It’s hard to make a character seem vivid and real on the page, even if you spend hours or days with your subject. But in his 2011 book The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools, and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth, which profiles pioneering naturalists and specimen collectors, writer Richard Conniff managed to do this without exchanging a single word with his characters. That’s because every major character in the book has been dead for decades or centuries, making his ability to bring them to life on the page all the more miraculous.

Now, Conniff is working on his eighth book, this one about the history of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, and he is facing similar challenges: A living character doesn’t show up in the book until more than three-quarters of the way through. (Disclosure: I know this because I work for Conniff and the Peabody Museum as an assistant on this book project).

In an empty classroom adjacent to the Peabody Museum in New Haven, Connecticut, Conniff and I discussed his techniques for raising the dead, including how he uncovers the most telling details about long-gone characters. We also touched on how he keeps track of voluminous historical research materials. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Much of the action in The Species Seekers took place in Europe. Where did you conduct the bulk of your research?

Yeah. It was actually wonderful. I went to the Linnean Society, in London, which is in the same complex of buildings in which Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection was introduced to the world in 1858. I asked to see Alfred Russell Wallace’s field notes from when he was in what is now Indonesia, and they just handed me a worn, leather-bound volume, and I could sit there and read as long as I wanted. They didn’t even have me wear white gloves or any of those things that museums elsewhere do. They just allowed me to work, and it was wonderful. Honestly, having the documents in your hand is like being able to communicate directly with the people that you’re writing about.

Then I went to Paris, because I wanted to write about the Comte de Buffon, who was an early naturalist, very influential, and I went to visit his place down in Burgundy. And I went up to Uppsala, in Sweden, to visit [botanist Carl] Linnaeus’s stomping grounds. At all those places, you get to see how people lived. You get a sense of the scale of their lives, how close Linnaeus was to the university where he worked, and how long a walk it was out to his summer house outside the city—all that kind of stuff. So I think that’s really important to being able to bring people back to life on the page.

When you’re combing through old documents, what do you look for to help sketch out a character?

I often look for things that aren’t necessarily what would strike a specialist in the field as being the most relevant to the work. A lot of what I wrote in The Species Seekers was about how people reacted to the news of Darwinian evolution and what a terrific, wrenching experience it was for them, especially for people who are deeply religious.

Puzzling over the question of how fossil animals had gotten buried in the Earth, to a depth that seemed to translate to millions of years, [19th-century naturalist Philip Henry] Gosse concluded, in effect, that God had hidden them there like Easter eggs, to be discovered by his happy children. At the moment of Creation, Gosse wrote, “the Creator had before his mind a projection of the whole life-history of the globe.” Then he called that globe into being not at its beginning, but at some random moment in its history…. Not surprisingly (except to Gosse himself), the world, both religious and atheist, Catastrophist and Uniformitarian, drunk and sober, responded with derision. (pp. 272–73)

In this book, about the Peabody Museum, I’m doing the same sort of thing with James Dwight Dana, who was corresponding across the Atlantic with Darwin from the 1840s on, and who was really, deeply religious. And he suffered a psychological breakdown which seemed to coincide with the publication of On the Origin of Species. Even though Darwin sent him a personal copy, a gift copy—one of the first two in this country—he couldn’t bring himself to read it for three or four years. And those kinds of very telling details are what make a character live, for me.

Do you have a systematic way of finding those details?

I go through a lot of material, and I really do look for things. You know, there’s something that somebody told me: If there’s something that you need to tell your friends about at the end of the day, that better be in the book. Because that’s what people want to hear. They want to know about those curious, quirky kinds of things that really engage you in the life as it was lived. So, how do I find those things? I saw this great quote recently. It said that a writer is like a pig hunting for truffles. You know, you have to have a certain nose for it, but once you’ve got that, you become addicted to snuffling out those details. That’s what I do.

The Species Seekers includes some characters who—unlike Darwin—seem to have been forgotten by history. How do you decide which historical characters to include?

I like people with interesting lives. It’s not possible to include every interesting life if it isn’t relevant to your story. But if you’re scrounging around long enough, and you’re searching for those truffles, then sooner or later you come up with enough of them about one person that he or she seems to fit in the story. There’s one character in particular from The Species Seekers [Thomas Edward], from the coast of Scotland. He tried to kill himself by walking into the water and drowning himself, but then he saw a beautiful bird as he was going in and started chasing the bird for the next 20 minutes, and he forgot that he wanted to kill himself. That guy just leaped out at me as a character.

When he got tired [while collecting at night], he often bedded down in the shelter of rocks, graveyards, or abandoned buildings. Sometimes he tucked himself feet first into a fox hole or badger hole in a sandy bank. Once, a badger came home and, finding him there, bared its teeth. With regret, Edward shot it (he did not like wasting ammunition). (p. 194)

I’m not even sure that he really belonged in the book, because I don’t think he discovered species. But he embodied this kind of amateur enthusiasm—he was a shoemaker, I think—that existed for natural history in the first half of the 19th century, and a little bit beyond there. And he just sort of worked his way into the book.

One of the benefits of writing about scientists is that they often carry out their debates in public forums, in published journals. But The Species Seekers includes many conflicts and rivalries that only play out in private. Can you talk about how you dug up some of those stories?

