When the moon formed 4.6 billion years ago, none of us were here to look up in wonder. But since then, the moon has shaped almost every part of our existence. The fact that Earth has seasons, that terrestrial life evolved, that humans have religion and study science—all thanks to the moon. As freelance journalist Rebecca Boyle pondered the subject of a book proposal a few years ago, she felt a draw to the moon. She had always loved writing about astronomy, and she saw a place for a book that was a full story of the moon and its role in human life. As she began to write, she realized the book had a larger mission too: It was a call to arms for people to appreciate the moon once more.

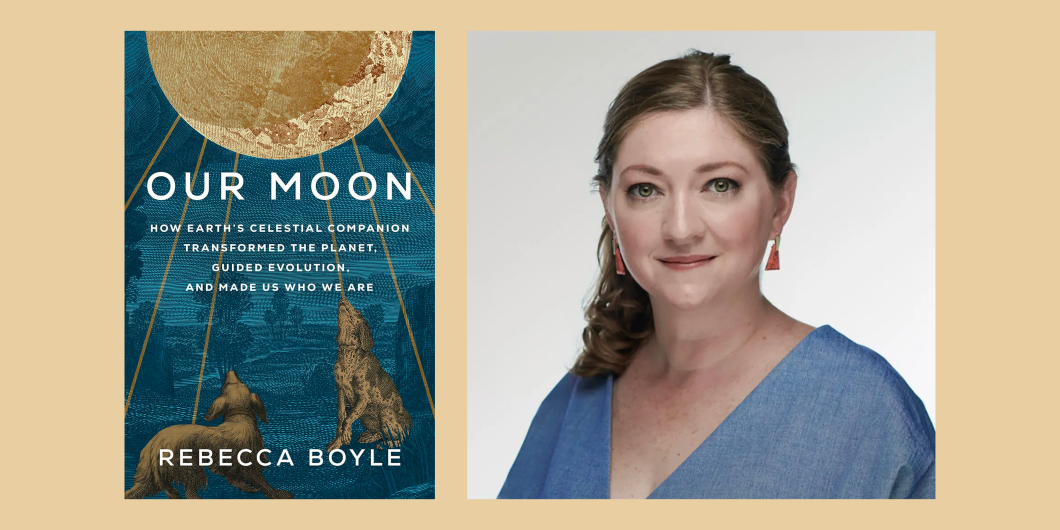

In her book Our Moon: How Earth’s Celestial Companion Transformed the Planet, Guided Evolution, and Made Us Who We Are, Boyle lays out the case for our connection to the moon. From the formation of the moon from the same cloud of cosmic dust that created Earth, to humans harnessing its powers through calendars and prophets, the moon rises central in her narrative. In the moon, she says, people see themselves reflected—both literally and figuratively—and she implores people to remember that connection as something that sustains humanity, both philosophically and scientifically. Boyle spoke with Katharine Gammon about how she crafted the book, how she turned the moon into a character, and how she found humanity in a lifeless piece of rock. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

How did you plan your travel for the book?

One thing I knew I needed to do was go overseas. I had a whole chapter about how people orient themselves in time using the moon, and I really wanted to go to two places that were representative of that relationship: Scotland [and] Germany. Scotland because I wanted to be in Aberdeenshire, where archaeologists have identified a bunch of Neolithic monuments related to the moon, including what might be the world’s oldest calendar. Germany has the Nebra sky disk—also a very early calendrical device—as well as the Ishtar Gate from Babylon.

This book is really idea-driven, but I also wanted it to be a story—I [didn’t] want it to be an encyclopedic overview of the ways the moon has affected us. I wanted to have a travel narrative, some personal narrative, and some more-creative writing. So I knew I really needed to travel and I wanted that to be done first. [Being able to report from these places in person] was so important. You can build relationships with people and can immerse yourself in their world, and get a sense for a place. Giving the sensory experience was really important to me in this book, so there was really no replacing [those trips].

My advance paid for all the travel, [and] I stacked up a lot of travel in the beginning of 2019. That was really great because when the pandemic happened, I was done with travel for the most part. Then I tried to sit and write it. I feel like I almost had to do [it] that [way] for my first book, because all the ideas needed to connect to each other. I had to have all the information I needed to be able to pull it out of my brain. If I had done it in a chunked-out way—reporting and then writing and then reporting and then writing—I don’t think it would have woven together as well. [That being said] I think if I had to do it again [in a non-pandemic situation], I would have probably broken it apart by chapters in the reporting and the writing instead of doing all the reporting [and] travel, and then all the writing.

