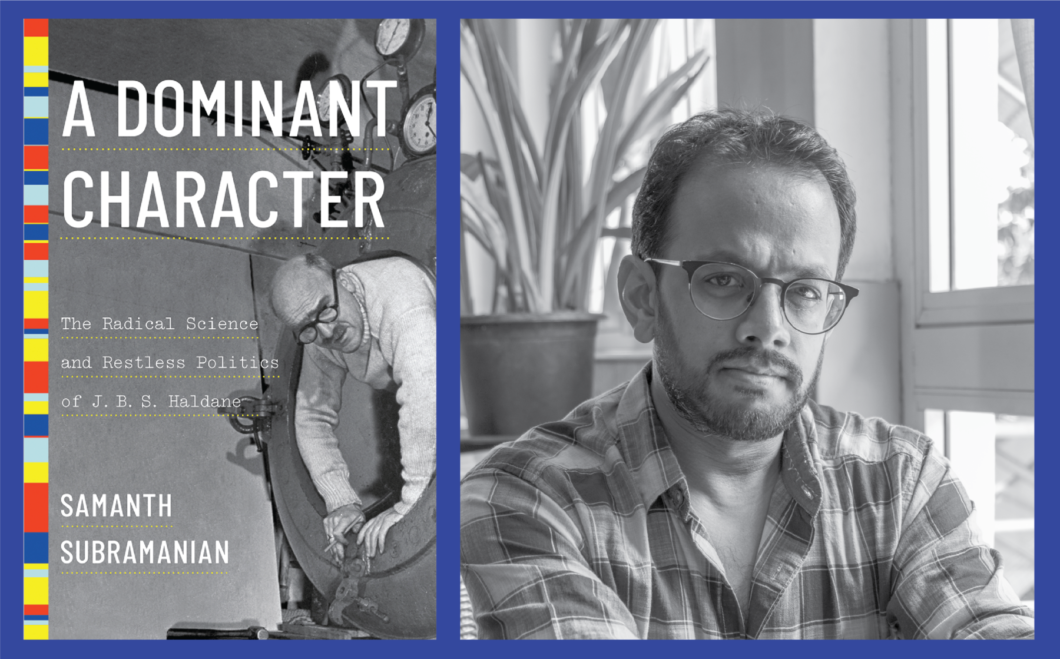

In the past four years, Samanth Subramanian has pored over thousands of archival documents in his attempt to get inside the head of a man who was once described as “the last man who might know all there was to be known.” In his latest book, A Dominant Character: The Radical Science and Restless Politics of J. B. S. Haldane, Subramanian brings that attempt to its fruition.

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane, the subject of Subramanian’s book, lived a boisterous life by any measure. As a boy growing up in England, he was a guinea pig for his scientist father. As a young man, Haldane served in World War I, writing papers from the trenches on the mechanism of genetic linkage. He hung out with Martha Gellhorn and Ernest Hemingway during the Spanish Civil War and nearly got them killed. As a scientist, he often inflicted pain on himself, inhaling noxious gases and drinking hydrochloric acid. He wrote, at long lengths, about science and politics for newspapers and magazines and filled town halls with his speeches. He was also a staunch Communist, to the point that the British intelligence agency MI5 surveilled him for 20 years, thinking he might be a spy. At the age of 65, he packed his bags and moved continents to restart his career in India. His life, as Subramanian puts it, “was stocked with enough danger and drama for a dozen ordinary humans.”

In A Dominant Character, Subramanian not only brings alive a captivating, larger-than-life story of this eccentric, passionate, and deeply flawed character, but also tells a broader story about the twinning of science and politics. “In the past years, as we’ve witnessed deliberate assaults on fact and truth, … the need for scientists to find their voice has grown even more urgent,” writes Subramanian. In that sense, Haldane’s story is ripe for rediscovery.

Here, Subramanian tells Pratik Pawar about his research process for this book, the challenges he encountered in biographical writing, and how he managed to turn them around to create a vivid narrative story. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

What was your research process like for this book, given that most of it involved digging through archival material?

I started my research for this book in 2015, and it was around 2016 that I actively started consulting the archives. It was the first time I’d ever done archival research of this kind, and so I had to ask people who’ve done this before quite extensively for tips on what to do in the archives. I think the most important tip I got was from the historian Srinath Raghavan, who said take a camera or take your phone into the archive. If you see a document and you are sure that you want to hold on to it, to consult it later, take a photo of it. If you see a document and you’re unsure whether you need it or not, take a photo of it. If you see a document and you think you will not have any need for it, take a photo of it anyway, which was great advice because that way you get to take the archives home with you in a sense and consult them at your leisure.

