In September of 2023, Karen Hao’s reporting was hitting snag after snag. Hao had traveled to Goodyear, Arizona, a town a half-hour drive from Phoenix—one of the hottest places in the country—to investigate the environmental footprint of a Microsoft data center there. But she had been stonewalled at every turn. Few people at Microsoft seemed to know how much energy and water the center demanded, and those who did weren’t willing to say. Hao managed to obtain public records on water use from the city, but they were so redacted that they provided no useful information. She’d even tried knocking on local farmers’ doors to ask them how they felt about the company’s exploits, but no one answered.

Still, Hao had a strong sense that the data center was sucking up more resources than the region could afford. Computing centers, especially those feeding power-hungry artificial intelligence operations, drain the electricity grid and guzzle a lot of water to cool their servers. Desert cities such as Goodyear barely have resources to spare in the best of times—and just months before Hao arrived, the region had experienced its worst drought in more than a millennium. In nearby Phoenix, temperatures had soared above 110°F for 55 days in 2023, a new record. Goodyear’s cheap land and relative proximity to California made it appealing to corporate investors. But placing a data center there meant putting the needs of AI before the health of the planet.

Looking for a way to capture how dire the situation was, she decided on a whim to walk around the data center in the sweltering heat. On a 97°F day, she knew such a trek would be “dangerous,” she says. But it was a visceral way to showcase just how challenging it must be to cool and run such a behemoth facility—taking the abstract problem of digital technology’s environmental toll, she says, and making it “as physical and sensorial as possible.”

Hao’s hike around the data center, which left her sunburned and dehydrated, became the vivid lede of her story, “AI Is Taking Water from the Desert,” published in March 2024 in The Atlantic. The final story did include a crucial data point that Hao dug up on the Goodyear Microsoft facility’s water use: 56 million gallons per year, enough to supply 670 families in the region, a pre-construction estimate from an obscure study. But throughout the story, Hao’s reporting shines most in the dogged approaches she took to reveal the extent of the Goodyear center’s footprint, despite the company’s evasiveness: sifting through troves of city council meeting notes, filing public-information requests via the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), pushing past terse answers during interviews, and, ultimately, leaning on the details she gathered from her personal experiences.

Shi En Kim spoke with Hao about the obstacles she faced during her reporting, and how, in spite of Microsoft’s reticence, she wove together data with narrative to showcase AI’s climate footprint. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

How did you come up with the story idea?

A researcher at UC Riverside had reached out to me with a paper that he had written looking at the water consumption of ChatGPT. At the time, I was really shocked because I didn’t realize that data centers needed water. I started looking into it and asked him also for some ideas on how to highlight this problem more, not just from a research perspective, but whether or not there were specific communities that he had come across in his research that might be impacted by this. I then got connected with someone at Microsoft, who was also quite concerned about the environmental impacts of the generative-AI push within the company. So I decided to focus on finding a Microsoft data center within a specific community that might be facing these issues. Based on that triangulation, Phoenix seemed like the most relevant place to go. Phoenix was facing all of these environmental problems and clearly had a water problem. And yet, there were data centers that were still going up.

How did you pick which data center to visit?

Microsoft, in this location, had developed three different campuses. One of them was in El Mirage, which is a neighboring city to Goodyear. It felt like I should focus on Goodyear over El Mirage because Goodyear also had two data-center campuses, so [Goodyear] had embraced them more. One of them ended up not really being an option because it wasn’t that advanced.

What was the main challenge in reporting on this Goodyear data center?

The biggest challenge was the inability to find information about the two questions that I wanted to answer: How much water is the site using? How much power is this site using? People within Microsoft don’t even really know, because that information is not fully measured or tracked internally. It’s not really shared very widely among employees. After trying an internal-sourcing strategy, I switched to government FOIAs.

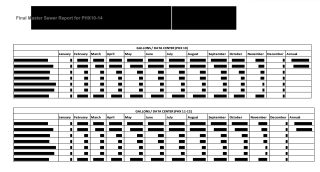

Energy is given by a private power utility company, so there’s not really any data in government databases about the energy use. But water is delivered by the city. There were actually water documents tracking how much this data-center campus was using. But when the city came back with documents about that, everything was blacked out. They said that it was proprietary to Microsoft and therefore they couldn’t provide that information.