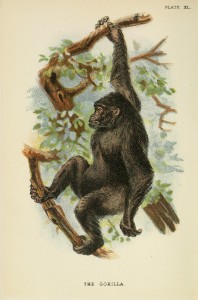

I’m thinking of Paul Du Chaillu, who came out of West Africa in the 1850s. He was French, and he had brought back a number of specimens, including 20 [dead] gorillas. And gorillas were really not known to the general public then, although they had been described scientifically. He made them a sensation.

And it was just at the time that Darwin’s Origin of Species came out. When he got to London, he was feted as a hero for about a week. Then the most virulent attack began, in the press, and it went on for months, in the most personal terms. He spat in somebody’s face at one point, after an ugly confrontation at a speech. And the virulence that people brought to that debate probably had partly to do with coming to terms with the idea of evolution, and with suddenly having the reality of it presented to you in the form of a stuffed gorilla, and the resemblance to humans in the hands, and so on. But there was also this subtext going on, these letters going back and forth across the Atlantic, about how Du Chaillu was in fact of mixed race. His father had come from an island in the Indian Ocean and had a slave there, I think, and they’d had this child there together, and this was Paul Du Chaillu. And a guy in Philadelphia who was interested in skulls and race and intelligence said that Du Chaillu had a skull of “dubious origin,” or something like that. So there was this whole racial subtext that was carried on in correspondence, but never in public. That’s the ideal from a storyteller’s point of view.

How did you learn about and track down that kind of correspondence?

In this case, I think someone had told the story, but he had told it in an obscure academic journal. And that’s also a wonderful thing for a writer: Scientists often tell great stories, but they tell them really badly, and they tell them in these journals that nobody reads. And so to go back there and to see what they were talking about, and then research it a little further, is often payday. Honestly, writing natural history, there are often wonderful things in scientific articles about species discoveries, or about any scientific phenomenon at all, any behavior. But those wonderful things are often buried, like in the fourth paragraph of the discussion. They’re lost. And you can go treasure hunting, you can go snuffling around for those truffles there, and come up with wonderful things. I often feel badly for the scientists, because they’re not telling their own stories right.

As you’re building up a story, how do you keep track of the details you want to use?

Okay, this is not going to sound very orderly. I used to be a lot more orderly when I was starting out. I used to diagram everything. I even used file cards in the beginning, and I had all my quotes and all my facts on file cards. But that is not how I work now. I wing it, basically. As I’m reading something, if it’s good, and I know it’s good, and I like it, I just write it, right there. I don’t care where it fits in, I just write it on the spot. Later on, when I’ve got a context going, I pull it up out of this bottomless bog of material that I call the scrap heap, and I bring it over to the place that it is going to be used. And then I rewrite it into the context. If you’ve got Wallace’s journal in your hand, and you’re reading it, then everything is raw, and fresh, and you feel the emotions. And so it’s much better to write it then, and to have all that material in one place—and then later on, when you look at it with a somewhat more mature perspective, you may change it, but at least you’ve gotten it down on paper to start with.

So it’s literally just one long Word document where you just have these little snippets that you’ve written down.

Uh-huh. I know this is bad. I know there are better ways to do this. Eh, what can I say. It’s what I do. It works.

This kind of research involves lots of sources, probably more than for a non-historical book. How do you keep track of where your material comes from?

To preserve your trail, you have to download a lot of the stuff. Or, I use comments a lot, and I write down what the source was. It’s not only useful for fact-checkers or researchers, it’s useful for you when you go back to find out whether you really understood things, the way you wrote it, or whether there’s some other context that you missed. You just go to that comment, you go back to the original document, and then you can read it again and say, “Oh yeah, I got that right.” Or, somebody criticizes it, or comments, and you can go back and say, “No, screw you, I’m right.”

What advice would you give someone thinking of writing a book based mostly on historical characters—especially someone who hasn’t done anything like this before?

It’s a huge undertaking. And I think if I were starting out, and tried to do this, I would fall all over myself. Because you just have lots of stuff up in the air at the same time. And you have to pull it all together, and somehow make sense of it, and that’s just not easy to do. In a way, I think that the Peabody book and The Species Seekers book suffer because there are so many characters. And it’s better to focus on one character who’s in a conflict of some sort—that is, one character who faces opposition. People who were cut out by society, who were cut out by science, who weren’t allowed to do what they wanted to do … those are good stories.

The other thing I would say is to look close at home. When I was in my 30s, I went back to this house that we owned in Connecticut. And there was this photograph, a postcard that showed a cart with $9,000 worth of ivory tusks in the back. I started to poke around, and I found out that what I had always taken for a broken-down green shed had been an ivory-bleaching shed in the neighborhood, and that the town that I was living in had been the major consumer of ivory in the Western Hemisphere for much of the 19th and early 20th century. And so that was kind of a great story, close to home. I didn’t have to go anywhere to write it. I was traveling all over the place for other stories, and here was this thing that was just in my own lap, right here. So that’s good to find stuff like that. Look for a great character, look for a difficult situation, look for something near you.

Geoffrey Giller is a TON fellow sponsored by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. He is a freelance writer and photographer and a recent graduate of the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Science, where he studied frogs and water contamination. He has written for Scientific American, Audubon, and other publications. A lover of all amphibians, Geoffrey especially adores salamanders and hopes one day to meet a hellbender in the wild. You can follow him on Twitter @GeoffreyGiller and see some of his photography at his website.