But very soon I realized that my usual method of research and writing [that] I apply in journalism, which is that you do all your interviews and research first and then once you think you’re mostly done, you sit down and start writing, I realized that would be quite fruitless in this particular case because there are so many papers. By the time I got done with reading all of them and assimilating them, and maybe re-reading some of them and taking notes and organizing them, years would have passed. So I was wondering what ought to be done in a situation like this. This was when I got a second piece of advice from another historian, Alex von Tunzelmann. She said, Listen, what you should do is when you think you have a fair measure of reading done, you should start writing. Please start writing the initial chapter, start structuring your book. Do all of these things because that’s the only way you will know how to read in a smarter way. By which she meant, I think, that when you go to an archive and you see a document, you will know quite clearly where it fits into the larger scheme of things. So that was a very good piece of advice and I took that to heart and started writing. So the majority of this book was written even as I was doing research, which is an odd way to do it if you’re a journalist, but apparently, this is a sensible way to do it if you are a historian or a biographer.

Did you have a set structure or a framework of how you wanted to tell this story? And did that evolve as you went about your process of researching and writing the book?

Quite early on in the process, I had what I think of as the big turning point or the linchpin of the book, what is popularly known as the Lysenko affair. This is the episode in 1948 when Haldane was called upon [by the BBC] to either defend or criticize Trofim Lysenko. Lysenko was an agricultural scientist in the Soviet Union who had somehow distorted the science of genetics completely and was claiming things about the science of genetics that were patently untrue. Some of them went against Haldane’s own work and findings and so Haldane was called upon to criticize this. But at that crucial moment, Haldane decided, for the first and perhaps only time in his life, to be politically loyal [towards the Communist party, and by extension the Soviet Union], rather than to be staunch in a manner of scientific integrity.

“In journalism, typically, the big advantage, or the big draw for me, is that I can go and meet people and go places and see things and describe them in a way that makes it come alive in near cinematic detail for the reader…. With archival research, I sensed from the beginning that that was going to be difficult because, obviously, you are not seeing anything or experiencing anything.”

Quite early on, I realized this was a very interesting inflection point in Haldane’s career. It was a culmination of all the things he had been thinking about and had experienced over the course of the last 50-odd years and I thought it was a good lens to tell the story through. So I knew that quite early, and the structure flowed from there in one sense. There’s a big prologue about the Lysenko affair and then the book is roughly chronological, and I knew that I wanted to preserve that structure. There was another thing that surprised me as I was going through this book. I’ve written two other books before this, and they have what you might call more orthodox chapters. This book doesn’t have any chapters, it only has five big sections. That was something I came to decide only as I was writing the book and researching it, because I figured that the flow of the book works a lot better if you treat it as one, almost-continuous narrative.

How was biographical writing different from your other journalism work, which involves reportage and talking to people? Were there any challenges specific to this form?

The primary challenge, which is also the reason [why] I embarked on this project in the first place, was to make a biography that is based purely on archival research and to make it nearly as vivid as a piece of journalistic writing can be. So in journalism, typically, the big advantage, or the big draw for me, is that I can go and meet people and go places and see things and describe them in a way that makes it come alive in near cinematic detail for the reader. It’s a classic trope of narrative nonfiction that you have scenes and characters and so on.

With archival research, I sensed from the beginning that that was going to be difficult because, obviously, you are not seeing anything or experiencing anything. But that was a challenge in a sense, and it was quite an enjoyable challenge because the way to do that then was to look for sources that were descriptive in themselves, so that you could incorporate those details into the biography and make it read in a more vivid manner. So this influenced a lot of what I read. For example, when there were letters of Haldane’s, or diary entries of Haldane’s, or whatever it may be, that were very descriptive, I would pay particular attention to those. I would borrow those details and incorporate them into my book.

And secondarily, it made me rely a lot on alternate sources, sources that may not have anything to do with Haldane himself, but that were written by people who were experiencing the same thing that Haldane was experiencing. One example here is Haldane’s time in the First World War, in the trenches in northeastern France, where Haldane himself wrote a little bit about it in his letters, but the broader picture of what was happening in the war was provided to me by so much else that has been written about that particular segment of the war already. So I directed my research in a particular way to find these specific kinds of details. And initially it was a challenge, but it was also an opportunity. I’ve never done anything like this before, and it made me realize the possibilities that come with this kind of genre of nonfiction.

Given the enormity of archival material that is available about a public figure like Haldane, how did you figure out what should go in the book and what should be left on the cutting room floor?

A lot of this was dictated by the structure, and by what felt important in that particular moment and what felt like a natural thing to include, when I was actually in the process of writing the book—by which I mean, when I was on my Microsoft Word document, literally typing the words of the book. So to do this, you have to do a couple of things. One is you have to be quite organized about your material so that you always know what you have.