In your book, the moon becomes a character and takes this journey across millions of years. How did you find that structure and build out the narrative arc?

This book had a couple different versions of the structure when I was drafting. The editor, Hilary Redmon, really saw from the very beginning that this is a history of thought and of ideas. We started out by having human history as the beginning of the book: Starting out in paleoanthropology, and then society and social structures, organized religion, philosophy, and then [getting to] the science of the moon’s formation. I wrote the whole book with that structure. When it was done, my editor was like, honestly, you need the moon to be the first thing. The moon is the main character of the book, the moon is the story, and so it really doesn’t make sense to have the formation come later.

We redid the whole structure, where now the book starts with the formation of the moon. It works out better: The moon is now really the main character, and then Earth has all these different things that happen to it because the moon is here.

What got left out?

Oh, man, where do I begin? I have entire chapters that I cut because I didn’t want this to be an encyclopedia—that’s not interesting. So I had to pare down. I have a whole chapter on Chinese history and astrology that I ended up cutting and incorporating into other chapters because it didn’t need to stand alone. This whole history of formation of [the] Giordano Bruno crater is cut entirely. I have a running list of stuff that’s on the cutting room floor—some of it might end up becoming feature stories.

How did you figure out what the central focus of each chapter should be?

After the first draft, my editor and I had these conversations about what the book was trying to do, what was working, and what wasn’t working as well. I was trying to leave breadcrumbs for the reader, kind of build a wave where a theme would emerge and it would kind of go away and then it would come back. It was meant to draw you along, but sometimes it would be repetitive. So I started saying: This is really about power. And this is also about power. And so all of this belongs in the chapter that really is about power. I started pulling out sections. This chapter is about time. This chapter is about religion. This chapter is about knowledge, and how people attain knowledge. A one-word billboard for each of these things really helped me synthesize what I was trying to say and be more focused—I could figure out where things had to go.

What tools did you use to organize your ideas and pull out those themes that later became the chapters?

I work in Scrivener exclusively. It’s the most powerful software because you can really use it as a way of organizing your thoughts, in a way that Word or something else just does not do. I’m a visual learner—I need to see things physically. I know a lot of writers use whiteboards or Post-it notes. Scrivener has the same capability, so it’s really convenient to be able to organize little sections at a time. I would never be able to do this without it.

What was the biggest challenge, in terms of craft?

The way that I had to approach writing. I’m a news writer: I worked for newspapers. I’ve always been an in-and-out kind of person, where I learn a lot about one thing, write my 800-word article, and move on. And this was the opposite of that. It wasn’t even a feature article. The chapters are really the support beams for the entire structure of the book. I had to totally rethink how I write to be able to do that. And it was really hard. It took a long time.

I had to learn to trust my research and be the guide for the reader, rather than being an interpreter, which is how I think of magazine writing. I had to learn that I am the expert, not just an impassive observer presenting other people’s quotes. I am the one providing the analysis of all the research and interviews I’ve done, because I am making an argument—the entire book is an argument. It really took my editor walking me through that process before I realized what I had to do.

I can’t imagine writing daily newspaper articles at this point—like, my brain would be so broken. I don’t think I’m going back to that, because [it] was so challenging to retrain myself as a writer.

Narratives really come to life with sensory details. How did you manage to include so many of them in a book about a place with no life?

I really wanted to be able to put people on the moon. I spent a lot of time watching Apollo footage and reading astronaut interviews and autobiographies about what they felt and experienced up there. There’s a lot of repetition of the overview effect, where you have this sort of new picture of humanity as one and Earth as fragile and this beautiful new vision of life in the universe as this solitary, special thing. They all talk about that.

I spent a lot of time trying to imagine it and then figuring out how to convey that. It’s so different from Earth [in] every way imaginable. Anywhere on Earth is going to feel familiar to you in some way, even if you’ve never been there before, because it’s the same planet. You can place yourself in the context of life around you. The moon doesn’t give you any of those cues. There’s no familiarity. There’s no environmental awareness that makes you feel at home, [so] I kept trying to draw that distinction. [Being on the moon] would be really jarring. I was trying to just paint that picture.

Katharine Gammon is a freelance science writer based in Santa Monica, California. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, Hakai, The Guardian, and many other publications. Find her on X @kategammon.