The following story diagram—or Storygram—annotates an award-winning story to shed light on what makes some of the best science writing so outstanding. The Storygram series is a joint project of The Open Notebook and the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing. It is supported in part by a grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. This Storygram is co-published at the CASW Showcase.

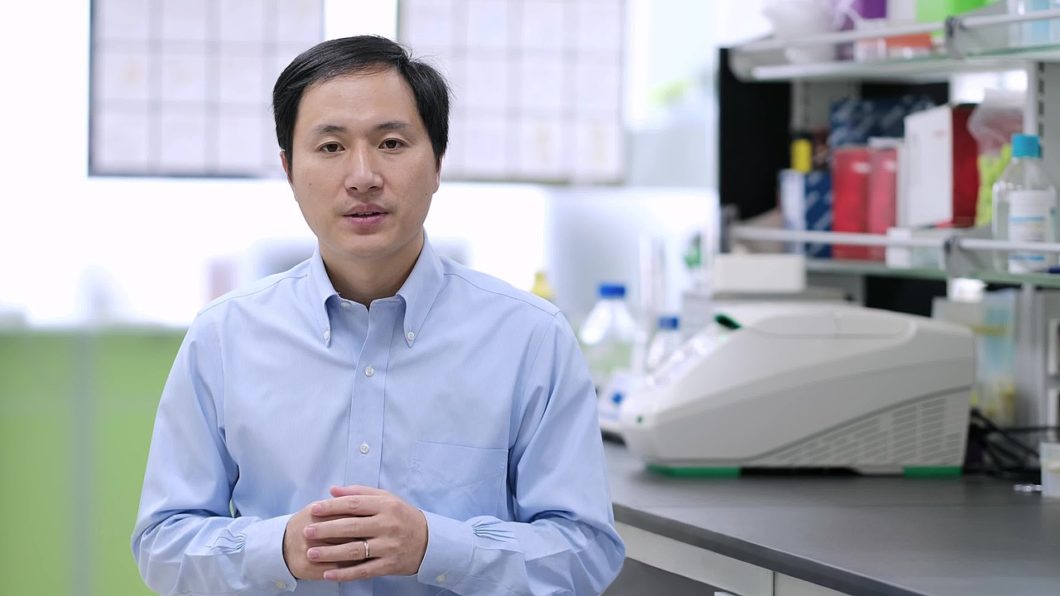

Chinese scientist He Jiankui announced in November 2018 that that he helped make the world’s first genetically edited babies using the gene-editing tool CRISPR. MIT Technology Review reporter Antonio Regalado learned details about the controversial experiment from a Chinese-clinical-trials registry. His story, “Exclusive: Chinese Scientists Are Creating CRISPR Babies,” was published on November 25, 2018. In the Storygram annotation below, I analyze key aspects of Regalado’s story that contribute to its impact. (In a separate Storygram , I also analyze Marilynn Marchione’s Associated Press story reporting on the birth of the gene-edited twins.)

Story Annotation

“Exclusive: Chinese Scientists Are Creating CRISPR Babies”

A daring effort is under way to create the first children whose DNA has been tailored using gene editing.

By Antonio Regalado, MIT Technology Review

Published November 25, 2018

(Reprinted with permission)

(Go back to our CRISPR babies splash page.)

When Chinese researchers first edited the genes of a human embryo in a lab dish in 2015, it sparked global outcry and pleas from scientists not to make a baby using the technology, at least for the present.This lede contains key background information, which sets the reader up perfectly for the current news.

It was the invention of a powerful gene-editing tool, CRISPR, which is cheap and easy to deploy, that made the birth of humans genetically modified in an in vitro fertilization (IVF) center a theoretical possibility.

Now, it appears it may already be happening.

According to Chinese medical documents posted online this month (here and here),Right up front, Regalado shows his work, the source of the news. a team at the Southern University of Science and Technology, in Shenzhen, has been recruiting couples in an effort to create the first gene-edited babies.And here is the news. It’s a powerful opening. They planned to eliminate a gene called CCR5 in hopes of rendering the offspring resistant to HIV, smallpox, and cholera.

The clinical trial documents describe a study in which CRISPR is employed to modify human embryos before they are transferred into women’s uteruses.

The scientist behind the effort, He Jiankui, did not reply to a list of questions about whether the undertaking had produced a live birth. Reached by telephone, he declined to comment. Regalado is transparent, right up front, about his efforts to reach He; in a story on such a controversial subject, it’s important to “show your work” in this way. By citing He’s lack of comment, this paragraph also signals that the reporting may leave unanswered questions.

However, data submitted as part of the trial listing shows that genetic tests have been carried out on fetuses as late as 24 weeks, or six months. It’s not known if those pregnancies were terminated, carried to term, or are ongoing.

