In late 2019, Ankur Paliwal, a journalist based in New Delhi, received an intriguing phone call from Mitali Mukerji, a bioengineering professor at the Indian Institute of Technology in Jodhpur. Paliwal had spoken with her as he reported other stories, and now she had a tip she thought he might be interested in.

When they met about a month later, Mukerji told Paliwal about her work on spinocerebellar ataxia, a rare hereditary disease that first shows up as a movement disorder. In some cases the condition emerges when the person is entering their teens, and in all cases it eventually gives way to debilitating loss of body control. Mukerji and other scientists in the field had been wary of drawing media attention to the disease, worried that the crippling nature of the disease and its impacts in only certain closed communities might lead to its sufferers being stigmatized. But, Mukerji had developed a rapport with Paliwal, and she said she trusted he would do justice in portraying the disease and the nuances around it.

Over his 12-year career as a journalist, Paliwal has worn several hats. He began as a trainee reporter in 2009 covering the general beat, before joining Down to Earth, an environmental magazine, as a health and energy reporter. A few year later, Paliwal went on to study science and health journalism at Columbia. Now a freelance journalist, he says he is drawn, among other things, to stories that capture “the experience of being a human and those that reveal the complexity of our lives in the places we live in.” And if issues of science are involved, he says, it’s “a perfect combination.”

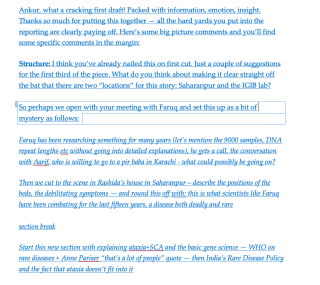

“Off Balance,” published in April 2022 in Fifty Two, is one such combination. Paliwal begins the story on the sixth floor of a genomics laboratory in Delhi, peering over the shoulder of a scientist working on ataxia, before transporting the reader to a spare home in Saharanpur, a small district in the state of Uttar Pradesh, where the reader meets the story’s central character, Mohammad Shahid, and several others in his family.

Through the course of the piece, Paliwal examines the genetics of ataxia, and explains the long history of the disease’s discovery. Readers meet a scientist who traveled the world in search of ataxia patients, and learn how the launch of the Human Genome Project spurred progress in our understanding of the genetic origin of such diseases.

Paliwal then brings the story back home, introducing a handful of researchers in India, who, despite the lack of funding and resources, have doggedly worked on ataxia. Science is an incremental process, says Paliwal, and progress is contingent on funding and researchers carrying the work forward.“ That is what I wanted to show in my piece,” he says.

The story portrays in intimate detail what it is like to live with the disease, capturing moments of personal frustration and social stigma that patients experience. Amidst the suffering, Paliwal offers a glimpse into the past lives of the patients—their aspirations and preoccupations—and captures moments of hope and joy in their lives, like one patient’s penchant for sharing inspirational Urdu poems.

Paliwal’s story is a shining example of empathetic writing—in that it spotlights nuances of the patients’ and caregivers’ experiences, as well as those of the researchers tirelessly working on the disease. Here, he tells Pratik Pawar about his reporting process and how he built trust with the patients in order to paint detailed personal portraits. He explains how he wove those together with the history of the disease and the story of how the science evolved over time. Paliwal also shares the dilemmas he faced while reporting on disability in a developing country like India, and how he made sure that he was being sensitive and fair in his reporting. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

How did you go about sourcing for this story, and how did you get people to talk to you?

So Faruq [one of the researchers] met me and I asked him if he can introduce me to some families. He spoke to a couple of patients and one of them was Rashid, Shahid’s brother in Saharanpur, and gave me his number and said that you can talk to him and see what he says. [Rashid] was very reluctant [to talk] but I said, “Can I just come and meet you?”

So I took a train to Saharanpur and met Rashid, his brothers and family, and met Shahid. I spent the day with them, just talking to them and moving around the neighborhood, where other families [with the disease] were.

