Walls keep people out. Or drugs, or ideas. At least that’s what some people claim. A physical barrier that divides a land often comes with the promise to resolve complex problems such as immigration, drug trafficking, and terrorism. But in practice, walls rarely do so. Emerging research does suggest, however, that border walls significantly affect the people that live near them, particularly those people’s mental health.

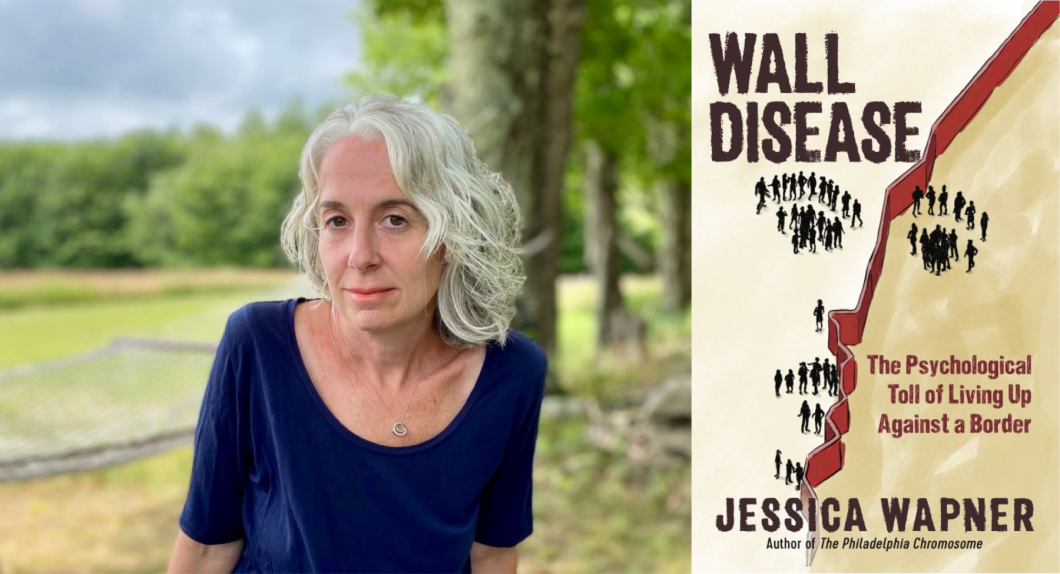

In her short book Wall Disease: The Psychological Toll of Living Up Against a Border, published in October 2020, science journalist Jessica Wapner explores how living by a border changes people. First described while the Berlin Wall was still up, the phenomenon known as Mauerkrankheit, or “wall disease,” is associated with elevated rates of depression and feelings of isolation and despair; in the most severe cases, Wapner writes, researchers have found that living near the Berlin Wall triggered alcoholism, psychosis, schizophrenia, and suicide. The fall of the Berlin Wall did not signal the end of an era of border walls. In the decade after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, she writes, “47 new border walls arose around the world…. Today there are more than 70 significant security barriers at borders worldwide.”

While the manifestations of wall disease are rarely as acute nowadays as they were at the Berlin Wall, this condition is pervasive in the often impoverished and politically disenfranchised communities being cut off by the ever-growing number of walls. From the stories of people who lived in the shadow of the Berlin Wall during the 1970s and ’80s, to the present-day U.S.-Mexico border, to the border of India and Pakistan, and elsewhere, Wapner takes readers on a global tour of the controversial walls that burden the people around them.

Wapner uses a wide lens to walk readers through the broad range of scientific efforts to study how walls alter human minds, including people’s emotional health and their social beliefs and attitudes. She talked to neuroscientists to understand how mental maps are represented in the brain and how walls and other physical barriers reshape those maps, making specialized neurons, called border cells, to signal a wall’s presence. Geographers, psychologists, sociologists, and others also offer insights, and warnings, about how border walls mold life experience. “Borderlands people remain largely forgotten in the national and global conversation,” Wapner writes. “The price of our inattention is a silent scourge of subtle but nonetheless very real mental health issues.”

While brick and metal stay put on the ground, we carry the concept of borders and barriers in our minds wherever we go. We can’t cross borders without a passport, and for some, such restrictions also take a mental toll. “Ultimately the afflicted population extends far beyond the borderlands of the world,” Wapner writes. “Most of us are unaware of the extent to which we carry the artificial construction of national borders in our minds and how they shape the way we think about the world and our place within it.”

Wapner’s book couldn’t be more relevant now. While many countries face immigration crises, the COVID-19 pandemic has only strengthened the power of borders as several countries have closed them in an attempt to keep outsiders, and the virus, out.

Here, Wapner talks with Rodrigo Pérez Ortega about her motivation to disentangle the effects of walls on people’s brains, the process of writing a book during a pandemic, and the many shades of “wall disease” that affect the people who live near walls. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

How did you first learn about the major mental health problem relating to border walls?

