Cryptocurrencies have dominated the news cycle for the past several years, and for good reason. Sixteen percent of Americans have used this form of digital currency at some point, according to the Pew Research Center. And the market’s spectacular volatility—from the boom-and-bust cycles of Bitcoin to the collapse of crypto exchange FTX in late 2022—has ignited get-rich-quick dreams for some while sparking financial panic in others. But the noise pollution caused by the computers that process and churn out cryptocurrencies, and its detrimental effects on health and the environment, often remain hidden. When Popular Mechanics commissioned science reporter Wudan Yan to expose these harsh realities of crypto production, she had to search for sources far outside the usual world of tech—in the once-quiet rural Appalachian town of Murphy, North Carolina.

In her January story, “The Unrelenting Roar of a Crypto Mine Tore This Town Apart,” Yan describes how a cluster of crypto computers housed in Murphy uses a staggering amount of energy—enough to power 13,500 homes annually. The fans needed to cool this computing “mine” emit a constant roar that disrupts daily life in Murphy and drives animals away. The endless drone disturbs the residents’ sleep, causing anxiety and depression—and, for one woman, it triggers pre-existing PTSD. In other affected communities, local laws give residents legal recourse, including the option to sue crypto companies over permitting or zoning violations. But Murphy has no such laws—leaving its residents with limited means to fight back.

Yan’s story on this community’s plight and political discord deftly weaves together chilling scenes—such as when a bullet was left on the doorstep of a woman* who spoke out against the mine—with coverage of research findings showing just how much harm noise pollution can pose to human health and the environment. A freelance journalist based in Seattle, Yan spoke with Darren Incorvaia about why she decided to center her story in Murphy, how she planned out her field reporting, and how she captured key narrative moments during interviews. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

You’ve written a number of stories at the intersection of economics, public health, and the environment—such as a disgraced e-cigarette company’s attempt to revamp its image and the possible resurgence of uranium mining in the Navajo Nation. How did you come to this particular story about the harms of generating cryptocurrency?

[Features director] Matt Allyn at Popular Mechanics asked me if I’d be interested in writing a story about the noise impacts of crypto mining. At first I was hesitant, and then I looked into it a bit more and saw how much this community is being impacted. When I think about my reporting, what I’ve done, people suffering is a [draw] for me—for better or worse. For me, science writing isn’t just about the research, it’s about the people and the communities that get impacted.

How do you connect the story of communities to the story of science in your work?

As an example, early in my career I did a series [supported by the Pulitzer Center] about palm oil and whether or not it’s sustainable. I wrote about a research team that was developing a molecular tool that can help farmers determine whether or not the palm oil seed that they’ve planted is going to be productive. We have to feed the world, but we can’t feed the world by clearing more land for palm oil production because that’s bad for the environment. So the science is great in theory, but my question is, what does it look like in practice? There are the people who would be affected by the results of the science—and the greater industry at large, which scientists cannot control. Inherently, people are doing science in a place, and people and places have stories and histories that I don’t believe should be ignored.

How did the community of Murphy become the focal point of the story?

During my early research I came across a [Washington Post story about] crypto mining in Limestone, Tennessee, which is in the Tennessee River Valley just like Murphy. This story, like many others I found, focused on how miserable the residents are because of the noise. But I was wondering if there was anything more. The story quoted an outside source from Murphy, so I tracked them down using LinkedIn, and we started texting and calling. There are so many other towns where people are complaining about noise from crypto mining, so I asked them what they think makes Murphy stand apart. And they said Limestone has legal recourse, but in Murphy there are no zoning laws. They said, “If you really want to see people suffering, come to Murphy.”

You’re based in Seattle. How did you report on a community on the other side of the country?

I’ve done a lot of international reporting in the past, and I am very averse to parachute journalism, where a journalist goes to a place for a short period of time and doesn’t have much knowledge [of] or connection to the community. I think there’s a more ethical way to report on a community you’re not familiar with, and it takes time. For this story, I did a few pre-interviews, so I knew people wanted to talk to me. Then I made a six-day reporting trip to Murphy.

Popular Mechanics does not pay for travel. I negotiated a lump sum fee for writing the story, and they put some money on top of it to help cover travel. My expenses were my own, so I tried to keep costs reasonable.

How did you plan out your field reporting in Murphy?

I draw up an outline before I begin field reporting. I try to envision what the piece would look like if somebody else—a better writer than me—wrote it. What would the story need for me to feel educated as a reader? I knew I needed an attention-grabbing lede that showcases the stakes—that was the bullet on the doorstep.

I [also] needed to zoom out and put Murphy in a greater context, so I needed to explain how crypto came to be and why crypto mining happens in the U.S. Stepping outside of my brain for a moment and envisioning where I would expect to see these things if somebody else had already written the story—that’s how I come up with my structure.

From there, I figure out what parts I already have and what I still have to get in my field reporting or other reporting from expert interviews. It doesn’t make sense for me to interview seven people who can talk about the environmental impacts of noise and another seven about the health impacts. After my trip I filled the outline in.