[After this story was published, the Associated Press reported that according to He, one couple in the trial gave birth to twin girls this month, though the agency wasn’t able to confirm his claim independently. He also released a promotional video about his project.]

The birth of the first genetically tailored humansGreat word choice—original and descriptive. would be a stunning medical achievement,This phrase suggests the reward, the why for the experiment. for both He and China. But it will prove controversial, too. Where some see a new form of medicine that eliminates genetic disease, others see a slippery slope to enhancements, designer babies, and a new form of eugenics.Here, Regalado gets us quickly to the ethical murkiness of the procedure.

“In this ever more competitive global pursuit of applications for gene editing, we hope to be a stand-out,” He and his team wrote in an ethics statement they submitted last year. They predicted their innovation “will surpass” the invention of in vitro fertilization,These statements provide powerful supporting evidence for the idea that scientific firsts are the goal here. whose developer was awarded a Nobel Prize in 2010.

Gene-editing summit

The claim that China has already made genetically altered humans comes just as the world’s leading experts are jetting into Hong Kong for the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing.

The purpose of the international meeting is to help determine whether humans should begin to genetically modify themselves,I love the provocative phrasing here—we are doing this to ourselves. and if so, how. That purpose now appears to have been preempted by the actions of He, an elite biologist recruited back to China from the US as part of its “Thousand Talents Plan.”

The technology is ethically charged because changes to an embryo would be inherited by future generations and could eventually affect the entire gene pool. “We have never done anything that will change the genes of the human race, and we have never done anything that will have effects that will go on through the generations,” David Baltimore,A strong and straightforward quote that serves as a cautionary counterpoint to He’s statements above. a biologist and former president of the California Institute of Technology, who chairs the international summit proceedings, said in a pre-recorded message ahead of the event, which begins Tuesday, November 27.

It appears the organizers of the summit were also kept in the dark about He’s plans.Another nod to the secretiveness of the whole endeavor.

Regret and concern

The genetic editing of a speck-size human embryo carries significant risks, including the risks of introducing unwanted mutations or yielding a baby whose body is composed of some edited and some unedited cells.It’s good to spell out what the potential risks are, on different scales. There are risks to the babies themselves, in addition to the big scary risk of changing generations of humankind. Data on the Chinese trial site indicate that one of the fetuses is a “mosaic” of cells that had been edited in different ways.

If you’re enjoying this Storygram, also check out two resources that partly inspired this project: the Nieman Storyboard‘s Annotation Tuesday! series and Holly Stocking’s The New York Times Reader: Science & Technology.

A gene-editing scientist, Fyodor Urnov, associate director of the Altius Institute for Biomedical Sciences, a nonprofit in Seattle, reviewed the Chinese documents and said that, while incomplete, they do show that “this effort aims to produce a human” with altered genes.This quote shows Regalado’s diligence in getting an outside expert opinion on the documentation itself—remember that the reporter doesn’t know yet that the babies have been born.

Urnov called the undertaking cause for “regret and concern over the fact that gene editing—a powerful and useful technique—was put to use in a setting where it was unnecessary.”Another strong quote, this time to introduce the idea that the risky experiment was done without the justification of medical benefit. Indeed, studies are already under way to edit the same gene in the bodies of adults with HIV. “It is a hard-to-explain foray into human germ-line genetic engineering that may overshadow in the mind of the public a decade of progress in gene editing of adults and children to treat existing disease,” he says.Yet another strong quote that raises the possibility that the public’s trust in science may be at risk. Regalado does a great job using expert voices to lay out the reasons why many experts oppose gene editing in human embryos.

Big project

In a scientific presentation in 2017 at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, which is posted to YouTube, He described a very large series of preliminary experiments on mice, monkeys, and more than 300 human embryos. One risk of CRISPR is that it can introduce accidental or “off target” mutations. But He claimed he found few or no unwanted changes in the test embryos.Using the word “’claimed”’ suggests there is no independent verification.

He is also the chairman and founder of a DNA sequencing company called Direct Genomics. A new breed of biotech companies could ultimately reap a windfall should the new methods of conferring health benefits on children be widely employed.Important context about the potential financial conflict of interest—that a money-making venture might outweigh concern for scientific consensus and for families involved in the experimentation.

According to the clinical trial plan, genetic measurements would be carried out on embryos and would continue during pregnancy to check on the status of the fetuses. During his 2017 presentation, He acknowledged that if the first CRISPR baby were unhealthy, it could prove a disaster.

“We should do this slow and cautious, since a single case of failure could kill the whole field,” he said.