One of my main interests over the years has always been the intersection between science and culture, science and socioeconomic issues. I’ve been always very fascinated by how the way that a person lives, or is sometimes forced to live, influences everything about their physical health. And by fascinated, I mean, also, wanting to bring those issues to light. That’s so often where my mind goes.

I was in a writing course, and the instructor, Jacqui Banaszynski, mentioned—kind of very casually offhand—“Oh, you know, I’ve never seen an article connecting the Berlin Wall to the U.S.-Mexico wall.” And, I just started wondering if there were mental health issues about living near a border wall. I started doing some research, first looking at the Berlin Wall, and found out there was this very specific diagnosis called “wall disease.” I couldn’t believe it. Then, I wrote that New Yorker online piece about walls changing how we think … from the Berlin Wall to today.

It’s a matter of asking the right question that triggers an insightful response and, hopefully, with some great quotes along the way.

Later, an editor that I had worked with before—on my previous book, The Philadelphia Chromosome—came to me saying, “What do you think? Do you think this could be a book? Do you think there’s more?” And I thought, “Definitely.” There was more, and I actually felt that the length of the book was perfect because I don’t think a longer book would have worked. I don’t know that there’s enough material for a longer book because this is an unrecognized issue. There’s not a lot of research that I didn’t include. And I think to expand it would have meant expanding into political issues, and I wanted to keep it really about the areas that I felt comfortable writing about. I’m happy it’s short because I think that it’s hard to read long books right now. So, the idea worked out very well.

You did a lot of the reporting and writing remotely, during the pandemic. How was your experience writing a book during lockdown? And how did you manage to pull such detail and richness out of remote interviews?

I wrote the book during the most intense months of the pandemic. It was very difficult. My children were at home. We were living in a trailer at the time in cold weather. I mean, it was fine. We were safe and healthy. We were happy. We had food on the table. But concentrating was difficult.

As for the remote interviews, it’s a matter of asking the right question that triggers an insightful response and, hopefully, with some great quotes along the way. Most people were extremely happy to speak, happy to share their knowledge, happy to send references afterwards, I think because the subject matter is one that they are passionate about and that they hadn’t been asked about in this context before. If anything, it was hard to not feel that we were somehow comrades—to preserve the journalist-source relationship—because many saw me as an advocate for anti-border-wall policies. I tried to not be overly friendly, but it’s hard when you are so appreciative of the time and material people are providing.

The amount of money I was paid for the book was such that extensive traveling wouldn’t be feasible, even without COVID happening. But I also knew that I wanted to travel somewhere. It would have been slightly ridiculous to write a book about border walls without ever visiting some stretch of wall in person, and visiting a neighborhood that sits in the shadow of the wall. Most of the reporting was by phone and remote interviewing, but I did go to Brownsville, Texas. I returned from that trip a few days before everything shut down completely.

Was there something particular about Brownsville that made you confident you would find good material there?

I really wasn’t sure where to go, but I wanted to go somewhere where I could find people who were, in fact, living right near the border. I could have gone to Tijuana—that was the other top choice—or some other areas, but in the end, Brownsville made the most sense logistically. It was a lot easier because I’m based in New York. The trip gave me the most time on the ground, the least time spent getting there.

I reached out to a few people in advance, but one of my main objectives was to talk to people whose backyards are right up against the wall, and for that I just had to go there, park my car, and knock on doors.

Once I was there, I could see how ideal it was for the book. Brownsville opened my eyes to the fact that there is no hard “border” between the U.S. and Mexico. There is a wall, of course, but culturally it feels more like a slow fade. The U.S. and Mexico blend together in Brownsville. Mexican is the cuisine of choice there, and in every restaurant I went to, it felt strange to speak English. I felt like a foreigner. People stared at me because I stood out. That sensation—that I was not quite in America and not quite in Mexico—drove home the artificial-ness of the border wall. It also drove home its impact: imposing a division that doesn’t exist culturally or naturally.

Once I was there, I could see how ideal it was for the book. Brownsville opened my eyes to the fact that there is no hard “border” between the U.S. and Mexico. There is a wall, of course, but culturally it feels more like a slow fade. The U.S. and Mexico blend together in Brownsville. Mexican is the cuisine of choice there, and in every restaurant I went to, it felt strange to speak English. I felt like a foreigner. People stared at me because I stood out. That sensation—that I was not quite in America and not quite in Mexico—drove home the artificial-ness of the border wall. It also drove home its impact: imposing a division that doesn’t exist culturally or naturally.

In the book, you talk about passports and how, even if they’re not a physical wall, they change how we think of borders and traveling to foreign countries. How is this relevant to wall disease?

It became obvious pretty quickly that understanding the impact of border walls extends to all of us. Élisabeth Vallet, a geographer who I mention several times in the book, was the first to point me toward the concept—that the wall lives in us.

