Writing about science for kids isn’t child’s play. And in the summer of 2023, Scienceline—the magazine run by students at New York University’s Science, Health, and Environmental Reporting Program (SHERP)—chose to dive into the challenge. Drawing on the beauty of the natural world, creativity within engineering, and scientific techniques applied to art conservation, the students created a 32-page special issue for fifth through eighth graders titled “Scienceline KIDS: When Art Meets Science.”

This issue doesn’t just educate youngsters—it also offers lessons about how to write and edit for young readers and design content to appeal to them. “Children are such an incredible audience to write for,” says Ellyn Lapointe, a recent SHERP alum who was the project editor. “It teaches you so many important skills about communicating complex ideas in a clear and effective way that are directly translatable to writing for any audience.” The issue won “Best Single-issue Student Magazine” for Region 1 in the 2023 Mark of Excellence Awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, a contest that recognizes collegiate journalism.

Lapointe led the project with Alice Sun, another SHERP alum who served as editor and art director. Both grew up reading kids’ magazines about science and the environment, and they hope the Scienceline issue inspires others the same way. Science appeals to young readers’ curiosity and can help them ask and answer questions about their world. “It’s stories that our younger selves would have also enjoyed reading,” Sun says. To help reach their target audience, Lapointe and Sun drew on previous experience as interns at Scholastic. They also arranged for an editor from Scholastic MATH to give the team a crash course on writing for kids.

The resulting magazine showcases an appealing mix of short news items, multi-page features, and visual-focused spreads. They created an online flipbook and a print version, which the SHERP team hopes to share with middle-grade classrooms in coming months.

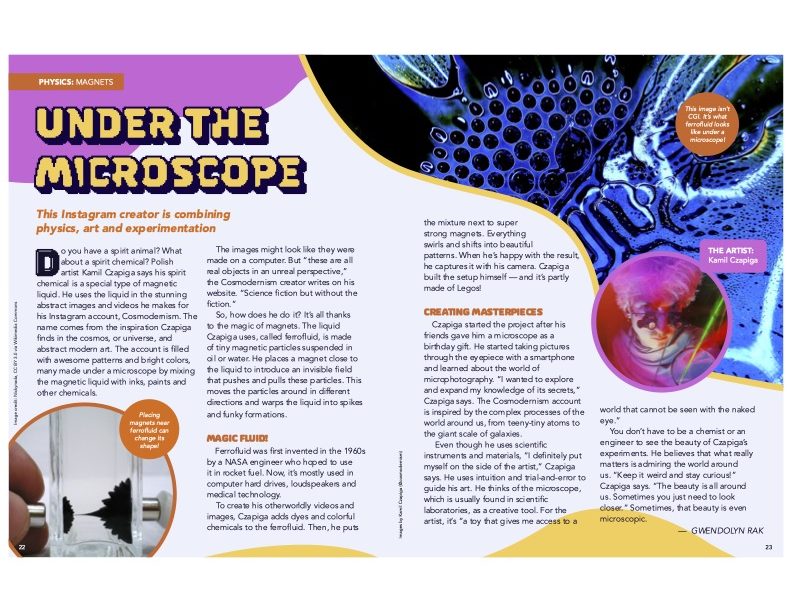

Some of the stories explore how science emerges from art, such as the materials that gave ancient works their range of hues (“The History of Your Favorite Color”) and a profile of an artist whose creative medium—a type of magnetic liquid called a ferrofluid—serves as a launchpad to explain physics concepts (“Under the Microscope”). Others highlight ways that art and science can work together to shape peoples’ experiences of both. “Tracking Temperatures with Yarn” explores artistic representations of climate change, and “Feel the Opera with Your Shirt” describes the technology behind a sensor-studded shirt that translates sounds into vibrations so deaf people can feel music.

