When I called science writer David Quammen in early March, he was in the same spot where he’d been most of this pandemic year: at home in Montana, facing his computer camera, which presents the viewer with an office that Quammen calls “a cave lined with books.” By the end of the interview, I had not only learned about his newly acquired remote-interviewing techniques, but had put them into practice—on him. If he hadn’t pushed me to ask him for a Zoom tour of his office, I wouldn’t have learned that, just outside the frame, a wild animal was lying in a glass tank.

It was a world away from Quammen’s reality when he was researching Spillover, his 2012 account of how viruses jump from animals to humans, wreaking havoc in the process. Back then, he traveled to remote villages where some of the earliest Ebola outbreaks took place. He walked through ape sanctuaries trying to understand when and how HIV first entered human bodies. He crawled through caves in China, and across a rooftop in Bangladesh, looking for virus-infected bats. He visited labs in Singapore, Australia, and the U.S, all in an effort to bring the story to life for readers.

Of the 40 years he’s worked as a science journalist, Quammen has spent the last 20 working to understand zoonotic diseases. In Spillover—as well as in two of his subsequent titles, which covered the AIDS and Ebola viruses—he delivered an ominous warning that other journalists and researchers were also making: Another big pandemic, one that would spread more easily from human to human and race quickly around the world, was coming. We didn’t know exactly when or where it would arrive, Quammen wrote, but we did have enough clues to know that it was coming. If we failed to prepare, the consequences would be horrendous.

More than a year and more than 3.3 million deaths into the pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, we can say that Quammen and the others who sounded the alarm were right.

As soon as the virus began circulating, editors began to ask Quammen to write about it. But he found himself facing a new challenge. Like people around the world, he was cooped up at home—a two-story house in Bozeman within minutes of the Bridger Mountains that he shares with his wife Betsy and four animals—in an effort to help contain the very virus he would ordinarily have traveled the world to cover.

Recently, I talked with Quammen about the challenges he faced and strategies he used to report on this story of a lifetime. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

In Spillover, you wrote extensively about how the next pandemic would unfold. You said that we didn’t know when or how, but it was coming. Did you ever give any thought to what you would do when it did?

I did not have a particular plan. I had no ambitions, really, to write about emerging diseases further. I was working on a new book that had nothing to do with [pandemics], and I was in Tasmania during the month of February last year with Tasmanian devil biologists.

I think about scenes…. How can I produce something that’s more like a wide-angle movie than a play where two people are sitting on stage talking to each other?

Before I left for Tasmania, one of the op-ed editors at The New York Times contacted me in the middle of January, and said, “Would you do an op-ed for us, about this virus in China or anything else?” And I said, “I definitely will do an op-ed about this virus in China.” [Quammen’s op-ed, suggesting in late January that the novel coronavirus could be the virus he had anticipated is here]. And then after, I wrote two features for The New Yorker. [He also wrote another two op-eds for The New York Times and a cover story for National Geographic on the evolutionary origins of viruses.] So suddenly I became one of the talking heads about [COVID-19], and my publisher said to my agent, “We want someone to write a COVID-19 book.” And my agent said, “Well, David is the right person for this because he’s already written about this stuff.” Before I knew it, there was a new contract for a new book from Simon & Schuster on this subject. It’s a kind of situation that I did not seek out. It came, and it feels more like a duty than an opportunity.

When did you realize that the early news about an emergent virus in China was actually about to become something else?

It came on January 13th. I belong to a service called ProMED-mail [an online, publicly available system that researchers and public health officials use to monitor and report infectious disease outbreaks]. There are about 80,000 members, and subscribers are mostly infectious disease scientists and public health officials. I’ve subscribed to it for 15 or 17 years. And it means that about 10 times a day, we get an email reporting something about an infectious disease, somewhere in the world. Usually I glance at these things and unless we’re in the middle of an Ebola outbreak, I delete them. There was one on New Year’s Eve about a cluster of pneumonias of unknown cause in Wuhan, China. I didn’t pay attention to that. But two weeks later, January 13th, they sent out an alert and they used the words “novel coronavirus.” They knew that it was a coronavirus that had never been seen in humans. And as soon as I saw that, I thought, “Okay, this could be the next big one.”

