Jon Mooallem is fascinated by the relationships between humans and other animals, a topic he explores in his 2013 book Wild Ones: A Sometimes Dismaying, Weirdly Reassuring Story About Looking at People Looking at Animals in America. Mooallem is a contributing writer to The New York Times Magazine, and a frequent contributor to other magazines and radio shows, including This American Life, Harper’s, and Wired, where for a short time he wrote a column called This Week in Wild Animals.

In researching Wild Ones, Mooallem came across a story that sounded too strange to be true: a plan to bring hippopotamus ranching to the bayous of Louisiana in the early 20th century. The hippos would solve two problems at once, proponents argued: They would provide a new source of protein for a nation in the midst of a meat shortage, and they’d gobble up invasive water hyacinth that was choking waterways and killing fish. The idea made it all the way to the U.S. Congress, which held a hearing on the matter in 1910.

Mooallem first told the story at Pop-Up Magazine in San Francisco in 2010. The story “American Hippopotamus” finally appeared in print in December 2013, in The Atavist. It turned out to be about more than just hippo ranching. It’s a story about a more idealistic time in our nation’s history and two men—spies and sworn enemies—who found a common cause in the hippopotamus scheme.

Here, Mooallem tells Greg Miller about how he researched this century-old story and tried to make its characters come to life. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

How did you come across this story?

How did you come across this story?

I started Wild Ones in the spring of 2010 and one of the first things I did was I got a little obsessed with this guy named William Temple Hornaday. He was a taxidermist turned conservationist in the early 1900s. I was reading this giant book he wrote called Our Vanishing Wildlife. It’s basically one big screed, but in the middle of it there’s this one detail where he says something like, “How stupid it is that Mr. Broussard thinks he needs to bring African animals to America to replace the ones we’ve annihilated?” I didn’t know what that meant, but then a little Googling brought me to the transcript of that Congressional hearing in 1910.

Reading through that document was just mind-blowing. They would say things like, “Why not bring zebras, they would make the plains so much more beautiful.” And, “Giraffes taste delicious and the leather is great, let’s put them in Arizona.” I found that all kind of amusing, but also the earnestness with which they were discussing it was kind of compelling. So from there I did a little more digging to find out who these guys were.

How did you go about that?

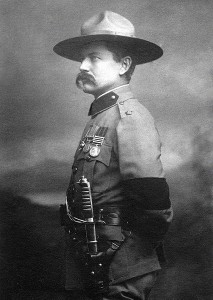

Well, the bigger context is I knew I had these two figures, Frederick Russell Burnham and Fritz Duquesne, who’d be central characters, and I had a third, Congressman Broussard, who would be a secondary character. So in three parallel paths I started trying to find as much as I could about each of them, hoping that I’d find points where their lives intersected. There’s not much about these fellows online, and really nothing about the hippos. In some ways that makes it extremely difficult, but in other ways it makes it kind of easy because when you find out about something, you make an effort to get it because you can’t afford to be picky. Every bit of relevant info became super precious. There’s not a lot of research I had that didn’t make it into the piece.

With Broussard, there’s an archive of his papers at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. I was in touch with an archivist there. The middle of the piece, where I describe what happens after the hearing when they’re strategizing about how to bring the idea back to Congress, that’s all culled from a folder of about a hundred of Broussard’s letters [the archivist] sent me.

I was able to figure out who Duquesne and Burnham were by basic Googling, but I didn’t get much further than that. Burnham had written two memoirs. At the time I only knew about one. It’s a rare book because he published it himself and just sent it to friends, but they had it in a special collection at Berkeley in the Bancroft Library. So I spent time there reading it. Eventually I just bought it online for like $200.

Burnham’s papers are in libraries at Stanford and Yale, and I spent a lot of time at Stanford reading through his archives. There’s no file folder with the hippo papers, just letters alphabetized by recipient, so I spent a lot of time reading a few letters for each one to get an idea of who this person was and whether he would likely be writing to them about this plan. I hired a graduate student at Yale to do some fishing in that archive to uncover anything that wasn’t at Stanford.

Another thing I did was search through newspaper archives for any mention of Burnham and Duquesne, or Broussard for that matter.

The last thing was Burnham’s family. I found one of his great-great-grandsons pretty late in the process. His name is Rod Atkinson, and he happens to be a researcher at the Library of Congress. He’d done a lot of research on his own time. He sent me a lot of things I didn’t have, but mostly he was really valuable as a person I could call up and say here’s what I’m finding, here’s what I make of it; and he could give me his perspective and maybe add some details here and there.

So was he your only living source?

Basically. There’s a woman named Maureen Ogle who wrote a book about the history of meat production and I talked to her a bit as well. But those are the only phone calls I made.

OK, so once you have all this material and it’s time to start writing, how did you decide how to structure it?

