greater risk than losing your life if you are infected? So, you cannot send reporters out without risk insurance, but they are.”

Take Hernández, who works full-time for her newspaper. Because of her passion and commitment, she decided to keep working despite her pay cut. But she also realized she deserved to be protected by her newspaper. “The work that they ask of me is the work that I deliver,” she says.

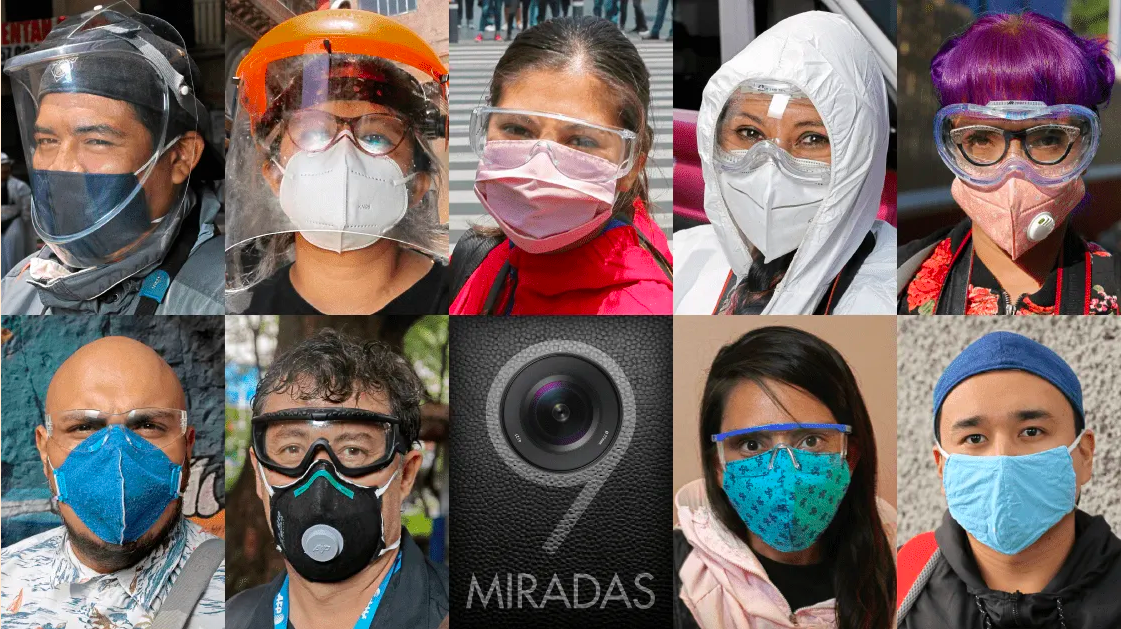

With that confidence in her value to the paper in mind, Hernández requested a coronavirus safety kit. The newspaper’s financial crisis meant that they could only give her 1,000 pesos ($46) to buy what she needed. But it was more than any of her coworkers received.

And it was more than many independent journalists get. Lainez says that journalists in the Andean area—Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, Colombia—and some parts of Central America, are particularly vulnerable because they tend to be freelancers. They “don’t have a company behind them, and they have continued to cover the pandemic from inside all the infectious sources—hospitals, markets, public spaces—while being solely responsible for their safety conditions.”

Such is the case for Marco Antonio Morán Huanaco, an independent journalist from Mazamari, Peru, who for 20 years has been responsible for paying for the airtime of his radio show Libertad de Expresión (Freedom of Speech) on Radio Integración. Advertising used to help him make ends meet, but after the pandemic struck and advertising was reduced, he started depending on his real estate job to continue the program. To stay safe, “honestly, I had to make my own masks,” he says. (Independent and freelance journalists worldwide can access support funds from the International Women’s Media Foundation or Rory Peck COVID-19 Hardship Fund. They can also review materials and resources from SembraMedia, the National Endowment for Democracy‘s grants and look for ongoing opportunities in the International Journalist’s Network website.) It can be daunting for journalists—staff or freelance—who can’t afford to lose their job or who don’t want to lose their air time or risk their independent news sites to approach an editor and demand better work conditions.