Carolyn Wilke spoke with Ellyn Lapointe, now a science fellow at Business Insider, and Alice Sun, now an editorial fellow at Audubon, about how the magazine came together and what they learned about crafting science content for young readers. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Why did you choose middle-schoolers as your audience?

Alice: When you’re writing for really young readers, it has to be very distilled. But for middle-schoolers, the stories you can tell are more complex—more similar to writing for adults. At these grades, kids are pre-teenagers [and teens] and have a sense of how the world works. It’s a time of curiosity.

Writing for this age group was a new experience for many of your classmates. I know there are tools, such as online readability checkers, that can help writers target an appropriate reading level. How did you guide your peers through your editing?

Ellyn: Because our classmates are used to writing for adults, I anticipated that a lot of the copy would have things like extraneous detail, sentences that are really long, or buried ledes. For each story, I read through it thoroughly and pulled all that extraneous information out. I tried to find places where I could condense sentences and simplify things. I pulled out words that I thought were above their reading level and swapped them for more appropriate terms. I found more literal ways to express turns of phrase, idioms, and metaphors that don’t really land with a younger audience. When writing for adults, we try to pack several ideas into a single sentence. [Instead of] sentences separated by punctuation, like commas, semicolons, or em dashes—my personal favorite—it is really important when writing for kids to just make them separate sentences.

The big lesson that we preached throughout the entire project was that brevity is your friend. We don’t really want sentences with more than one verb or subject—just keep everything as short and to the point as we possibly can. Another big one was trying to encourage our classmates to dig into really clear and evocative, but not simplistic, metaphors. The third thing is walking a reader through a concept that’s complex, starting with the basic ideas and working your way up to more complex ideas so that the reader can really follow the flow of your thinking.

How did you approach structuring these stories?

Ellyn: Prose for adults often buries the lede. [For kids,] I usually would start with a lede that engages their curiosity in some way. I always try to stick to a really straightforward chronological telling of whatever I’m trying to convey so that they can follow the story in sequence. For adults, you want to tell your reader right off the bat what happened most recently, and then later you get into background and context. For kids, you want to make sure that, right at the top, they get the information they need to be able to interpret and digest the rest of the story.

You didn’t shy away from tackling some pretty complicated science. Can you give an example of how you approached making a complex topic accessible to younger readers?

Alice: A lot of the struggle with writing for kids is knowing what to define, what should be left out, and what we should be breaking down a little bit more. One [story where] that was particularly challenging was Gwendolyn Rak’s “Under the Microscope” [about an artist who makes videos and images using ferrofluids]. I remember having a conversation with Gwen about [how to describe] ferrofluids.

Ellyn: So if [readers] know this fluid is magnetic and they know that this artist is holding a magnet up to the fluid to create patterns, they can begin to form an understanding of what that is like. But instead of just giving the definition, you gave a little micro story about it—how it was invented, when, who made it. I think that’s a good, sneaky way to help explain a jargon term, just give a little tiny narrative about it. And then immediately they have a holistic image [of] what that thing is.

Did you use any resources to figure out how to approach complicated topics for this audience?

Alice: Knowing the Next Generation Science Standards, a set of classroom standards on what teachers should touch on [and when], was helpful. So by using the science standards, we were able to pinpoint what kids know from school in grades five through eight and match the level of information in the story to that standard. For “Under the Microscope,” we ended up being like, magnets are something they’re familiar with. So, [we could] define what a magnet is and then how ferrofluids relate to magnets.

Tell me about “Feel the Opera with Your Shirt!”

Tell me about “Feel the Opera with Your Shirt!”

Ellyn: As an engineering story, it’s one that kids don’t have a ton of foundational concepts from what they’re learning in school to support them through the story. So we kind of need to get creative and help them figure it out.

Originally, there was some complex phrasing around what is happening mechanically inside of this shirt [to translate] music into those vibrations. But for children, it wasn’t critical to them understanding the function of the shirt [worn by the story’s subject, a woman who is deaf]. We replaced it with a super simple phrase: “Her stylish blue cardigan had 16 sensors sewn into it that buzzed in time with the music.”