I actually didn’t know whether or not I had a story. I started out to tell the rise and fall of hippopotamus ranching and how it involved these people. In fact we don’t really know that much about that. I’d done all this research and I had a pretty detailed sense of these two characters and a somewhat detailed account of the hearing and what happened after. But I couldn’t explain it as anything dramatic because the hippo plan didn’t seem to end in any climactic way. It just didn’t get off the ground.

I called Evan Ratliffe [editor of The Atavist] and said, “I just don’t think it adds up to anything.” But in the course of that phone call we figured it all out together. What I’d been thinking was the entire story turned out to be the core of a much longer story. What we figured out was that the hippo thing was a climactic event, but it wasn’t a climactic event in the story of bringing hippos to America—it was a climactic event in the story of Burnham and Duquesne. So it became a double biography of these two guys where they’re going to come together in the middle for this hippo project and then diverge apart again.

The idea we came up with is you’d be following Burnham through the first half, with Duquesne as sort of a foil. And then in the second half, it’s more about Duquesne, who spirals out of control, while Burnham becomes a less interesting character because he kind of just keeps on keeping on. Once we conceived of it that way, it literally all just clicked into place.

What was the most challenging aspect of the actual writing?

Just dealing with the fact that it’s historical and there’s not as much research available as there would be for a contemporary story. I would inevitably come to points where I just didn’t know what happened. It became a challenge of not making things up by inadvertently speculating about what they did or what their intentions were. There was a lot of writing around the uncertainty in places.

What’s an example?

There are all these letters about what they’re going to do after the hearing and how they’re going to get this thing off the ground. And then suddenly this guy Eliot Lord shows up and he’s writing letters to all these guys too. And he’s important because he says he can bring all these wealthy people onboard, but he’s also ridiculous, kind of a snake oil salesman, so they’re getting annoyed with him. I couldn’t leave him out because he’s a really interesting character and he shook up the whole story at that moment, but I also didn’t really know anything about him or how he got involved. So I say in the piece something like, it’s not clear if anyone actually invited him to this conversation, but regardless here he was.

What did you do to try to make the characters come alive, given that, well, they’re dead and you never met them?

That was a really fun part. There was this guy W.N. Irwin from the agriculture department who testified at the Congressional hearings. There wasn’t a ton about him and I guess that’s a place where I maybe took some liberties. I just got such a clear sense of this guy from reading the very little that I had. He seemed like a giant dweeb. He was obsessed with why people don’t eat turkey eggs–they’re so healthy, they last a long time. So I tried to imbue the information I had with a kind of personality. This guy is kind of a geek so I’m going to describe him in a geeky way. He didn’t just write that turkey eggs were better, maybe he kept insisting that turkey eggs were better. I was inferring a lot from what he’d written, but everything I wrote can be sourced back to something.

One thing I like about this is how in places you sort of take a step back from the story and offer some interpretation, like the way you describe the rivalry between Duquesne and Burnham. You say: Theirs was an old-fashioned kind of rivalry … nothing as vulgar as hatred. It involved a bizarre kind of honor. How do you know where and how to do that?

Sometimes you have all this information and it just sort of feels like information, you’re not sure what to make of it. And it’s the same process for the reader who’s trying to absorb it, so you have to try to put a frame around this stuff. In this case, you have these guys writing letters back and forth, and they believe in totally different things and they’re trying to kill each other, but they talk in glowing terms about the skills of the other guy. I had all that information but I didn’t know how to characterize it. But then I realized this is that sort of old-fashioned thing, like Sherlock Holmes and Moriarty: They need each other. I suddenly understood it better myself. It’s funny you mention that one in particular because I remember that being an ah-ha moment.

When did you decide to include an author’s note at the top of the piece, and what was the rationale for that?

That came pretty late. Charlie Homans, the executive editor, was top-editing the piece and I think it was his idea. The idea was that we needed almost like a nut graf to say this is a story about two spies, it’s not just about hippopotamuses. At first I resisted, because I’ve never really understood the purpose of that trope of I’m going to tell you a story about such and such. They only make sense to someone who’s already read the story.

So I wrote it, but it wasn’t really working. Then we realized there was a bigger point to it, which was to situate you in the world of the piece, to prepare you that you’re going to be reading some things that sound absurd, but they’re true. Then it started to seem more important to me. And the tone changed from serious to a little more oddball. Evan actually sent me a clip of the opening scene from the Big Lebowski, the prologue where Sam Elliot comes on and is talking about the Dude. It’s the only time in my life that an editor sent me a clip from the Big Lebowski and told me to make it sound like that, but he was absolutely right.

*

*

Greg Miller is a senior writer at Wired. He writes about biological, behavioral, and social science and co-founded Map Lab, Wired‘s blog about maps and mapmaking. Before joining Wired in 2013, Greg was the San Francisco news correspondent for Science magazine. He was part of a team of writers who won an award from the National Academies in 2013 for a special issue of Science devoted to research on human conflict. Follow Greg on Twitter @dosmonos.