I was really amazed to learn about the history of passports. A hundred years ago we didn’t have passports. You could just go and it was fine and you lived where you lived and you traveled where you traveled to and you went home.

But now, think about the fear of forgetting your passport somewhere when you travel. We keep our passports in the safe in the hotel room or keep them on our person at all times. There’s a whole mindset behind that. When I stopped to think about it, I thought it is actually really weird. We’re not born with a passport attached to our bodies. We acquire it as one of the many things that this very irrational world forces upon us. So, that becomes ingrained into our minds, that countries are separate and have borders. It’s important to recognize the extent to which our belief in borders shapes how we think about one another.

You also talk about “othering,” how people start distancing and seeing those who once were their own as alien and dangerous. How does this phenomenon arise near border walls?

The concept of “othering” came up when I was writing the original story for The New Yorker. It seemed like the right word for capturing this feeling of the foreigner on the other side. It comes up again and again with border walls because, in a way, border walls are created in order for people in power to keep control over those that they’re ruling over. If we fear what’s on the other side, then we continue to think we need that ruler’s protection—the protection of the wall.

I think it’s very much like The Village, the movie by M. Night Shyamalan. It’s very poignant because we put up walls, and then we start fearing what’s on the other side, when right before it was fine. There’s the example of the peace lines in Northern Ireland, where there was a reason to put up walls between people in order to stop the violence. I thought that the data from surveys done in Northern Ireland showed really well this fear of the person on the other side. Now, those walls still exist but people who weren’t ever really affected by that violence have this sense of, “But I don’t know who’s on the other side. I’m worried about who’s on the other side, so therefore, let’s keep the walls up.”

It’s the same with the wall in Lima, Peru, that separates rich from poor—a wall that I still have a hard time believing exists. There were some excellent videos on YouTube that described that wall and its consequences.

How did you find all these clear examples of the psychological effects of border walls? It was striking to me, for example, to learn about the man in Georgia who, because of a border fence erected in a corner of disputed territory by Russia, was suddenly left out of his own country and cut off from his family.

Thank goodness for YouTube, right?! For all the craziness and dangers of YouTube, there is a side to it that is absolutely amazing: the way that it can transport you to places in the world and people that you would never otherwise see. I had seen some news stories about that man, Dato Vanishvili. Some reporters from Vice have gone there and talked to him through the fence. And there were other stories about him as well.

[Over-reporting] turned out to be a real benefit because I kept going and kept going until I really felt I had a very strong case that there is an epidemic of mental health challenges tied to living close to a border.

How did you decide on which experts to talk to, from all these different fields?

I like over-reporting. It does make everything take a lot longer, but in this case, it turned out to be a real benefit because I kept going and kept going until I really felt I had a very strong case that there is an epidemic of mental health challenges tied to living close to a border.

I’m not a psychologist or an expert in mental health, and I was writing about a problem that is not a concrete diagnosis. So it was absolutely necessary to talk to experts in many different areas to make sure that what I was writing about was real, that it was substantiated by reliable research. This involved a lot of learning while reporting. I know very little about politics and geography and international relations, so writing this book turned out to be a huge educational opportunity.

Finding the experts to talk to was a matter of combing through the literature. For me, it was necessary to talk to people about the brain and cognitive maps, and what happens when we see a wall. It was necessary to talk to people about aesthetics and what happens psychologically when we walk by a wall—what does a big chunk of concrete do to us? Does it have an effect? I just loved the research of it. And I knew that the more fields I touched on in the book, the more interesting and engaging it would be.

It was amazing to see that each field did tie together with the next one. I just felt it needed to be a mosaic in order to understand what’s happening in the border lands and what happens in our minds, what border walls do to us. One of my sources says that the wall is “the tail of the monster.” So, you’re trying to understand what effect does the tail have on us. But it was essential to get the view of the whole monster from as many people as possible.

What is one lesson that stayed with you after that writing this book?

I gravitate toward stories that “do” something for me as a human being—that move me, that aggravate me, that elevate me—and always hope that some part of whatever story I write will do the same for the reader. If there is one sentence, even one word, placed in just the right spot, that is stirring in some way, then I feel satisfied. For me, that’s what makes the work involved in writing sustainable.

At some point, the research has to move from being “interesting” to expanding my view of the world and deepening my understanding and compassion for humanity. Then, I can bring that part of myself—that part that is like Jodie Foster in Contact when she says, “I had no idea. I had no idea”—into the story, which I think becomes part of the reader connecting with the material. It’s all still a mystery, how words work. A really great mystery.

Rodrigo Pérez Ortega is an award-winning freelance science writer. His work has appeared in Science, Nature, The New York Times, Quanta, Knowable, and other publications, both in English and Spanish. He is a former TON/BWF early-career fellow and is now editorial director of The Open Notebook en Español. He lives in Mexico City. Follow him on Twitter @rpocisv.