For kids, you want these nice, juicy sound bites. A quote that was in here originally was, “You have somebody like me, and you have to have either an ASL interpreter or captioning. But the sound shirt enhanced that experience.” For an adult audience, that quote might be totally fine. But for a kid, it was a long sentence with too many details. So the quote that we went with was totally different: “This was the first time I was really able to ‘hear’ those sounds.” Full stop. Much shorter, more emotive, and it’s not forcing kids to ask, “What is an ASL interpreter? What is captioning?”

How did you select art and images for your audience?

Alice: In terms of choosing for kids, the visual side of things is even more important. At Scholastic, we would always talk about the wow factor, especially for big spreads [focused on a] picture at the beginning. It’s hard to describe exactly what makes a good opening image, but something that is visually pleasing, makes you say wow, and piques your interest is usually a good candidate. Kiley [Price] had pitched “A Living Sculpture” [as a] longer [story], but then she showed us the photos. A woman made out of plants—it’s an image that makes you curious and want to learn more. It uses a lot of color, and having some sort of face is very grabbing.

How did you approach making visually appealing layouts?

Alice: You can use grids [that are part of design software] to break things up into columns and rows and then arrange stuff on the page. It’s a way to provide structure to organize text, images, etc. on a page in a way that’s easy for a reader to follow. And then I really just had fun with different fonts, colors, textures, and shapes. One spread I’m specifically thinking about is “Under the Microscope.” All the ferrofluid stuff is abstract shapes and these blobs and things. And I was like, what if we play with that [for shapes in the layout]? And then in terms of color, using what’s in the images to build a color palette.

What advice do you have on creating effective layouts with lots of elements?

Alice: Calli McMurray’s “The History of Your Favorite Color” had a lot of back and forth to make it easy for people to navigate. One of the things we talked a lot about at Scholastic is the reading path of a page. When you have a longer narrative piece, it’s easy to place the text. When it’s chunky, [you need] to make sure things connect as they are supposed to. And how I problem-solved it was having a central thing so that everything ties into that. [The color wheel is] the focal point and then information spreads out starting at the top corner.

The other challenge I had was for “Tracking Temperatures with Yarn.” That was originally a two-pager, but there was so much visual stuff that needed to be fit for that story. I just couldn’t get the yarn title to fit. So we [added] another two pages. That gave me a bit more space to include the title as a focal point and disperse the text and include more photos.

What are some other places where people can look for kid-centric science journalism inspiration?

Ellyn: Ranger Rick was really inspirational for me as a kid. That’s part of the reason I wanted to become an environmental journalist. And I definitely also want to shout out The New York Times for Kids—they do amazing work—NatGeo Kids, and Science News Explores. (Disclosure: Carolyn Wilke is a contributing editor at Science News Explores; story editor Jill Sakai is the managing editor at Science News Explores.)

Now that you’ve finished the magazine, what happens next?

Alice: Kiley Price has been leading [audience] engagement. We are planning to do individual spotlights on specific stories, mostly on X and Instagram.

Ellyn: Ideally, we would be going to classrooms throughout New York City with physical copies of the magazine and giving kids time to flip through them, read the stories, and ask us questions. We would have them give us feedback on the magazines. We also would like to talk a bit about what science journalism is and what we do on a day-to-day basis. As a kid who really loved to write but also had this passion for science, I think I was always afraid that I would have to pick one and leave the other behind. It’s a good time to introduce them to science journalism and get them thinking about this as a career while we’re still learning new things and really excited about it.

Carolyn Wilke is a Chicago-based freelance science journalist and a contributing editor at Science News Explores. She covers chemistry, earth science, archaeology, and animal oddities for kids and adults. Her work appears in The New York Times, National Geographic, Knowable Magazine, Undark, and other outlets. Find her on X @carolynmwilke.