So let’s assume there’s a particular segment of the book that I’m writing—let’s talk about the Spanish Civil War section. The Spanish Civil War section takes up 15 to 20 pages in the book. So before I would start writing that, I would go through all the material that I have pertaining to the Spanish Civil War, and I would take new notes on what is important, what I think is interesting, what can be left out. So within the Spanish Civil War folder, there would be little notepad files in which I will note, Okay, on page 22 of this document, there are some interesting things; in this book excerpt, there are some details that can be used to make this more vivid; in this folder, there are some letters that Haldane wrote from Spain, that kind of thing. And with that notepad file open in front of me, I would then start writing and that would provide me a scaffold of details to put through. And if I ever had any doubts about what the original sources actually said, I could then call them up quite easily based on that one notepad file. So a lot of it is just plotting it in that sense.

I make it sound as if I’m super organized, but this was the first time I’m doing this kind of work. So, it turned out I was actually quite inefficient in marshaling my sources. I learned a lot of things that I could do better in case I ever do another book based on archival research. I definitely learned that I should be footnoting and endnoting on the go, rather than leaving it all until the end, which was a rookie mistake that I think historians do not make, but journalists are certainly prone to.

What else would you do differently were you to write a book based on archival research again?

I think definitely keeping track of all my sources. So initially, when I started going through his letters, I would be very conscientious, like I would read each letter that I had, and if it was important, I would write a summary of it in my own document and tag it with some keywords. So, for example, if it had to do with his scientific research, I would tag it with research. And so, I was conscientious initially, but I think that system slipped by the wayside the further into the process I got. I think one thing I would definitely do is continue that level of conscientiousness throughout the process.

The other thing also would generally be to organize my reading better; maybe I didn’t do that well enough. These are some things, but maybe no one is ever satisfied with the way they’ve done something and there are always things to do better next time.

Your writing in this book has a very distinctive literary or narrative sense to it. Did you consciously plan on writing this story in such a way?

“I think the goal of objectivity itself is a misplaced one. I don’t think human beings are objective. We are all subjective people, and so I think it’s a little impossible even to pursue that. I think what is more important is to be fair and even-handed.”

The plan was always to write in a narrative sense, which meant including a lot of scenes and so on. That’s the only way that I know how to write. Whether in my journalism or my books, that is always my objective: to provide a narrative that is as immersive as if it were a novel, or as if it were fiction. The dialogues that you read in the book are all drawn from letters, or books, or manuscripts, or transcripts of conversations that were recorded by MI5 when they were tapping phones or listening in on conversations.

I love using dialogue in my writing. I think it really brightens up the text in a way that is otherwise very difficult to do and it also pushes a piece of writing further towards this immersive end of the spectrum. If you have dialogue between two characters in your text, it makes it seem all the more as if the reader is right there in the room with them. It’s really a very powerful mechanism in writing nonfiction, I feel, and so I was quite delighted.

You worked on this book for around four years. What was it like being in someone’s head for such a long time and witnessing their life at close proximity? Did you develop empathy for Haldane? And if so, how did you make sure you were objective while writing about him?

Yeah, it’s a weird precept of biography that you have to really empathize and be fond of the person who you’re writing about. I don’t think that’s true. Because obviously, it is, for example, impossible for a biographer of Hitler or Stalin to have empathy with somebody like that. But it’s definitely true that you end up in most cases, and definitely in Haldane’s case, with an appreciation for the complexities of an individual. He was a flawed human being in several [ways]; he made mistakes; he might not have been a nice man to know personally. But I think, at the end, when you have spent four years with the person, living in his head, it’s impossible not to come away with some kind of appreciation for what a unique individual he was.

To answer your second question, I think the goal of objectivity itself is a misplaced one. I don’t think human beings are objective. We are all subjective people, and so I think it’s a little impossible even to pursue that. I think what is more important is to be fair and even-handed. There are many people who succumb to writing hagiographies, especially when you write biographies of people who are living, who have given you access, and a lot of people yield to that temptation quite easily. In this case, there was no such pressure because he is dead, he had no children, and there are very few people around today who remember him in a personal way. So I could make my own mind up about him from the things he had written and the things that were written about him.

And because, in my mind, the linchpin of this book is this Lysenko episode, which is actually a great mistake that he made. So right away, off the bat, I’m starting with an episode that caused a lot of people to despair about Haldane. And so in that sense itself, I think I’m trying to bat away the temptation to do a hagiography—by exploring his life, essentially through this mistake. Once I decided to do that, I think it freed me up in a particular way to be open about his flaws and his faults, and it also made me feel that I could be honest when I was actually praising him as well.

Pratik Pawar is a science journalist based in Bangalore, India. His stories have appeared in Science News, The Washington Post, The Wire, Discover, and other outlets. He is a recipient of the 2020 EurekAlert! Fellowship for International Science Reporters. Follow him on Twitter @pratikmpawar.