In my reporting process, I generally talk to a lot of people. I met a couple of families in Saharanpur just to get a sense of who is open to what extent, while also being conscious of the fact that I am adding to their pain. I had to really navigate it very sensitively and honor their time.

For the part about whether to name or not name, or how much to reveal the identity or to what extent, that was a conversation with each family [about] what it means to have the name out, what it means if 10people from your community or outside read it. [Not explaining this] may probably work with people who have privilege and are aware, who are media savvy, but not everybody is. I think you just have to be very transparent, very honest about where you are in your research and what you’re hoping to do.

Nobody was actually comfortable with pictures. That’s why there were no pictures.

You had these different narrative elements in the story: Shahid and his family members in Saharanpur, and their experience of living with the disease; Mohammed Faruq’s and other researchers’ work on ataxia; and the long history section about the disease’s discovery. How did you decide on the narrative structure for your story?

I wanted to begin the story with Saharanpur. That was the opening scene in my draft. From there we would move through the characters to the description of the disease and from the disease we would move to the scientists.

So I sent in that outline, [and] the editors were fine with it. But when I sent the story, the editors felt that it would serve the story well if we begin with science. They said that generally stories about rare diseases begin with patients, and they wanted to give it a different treatment and make it more about science [to establish] in the very beginning that this story is as much about science as it is about people.

And how did you feel about this structural change?

I was so uncomfortable. I worried that people will think that it’s just a boring science story, and the patient’s pain or the suffering will not come across and readers will not get to that—the science [section] will be this big block that nobody will cross.

I was very concerned and had a chat with Vikram [Shah, Paliwal’s editor at Fifty Two] and he said, Let’s get a third person who has not read the story and see what that person feels, whether science is a block here or if it works. So somebody called Medha [Venkat], who does fact-checking and copyediting* at Fifty Two, read the story and she said that it works.

How did you make sure that you were being sensitive and fair to these patients while doing the reporting?

The most challenging part was meeting families, spending time with them, constantly feeling that I’m adding to their pain and feeling guilty about it, but still being selfish to get the story. So, I also thought about my reporting process. [One day] Rashida [one of the family members in the Saharanpur house] asked me point blank, Why are you doing this story? Do you want fame out of us? And that made me think a lot—like, is my reporting process extractive?

I think that was the challenging part. So it just took a lot of conversation with the families to continuously make sure that I wasn’t intruding where they didn’t want me to intrude, and [to know] how much time I could spend. I generally say, “Can I just be here for the whole day? I’ll just be a fly on the wall.” But I sensed that they were not comfortable with it. So what I did is say, “I will visit you twice in a day—I’ll come in the morning, and I’ll come in the evening. Or maybe I will come in the afternoon or in the evening for two hours. And in those two hours, I’ll be around and ask you questions.” And then I would ask them, “What did you do the whole day? What did you do in the morning?”—trying to reconstruct their day through the interviews. As journalists [or] writers, sometimes we cause discomfort to people during our reporting process, so we should try to evaluate the circumstances and comfort level of our sources in every situation and make reporting judgments accordingly.

You mentioned to me earlier that you struggled with writing about these patients with disability, specifically in the Indian or the developing-world context. Can you talk a little bit about the tension you felt between portraying disability as a major force in these patient’s lives while also showing them as whole beings, and how you thought through it?

One thing I wrestled with was, if you see in the Western journalism culture when you are writing about disability or people who are living with disability, there’s a lot of emphasis on not making it completely about just that. They are whole beings, a lot is going on in their lives and they’re able to manage it. All those Urdu couplets that you see in the story are part of that—that they think about these things, they joke about these things. And getting into the history of Shahid, that he liked to dress up, that he gave an audition for a movie, all those things, that was a conscious [decision].