Outlets that hire freelance journalists still have an ethical obligation to protect those workers, says Andalusia Knoll, coordinator of the organization Frontline Freelance Mexico. But the journalists often don’t realize it, or don’t know how to ask for it. “You’re so afraid that you’re going to lose your [assignment] that you’re not even thinking about your own safety,” Knoll says.

Even before the pandemic, Frontline Freelance Mexico had been offering webinars and workshops to train freelance journalists on how to negotiate their contracts with editors and ask for the protections that they need to do their job, including hazard pay when appropriate. Knoll lives by her own advice: As a freelancer in the pandemic, “I have charged more than I normally charge because of the risk level,” she says. Freelancers shouldn’t have to fear that making these requests will ruin their relationships with editors or that in doing so they’ll come across as too demanding or rude, she says—it’s business, and publications should understand.

Still, it can be daunting for journalists—staff or freelance—who can’t afford to lose their job or who don’t want to lose their air time or risk their independent news sites to approach an editor and demand better work conditions. Lainez points out that the biggest collective lesson that journalists have learned in the past seven months is to stick together. “We need to let go of that history of individualism: ‘I compete with you to get to the story.’” That’s what journalists all over the region have started to do, by sharing safety tips, sources and information to aid their reporting, and even safety kits. Journalism organizations such as Artículo 19 (the Latin American branch of the British human rights organization Article 19), Frontline Freelance Mexico, and the international Committee to Protect Journalists are stepping up to provide journalists with free safety and ethical guidelines for the coverage of the pandemic.

As in the United States and elsewhere, journalists are working together to make sure as few people are exposed to the virus as possible. Early in the pandemic, the Mexican newspaper El Heraldo de Mexico sent almost everyone home and took strict measures to protect those working in the field. Daniel Ojeda, a photojournalist for the paper, says the trick to keep printing high-quality information was to work together.

For example, he worked on a story about how a Mexican Air Force plane transported COVID-19 medical supplies to different military-built hospitals across the country. Ojeda—who traveled with the plane to take the pictures—narrated the whole ordeal to the reporter at home and helped him to get the interviews from afar.

Reporting through the Barriers

Staying safe is not the only challenge for Latin American journalists during the pandemic. Too often, journalists trying to report on the science of the pandemic must contend with Latin American governments that discredit them; don’t publish reliable, accessible data; spread fake news; and often refuse to answer questions. Although this may sound familiar to U.S. journalists, the Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index shows such problems are even more pronounced in some Latin American countries.

Staying safe is not the only challenge for Latin American journalists during the pandemic. Too often, journalists trying to report on the science of the pandemic must contend with Latin American governments that discredit them; don’t publish reliable, accessible data; spread fake news; and often refuse to answer questions.

The IFJ, which has been tracking the information blockages, found that all the countries in the region have had problems with information access, says Lainez. For starters, Latin American governments have been pushing journalists to refer only to official sources—which in most cases means government sources—to report about coronavirus. Governments don’t want journalists reporting from the medical centers, cemeteries, or other hot spots that might show a different reality than the one they are officially portraying to the people. “No expert can give information on COVID-19. Not even the director of the health center. Only authorized people from the state,” says Morán Huanaco. Journalists get persecuted and stigmatized if they ask questions or inform the audience about these omissions of information. Venezuela and Peru have even detained some journalists for doing so, something Morán Huanaco experienced firsthand.

When Morán Huanaco heard about a possible first case of coronavirus in his home district of Mazamari, in central Peru, he talked to the medical director of the local hospital to confirm the news and published the story on his public Facebook page. The next day, the police arrested him—on charges of disturbing the public order—for posting the piece. He was released that same day, but not before the police took his picture for the files. The next day, that same picture was circulated as a press release to all the media in the country, claiming that “a citizen” had been detained for spreading fake news. “They didn’t even acknowledge his journalist status,” says Lainez. The National Association of Journalists in Peru spoke out against the chief of police for abuse of authority. According to Lainez, Morán Huanaco was the first journalist detained under disturbing-the-public-order charges in 10 years.