How has the pandemic affected your work?

Well, first of all, I have great sympathy for all those people whose lives have been disrupted so that it’s hard for them to make a living. That’s not a problem that I have, because my work is explaining viruses, and there has been a strong market for explaining viruses for the last year, unfortunately. But my work is also usually traveling to spend time in the field with scientists or at least to spend time in their offices, in their laboratories with them. And I haven’t been able to do that. I haven’t been on an airplane in a year. I haven’t been more than 50 miles from my house in a year. I haven’t been in a restaurant or an office for a year. So I’ve had to figure out other ways to do my work.

From a professional perspective, how did you adapt to these very weird times?

The challenge is how to write a book about something that 200 other people are writing books about at a time when you can’t travel to walk through jungles and climb through caves. I have a plan by which I’ve been proceeding. And I don’t want to say much about it because I don’t like to talk about books before they’re written. So I’m just spending every free hour I can contacting scientists, making arrangements, preparing, reading journal articles and doing lengthy Zoom interviews. I feel like this plan, which I’m not describing, has a good chance of producing an interesting book.

Let’s talk about things that you have published. I found that in many of your recently published pieces, you create scenes by going back in time and pulling from your memories and previous reporting. Tell me a little bit about how that decision was made.

I’ll tell you, but I’ll also show you.

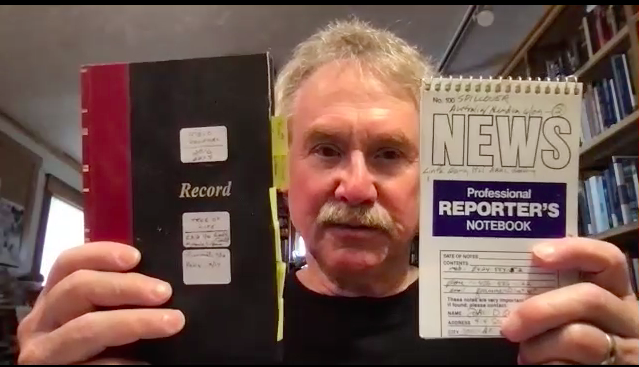

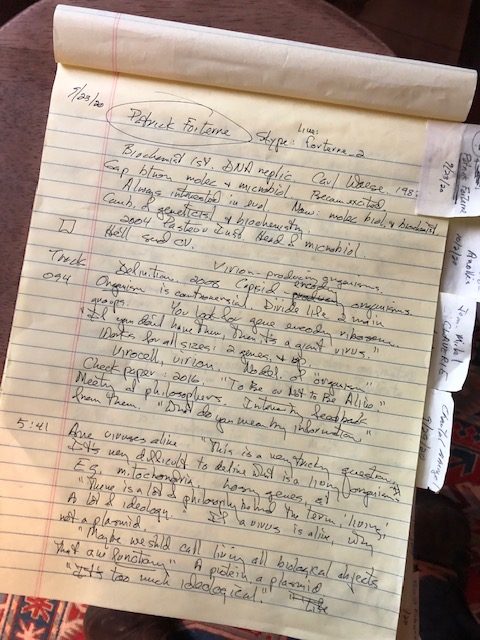

[Quammen stands up, and returns to the screen holding two notebooks. One is a black and red hardcover journal with the word “Record” printed in gold on its cover, filled with yellow Post-its between the pages. The other one is a white notebook with the words “NEWS Professional Reporter’s Notebook” printed on its cover.]