But during reporting, I also felt that their life was quite subsumed by their disability and they were constantly talking about it. As much as I presented them as whole beings, they said that “our life is just about ataxia. That’s what we think about the whole day. The fact of my life is that I am bedridden, I’m wheelchair bound.” These are the terminologies that the Western press avoids. But these were the terminologies that people here were using, because our health systems or infrastructures do not support them to think differently. Essentially, disability is a lot about society.

So at that moment, I had to break free from that narrative, at least slightly, about writing about disability and let people speak for themselves and say, “That’s how I feel.” So that’s why you see the bed in the story. It’s a very conscious choice. It’s a choice to say that; that’s what the patients told me: “That’s what happens to us and our life is not the same as somebody who’s living with ataxia in Europe or in the U.S. It’s different.”

So I did struggle with it. It was a tension in my mind. More to say, a desire to present it as is, both the things—saying that they are whole beings and also saying that their life is consumed by [disease] now.

How did you go about translation? The interviews were in Hindi, Urdu, and Marathi, but the story appears in English. You also include those couplets in Urdu and follow them up by an English-translated version. Was it intentional, keeping in mind Fifty Two’s readership?

I was recording everything. I think there’s probably no conversation that has not happened in the presence of a recorder. But mostly, I had the recorder with me because I was conscious that I do not say anything that they have not said. Or if they have said something like “don’t write this,” I remember it. So I had that, and then I did the translation [of] Hindi to English myself. If I needed help with Urdu, I asked a bunch of friends in Aligarh; and the Marathi translations, the local teacher I was traveling with, he did.

I included the Urdu couplets and lines in the draft because I wanted to give a very close/intimate sense of Shahid’s family and their world. The Urdu couplets and lines were so much around me in that [patient’s] house that I couldn’t not include them in the story. And when I was writing the story, I mostly had Indian readers in mind, and I thought that they would connect with the sweetness in Urdu.

You mentioned earlier that you got the tip for this story in late 2019 and the story was published in April 2022. How did you think about financing this story on such a long time scale as a freelancer?

Honestly, it’s not sustainable. You can’t do it unless you have family wealth, a partner who works, or a side job. So I have been able to do long pieces because I have some kind of a side gig going, which pays my bills. And I cannot do any of these stories without a grant. So I would tell my editor, “I’m applying for a grant and if that comes through, I’ll do the story.” So for two years, I didn’t report this story. For one, the pandemic was happening. And second, I didn’t have the grant.

How did you approach writing this story, and did you have any models for this kind of writing in your mind while working on this piece?

There was no one piece that informed the structure and writing. There were different stories and not all of them were about diseases, but just informed the choices in the story. Like there’s this piece by Atul Gawande in The New Yorker called “Letting Go.” That was at the back of my mind in terms of explaining how families live and make decisions when there is no cure.

Then there is this piece in Runner’s World called “Twelve Minutes and a Life.” In that piece, the writer does a fabulous job in bringing the character [Ahmaud Arbery] to life in terms of what he liked, what he was all about, and that this whole thing is not just about him being shot dead. So that’s what I tried to do with Shahid’s story a little bit. So yes, there were different pieces that informed different parts of it.

Although we sometimes get inspired by the writing in established media houses abroad about the narrative and stuff, I think at some point you need to break free, because it’s the culture that informs writing and writing choices a lot of the time. The place you are in, the people you are around, [have] some sort of a worldview and you should always see your people, your place, through that worldview and not from the worldview that people in the West have. Which is why I gave that example about writing about disability—the culture is very different.

There’s that famous quote by Toni Morrison about [the] white gaze—that you should reject it. You should see your people from your gaze. They are your people, it’s your world, you have grown up with them. So always have that as you tell your stories.

* Correction 7/5/22: An earlier version of this story stated that Medha Venkat does copywriting at Fifty Two. In fact, she does copyediting there.

Pratik Pawar is an independent science journalist who writes about global health, ecology, and science policy. A TON early-career fellow supported by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, he lives in Bangalore, India. Pratik’s work has appeared in Discover, Science News, The Wire, and Undark, among other publications. Follow him on Twitter @pratikmpawar.