It’s even worse in Venezuela. “Venezuela is, at the moment, the Latin American country with the most arrested journalists in the framework of the pandemic,” says Lainez. Often, their families don’t know where they are for as long as two days.

In many Latin American countries, there is also a culture of refusing to answer to the press. In El Salvador, for example, government officials have started blocking journalists from their Twitter accounts. Even the government’s virtual press conferences offer little opportunity to ask questions. According to Lainez, journalists in the region typically have to send in their questions via WhatsApp an hour before the press conference begins, and follow-ups are banned. The more critical questions simply aren’t asked.

This is all happening as governments are spreading misinformation—long a problem in Latin America, though it was typically previously reserved for politics. Governments of Mexico, Venezuela, Brazil, and Nicaragua, to name a few, are spreading coronavirus misinformation and downplaying the pandemic. Authorities have even promoted the use of dangerous or ineffective treatments for COVID-19 (something that might also sound familiar to journalists in the U.S.).

Latin American science journalists know that there are no easy answers to deal with these types of misinformation. As a strategy to fight it, some pre-pandemic fact-checking sites such as Verificado, Ojo Público, and Agence France-Presse Fact Check have turned their efforts to COVID-19. Other efforts originated in the context of the pandemic, like COVIDconCIENCIA, El Surtidor’s Coronavirus en Paraguay and Salud con Lupa’s Comprueba.

Science Journalism’s Shaky Status in Latin America

Science journalism has long struggled to find its place in the Latin American region. A mapping of science journalists around the world conducted in 2012 by the London School of Economics received only 179 responses from journalists from 10 countries in the region. Luisa Massarani, SciDev.Net’s regional coordinator for Latin America and the Caribbean and also a collaborator on the mapping project, says that since then, science journalism has grown unequally across Latin America, although in-depth research is still needed to determine the reasons for these differences.

Countries like Mexico, Colombia, Argentina, Chile, and Brazil have been increasingly prioritizing science journalism in newsrooms and have created national networks of science journalists, but media companies in Paraguay and El Salvador, for example, still lack interest in covering science.

According to Will Monterroza, a freelance science journalist from El Salvador, the only science news in his country has historically been limited mostly to reprinted articles from international news agencies. During the pandemic, most Salvadoran outlets have covered the coronavirus from a political angle, tossing the science aside. (To confront the lack of science news in El Salvador, Monterroza launched a digital science journalism outlet, El informe news, in 2015. Since the pandemic began, he has been posting coronavirus stories and videos. He finances the site with his multimedia and teaching jobs.)

Yet some journalists see the coronavirus as an opportunity to bring the role of science in society to the fore. “The pandemic gave more visibility to the importance of science to combat the disease and of journalistic coverage of science and health issues. The fake news pandemic associated with the COVID-19 pandemic has also given visibility to the importance of quality scientific journalism,” Massarani says.

It has also given reporters new opportunities to connect with one another via virtual meetings, webinars, and workshops. For example, in May the Foro Hispanoamericano de Periodismo Científico, edición Covid-19 (Hispano-American Forum of Scientific Journalism, Covid-19 edition) brought together, via Zoom, journalists from Latin America, Spain, and the Caribbean. The forum also offered workshops focused on giving science journalists the necessary tools to improve their coverage of COVID-19, such as how to interpret and communicate contagion statistics or how to use Google’s advanced tools to find fake news and fact-check information.

Little by little, this pandemic has shown journalists from Latin America and other parts of the world how important they are to society. Hernández hopes this moment will drive journalists to take better care of themselves and demand the same from their publications. This is a scary time to be a journalist, but “this is a historic event,” she says, and she will do everything she can to keep covering it.

Myriam Vidal Valero is a freelance science journalist from Mexico City. She’s a member of the Red Mexicana de Periodistas de Ciencia. She loves photojournalism, reading books about the history of science, and reporting about the curiosities of the world. She has written stories for The New York Times, Science, ¿Cómo ves?, Muy Interesante, and Medscape, among others. She is also a recipient of a Rosalynn Carter Fellowship for Mental Health Journalism. Follow her on Twitter @myriam_vidalv.