What did you focus on in your interviews with Murphy residents?

I interview everyone as if I’m going to make a lede out of them. You might think that this is ridiculous: It creates so much more work. But it actually forces people to tell you a story. As a magazine journalist, my story has to start with a moment. And throughout the story, I have to intersperse it with other moments to keep things moving. I see [these] moments in narrative reporting as inflection points, when something changed in a character’s thinking or when they really got fed up.

For example, I remember being on the front stoop of Mike and Jennifer Lugiewicz, who lived two doors down from the mine. And Mike was just telling me about the fact that he and Jennifer were going to move, and I thought, “Oh, let’s dig into that moment.” The Lugiewiczes bought the house. They really liked it. They invested a lot in it. They had been suffering for quite a while from the noise from the mine. Then there was a moment that was like, “We have to get out of here.” What made things go from bad to worse? [Here, I would ask] what I would call an empathy question: “If I were in your shoes, I could see myself acting or thinking this way. What was it like for you?”

Another key narrative moment is when the Morrises found a bullet on their doorstep. How did you encourage them to open up about that incident?

It does require building up trust. Lynell Morris mentioned the bullet offhandedly during our first phone conversation. I made a note to follow up with her about it later. By the time I began asking her for more detail about that, we had met in person and were chatting for an hour and a half over lunch. So I think she was already warmed up to me by the time I broached it again.

Doing many in-depth interviews can take a mental toll. How do you stay motivated and focused, especially during long days of field reporting?

Interviews can be very energetically draining, so I always have snacks on me. If I’m in an energy slump, that’s going to impact the quality of the interview that I get. I also put a hard limit on how many interviews I do in a day. I think it makes me a lot more efficient.

Also, after years and years of over-reporting, I now trust my narrative sense a lot more. Some people will just say the same things as everyone else and not give any new information. So I will move on from an interview if it’s not giving me what I need.

How do you keep track of everything while reporting in the field?

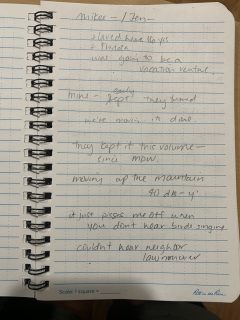

As I’m doing interviews, I am writing as much as possible in my notebooks. (I am a religious Rite in the Rain notebook user.) I’ve been field reporting since 2015, and when I’ve worked in Southeast Asia, I’ve worked with translators. And if you’ve ever had to go through the experience of listening to tape from an interview that involves a translator, you will know that it takes forever, and you will never want to do it again. So tape is a backup. I want everything I need to write the story to be in my notebook.

At the end of the day, I take a photo of every single page in my notebook and upload them to a folder in Google Drive that I’ve already organized beforehand. (When people ask me what my brain looks like, I tell them it’s a Russian nesting doll of Google Drive folders.) Then I type up all my notes into a Google Doc. This makes things searchable and makes reporting much easier. Then, after I type up my notes, I journal. I try to write about anything that really stuck out.

Did you have any reservations about how you’d be perceived as a journalist in a small, rural town like Murphy?

I’m used to taking my security seriously because of my work overseas—it’s ingrained in me. I intentionally stayed in an Airbnb that was out of the way, in case anyone wanted to track me down. Maybe this is something I think about too much as a non-white woman, but it’s not inconsequential. I’m Asian-American. In a lot of places I’ve worked, like many parts of Asia, I can blend in. But not in Murphy.

It’s a very conservative part of North Carolina, and I was cognizant of that. I think there is a narrative that people who voted for Donald Trump also think that journalism is fake. But people in Murphy were suffering. While I was nervous about how people would perceive me and my role, mostly people were really upset about what is happening in Murphy, and they wanted to talk. My takeaway from this is that no matter your politics, if you have a complaint to lodge and somebody is there willing to listen, you’ll be open to having that conversation.

What was the response to your story like, and what did you hope people would take away from it?

The response was good. There’s a page on Facebook where people who live in Murphy share news and developments, and they shared my story. Somebody in another part of the U.S. where there’s talk of building a crypto mine also wrote me a note. He said he read my story and connected the dots with what’s happening in his community.

I like to think that empowering ordinary citizens with information [that] makes them think twice ultimately leads to a better society. Suffering is something that is relatable, and can be a lens to help us understand broader systemic issues. Ultimately, I’m not canvassing and knocking on people’s doors, but I think this is the hopeful part of journalism—helping readers make better decisions.

* Correction 6/6/23: An earlier version of this story stated that a bullet was left on the doorstep of a couple who spoke out against the mine. In fact, just Lynell Morris was outspoken about the mine.

Darren Incorvaia is a journalist who writes about the natural world. He earned a PhD in ecology, evolution, and behavior from Michigan State University in 2021, with a dissertation on bumblebee behavior. He has since written freelance stories for Discover Magazine, Science News, Scientific American, and The New York Times, mostly about exciting new discoveries in the animal kingdom. Darren is a TON early-career fellow sponsored by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. Follow him on Twitter @MegaDarren.