Speaking of open notebooks, here are my two primary tools. This [the white notebook] is what I use as a field notebook. And this [the black one] is what I use as a daily journal, like a diary. So when I’m in the field I’ve got these with me. I’m scribbling notes as I walk through a forest or wherever. If the scientist says something that’s interesting, I try and get it down immediately, verbatim. So what I do is I take the immediate notes with one, and then each morning I get up early and write a day’s entry that’s more narrative in the other one. And I remember things that I didn’t put in the notebook. And then I can refer back to both of these.

How many of these do you have?

I have 30 years’ worth of these things piled up in my office. And if I say to The New Yorker, “I think I should do a piece about pangolins and how pangolins might be involved as one of the hosts of the coronavirus,” then I can remember, “Oh, I saw a pangolin in central Africa in 2002.” And I can go back to this and recover the details of that scene, written when they were fresh.

I’m guessing this method of looking into old notebooks is something you wouldn’t be doing if it weren’t for COVID-19, right?

Yeah. If I’m going to pitch a magazine story, I think not just about what information I can get and who I can interview, but I think about scenes, I think about narrative. How can I do something that’s not claustrophobic? How can I produce something that’s more like a wide-angle movie than a play where two people are sitting on stage talking to each other? And for that, the only real answer right now is this [shows his field journal to the camera]. Going into the past. And not because I want to recycle material, but to find new material that I haven’t used, that’s newly relevant now. You know, I’ve only seen a pangolin one time in my life, but it was an encounter that I remembered because this poor pangolin was about to be killed for food. And it was an extraordinarily interesting, charming animal. And I put it in my journal and I never used that until last summer. And there’s a lot more in my journals that I might use in the same way until I can travel again.

Do you have a version of these two kinds of notebooks for the reporting that you have been doing during the pandemic?

No, now that I’m not traveling, I’m just sitting in this office, day after day, Zooming with people, and I’m making recordings. I’m using other systems of keeping track of things, like the Zoom recordings themselves. Like, if I were writing about you, I might say, well, “and María had a painting of a fellow with an umbrella on the wall behind her.” I don’t need to write that down now ’cause I can go back to the recording.

I remember that in one of your New Yorker pieces, “Why We Weren’t Ready for the Coronavirus,” you profile Ali S. Khan, former director of the Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response at the CDC, and you give a very vivid description of his office. Did you use this method to describe his office in such detail?

Yeah. I literally asked him to show me his office. He picked up his laptop, he walked around the room and he showed me his office and he said, “See, there’s the replica of a beheading sword from Saudi Arabia’s minister of health.” I thought, “Oh, okay, that’s pretty interesting.” Anything that would help me give some color and texture to the conversation.

How and why did you build that story the way you did?

The New Yorker called me and said, “We’d like you to do something on COVID for us.” I had an idea about the warnings that went unheard, and I remembered one particular fellow that I’d met years before at the CDC. And back then, he told me that SARS was one of the scariest disease outbreaks he had ever seen. He said, “This was a bullet that flew by our ear.” That was in 2006, I think. So 15 years ago, he said that to me, and I remember it. And then I went back to him when I was researching my book Spillover, in probably 2009, and talked to him again. I liked him, I respected him. I liked the fact that he was candid, and he talked straight. And I said to The New Yorker, what about if I make him the central figure? And they said, that sounds fine. So then I had an interview with him from 2006. I had an interview with him in 2009. I did two interviews with him by Zoom. I asked him to carry his computer around and show me the walls of his office. And that gave me some texture.

You also had these amazing resources, like the book he wrote about his life.

Yes, his father was a 14-year-old kid who walked across Pakistan to get on a boat and escape and then worked feeding a boiler here in the U.S. And when he told me that, I thought, “Oh, okay, that’s wonderful. I love that.”

How do you get a person to tell you these personal memories over Zoom?

The raw material of science stories is “like silver ore … [with] a little bit of silver in it and a whole lot of useless rock, and part of your job is to chip away and smelt that ore.”