A listing describing the study was posted in November, but other trial documents are dated as early as March of 2017. That was only a month after the National Academy of Sciences in the US gave guarded support for gene-edited babies, although only if they could be created safely and under strict oversight.This suggests that in taking this step, the Chinese researcher is not heeding scientific warnings.

Currently, using a genetically engineered embryo to establish a pregnancy would be illegal in much of Europe and prohibited in the United States. It is also prohibited in China under a 2003 ministerial guidance to IVF clinics. It is not clear if He got special permission or disregarded the guidance, which may not have the force of law.I love the plain statement here. We don’t really know how He got around his own country’s regulations.

Public opinion

In recent weeks, He has begun an active outreach campaign, speaking to ethics advisors, commissioning an opinion poll in China, and hiring an American public-relations professional, Ryan Ferrell.

“My sense is that the groundwork for future self-justification is getting laid,” says Benjamin Hurlbut, a bioethicist from Arizona State University who will attend the Hong Kong summit.

The new opinion poll, which was carried out by Sun Yat-Sen University, found wide support for gene editing among the sampled 4,700 Chinese, including a group of respondents who were HIV positive. More than 60% favored legalizing edited children if the objective was to treat or prevent disease. (Polls by the Pew Research Center have found similar levels support in the US for gene editing.)Kudos for finding this really interesting information. It’s one thing to have consensus among scientists and input from ethicists, but what does the public think?

He’s choice to edit the gene called CCR5 could prove controversial as well. People without working copies of the gene are believed to be immune or highly resistant to infection by HIV. In order to mimic the same result in embryos, however, He’s team has been using CRISPR to mutate otherwise normal embryos to damage the CCR5 gene.This is a crisp and concise description of the science.

The attempt to create children protected from HIV also falls into an ethical gray zone between treatment and enhancement. That is because the procedure does not appear to cure any disease or disorder in the embryo, but instead attempts to create a health advantage, much as a vaccine protects against chicken pox.

For the HIV study, doctors and AIDS groups recruited Chinese couples in which the man was HIV positive. The infection has been a growing problem in China.

So far, experts have mostly agreed that gene editing shouldn’t be used to make “designer babies” whose physical looks or personality has been changed.

He appeared to anticipate the concerns his study could provoke. “I support gene editing for the treatment and prevention of disease,” He posted in November to the social media site WeChat, “but not for enhancement or improving I.Q., which is not beneficial to society.”It’s impressive how often He, the Chinese’s scientist, is quoted even though the reporter didn’t get access to him directly. Each quote is carefully sourced.

Still, removing the CCR5 gene to create HIV resistance may not present a particularly strong reason to alter a baby’s heredity. There are easier, less expensive ways to prevent HIV infection. Also, editing embryos during an IVF procedure would be costly, high-tech, and likely to remain inaccessible in many poor regions of the world where HIV is rampant.Regalado succinctly lays out these key medical arguments—that experimental approaches are considered more favorably if they’re addressing an unmet need, and that access is also important. This paragraph provides essential context for readers, helping explain why many experts rejected He’s justification for this research.

A person who knows He said his scientific ambitions appear to be in line with prevailing social attitudes in China, including the idea that the larger communal good transcends individual ethics and even international guidelines.An interesting point here—that cultural differences may play a role in how ethically questionable procedures are viewed. Also note that this is an anonymous source.

Behind the Chinese trial also lies some bold thinking about how evolution can be shaped by science. While the natural mutation that disables CCR5 is relatively common in parts of Northern Europe, it is not found in China. The distribution of the genetic trait around the world—in some populations but not in others—highlights how genetic engineering might be used to pick the most useful inventions discovered by evolution over the eons in different locations and bring them together in tomorrow’s children.

Such thinking could, in the future, yield people who have only the luckiest genes and never suffer Alzheimer’s, heart disease, or certain infections.This seems fair, to include the rosiest possible future of this work; that this may be aspirational science at work.

The text of an academic website that He maintains shows that he sees the technology in the same historic, and transformative, terms. “For billions of years, life progressed according to Darwin’s theory of evolution,” it states. More recently, industrialization has changed the environment in radical ways posing a “great challenge” that humanity can meet with “powerful tools to control evolution.”

It concludes: “By correcting the disease genes … we human[s] can better live in the fast-changing environment.”

Note: This story was updated after publication to include claims by He Jiankui that the trial had produced live births.

(Go back to our CRISPR babies splash page.)

Jill U. Adams writes a health column for The Washington Post and is a contributor to The Science Writers’ Handbook. She covers health, psychology, mental health, and education for publications such as Spectrum, The Scientist, and Nature. She reported on the science and policy questions concerning human gene editing for CQ Researcher in 2015. Jill lives in upstate New York and tweets as @juadams.