In a sense, I’m doing what I’ve always done, which is be deeply interested in the person and the story. I think the way you get people to tell stories like that, first of all, is by wanting them to tell stories like that. And by making it clear that you care about their whole life—you don’t just want them to answer four questions. You want them. When I interview somebody, I ask questions and I get the answers, but usually what I really want is whatever story that person really wants to tell, even if it has very little to do with what I’m writing. I want to be able to awaken that person as a character in my book. [That’s why] I almost never call up a scientist and say, “I’ve got four questions. Would you answer these questions? Thank you very much. Goodbye.” That was never what I did. I was never a straight-news journalist.

Why do you think you never did that?

It’s just not what I was interested in. I was interested in telling human stories, so I generally would go there. When I was researching my most recent book, The Tangled Tree, as I got near the end of the writing, I got very interested in the work of a researcher in Paris. So I emailed him and said, “If I come from Montana to Paris, will you give me one hour to talk about your work?” I didn’t want to do that by phone. I wanted to meet him and see his office and see who he was. And he said, “Yes, I will.” So I flew to Paris and we ended up talking for seven hours. Now I wouldn’t do that anymore, because I’ve gotten used to Zoom. And because I’ve gotten more and more guilty about my carbon footprint.

The fact that you are rethinking some aspects of your reporting process is very interesting. Can you tell me about those things that you might be changing permanently, even after the pandemic is over?

Yeah, some things are changing. Now everybody is used to Zoom, and I like Zoom. I think Zoom is good. I’ve done at least 20 interviews in the last couple of weeks. And if I had to ride in a plane to go to the office of each of those people, I would have only done five interviews. So I will be more inclined to use Zoom even after the pandemic than I was before. In some ways, Zoom has advantages over a personal visit because it’s not as invasive as going to a person’s office.

And I think some people, maybe many people, have an ease in talking to somebody over Zoom that they might not have talking in person.

Are there other reporting techniques that maybe are not new to your work, but your approach is being tweaked because of the pandemic?

I read a ton of scientific journal articles. And obviously you can’t write a story just from scientific journal articles, but you can get a lot. If you are writing about science, scientists are putting down their discoveries, their methods, their ideas, and they’re doing it in a way that the average person can’t read or is never going to want to read. So it’s like silver ore: It’s got a little bit of silver in it and a whole lot of useless rock, and part of your job is to chip away and smelt that ore, and get that silver out, and then use it in your story where it will look like silver and it will not look like rock.

Do you have an example of that?

My piece [about pangolins] for The New Yorker had the title “The Sobbing Pangolin.” That image of a pangolin sobbing comes from page seven of some scientific journal paper, where the scientists said that some of these [illegally-trafficked] pangolins were confiscated by customs agents and they were still alive and kept in cages, and they seemed to be showing respiratory distress: “coughing and sobbing.” And I came to that word in the journal paper, and thought that the image of a sobbing pangolin had extraordinary emotional resonance. So from the beginning, that was the name for me. And I had found it deeply buried in a scientific journal article.

Is there anything else that I haven’t asked you about that you feel is important?

You haven’t asked me to give you a tour of my office by Zoom.

True. Can you please give me a tour of your office?

I think there’s nothing very interesting here, except a lot of books, a lot of books, a lot of books.

What’s that in the back, in the glass box? It’s an animal?

That’s my python, Boots.

Oh, wow. You have a python! How old is it?

He’s at least maybe 12 or 15 years old, and he’s four and a half feet long. He’s beautiful. We wouldn’t buy a wild animal from a pet store; he is a rescue. He was in the house of a woman who had two young boys. And they had him for a long time. And then the young boys grew up and left the house. And the woman said, “You’re leaving me here with a snake?! The snake has to go!” And my wife happened to hear. And she said, “Let’s adopt the snake.” And I said, “Let’s do.” She and I both love snakes. And so he lives in my office.

María Paula Rubiano A. is a TON early-career fellow sponsored by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and is a freelance science journalist writing about biodiversity, environmental justice, food, and sustainability for Popular Science, Audubon, Atlas Obscura, El Espectador, and more. Follow her on Twitter @Pau_Erre.