So then I went back to Microsoft and the communications person that I had been working with through the story. I tried another tack of asking repeatedly for any information possible on these two numbers. I also did the same when they set me up with an interview with an executive at Microsoft. I just asked repeatedly in the conversation to provide anything. Every time they said no, I would reframe my question to be like, well, what about if we just looked at this piece of information?

What are some specific examples of the reframing you tried?

One question that I asked in the earlier stages was, “Can you provide me with how much power this data center uses?” They were like, “No.” Then I said, “Can you tell me what share of it is renewable energy?” Because they had made claims early when they launched the data center that it would be running on 100 percent renewable energy, and based on my understanding of how the data center had evolved, it was pretty obvious that that couldn’t be the case anymore. They also said “no” to that.

Then I said, “Is there any information that you could provide that is nonproprietary that could give readers some sense of the environmental impact of the data center?” They said “no” to that.

I also asked Noelle Walsh [Microsoft’s corporate vice president], “Does Microsoft plan to be more transparent about the environmental impacts of its investments, ever?” She said they don’t share their commercial cloud growth. She didn’t really answer the question. Then she pivoted to a question about [intellectual property].

So where did all of that leave you?

Nothing was working. At one point, I thought maybe I could sue the city, but that would have dragged the story out way longer and used way more resources. Ultimately, I just went through [notes from] city council meetings. Any reference to the data centers at all, I read all of them. I realized in a footnote that there was a document that was actually publicly available and had estimates on the amount of water that the data center was using, because Microsoft had to supply that information to the city in advance of construction to prove that they wouldn’t actually use too much water. That ended up being the number that we used.

But then, when I interviewed the city water services director, she was like, “Yeah, but it’s an estimate, so who knows?” Ultimately, I wasn’t actually able to get definitive numbers. But I did try to convey a bit of the stonewalling that I experienced as part of the story, because I think that is a really important piece—just the lack of transparency and accountability.

When did you decide to stop digging for the final numbers?

I tried asking or pushing on every possible channel that I had access to—internal sources, executive, government sources. I also contacted the power utility company and the solar panel company that they used. It became clear that unless something really dramatic happened, I just wasn’t going to get that information. At some point, I realized it’s more important to get the story out—because this is a story that’s important for people to know—rather than to get a perfect data point.

Could the story have stood on its own without the eventual water-use numbers?

It probably would have been a lot harder, because it’s then really hard to conceptualize what we’re talking about here.

We decided to do [the story either way], because my editor still felt like this was something that people didn’t really understand, and even if we didn’t have a specific number, it was valuable enough to cover it.

Did your expectations for your story change over the course of your investigation? If so, how did you deal with the uncertainty?

I rarely “anticipate” anything, because it’s too hard to know how a piece will ultimately take shape. I collect as much material as I can find during the reporting process and then sit down once I think the reporting is done, to decide how to lay it all out and whether there is in fact more reporting to do.

I knew it wouldn’t be easy to get these numbers for Goodyear, so I didn’t bank my story on getting them. Walking around the data center was just one of many things I did on that reporting trip. I also toured the giant infrastructure project that Arizona built to deliver Colorado River water to its main metropolises; I went to a town hall meeting and interviewed several people in attendance; I drove around to various neighborhoods to see what they were like; I met up with a data-center expert and a government official in person.

I once read from another magazine writer that she decides what to write about based on what sticks in her memory (without looking at her notes) after a reporting trip—because those will be the most memorable details for readers as well. So I did exactly that. When I got back, the thing I remembered most was the tour of the infrastructure project and the walk around the data center. The data-center walk was much more directly related to the points we were trying to make. When I described it to my editor, he felt it would be a great way to open up the story.

Shi En Kim is a freelance science journalist whose work has appeared in National Geographic, Scientific American, Smithsonian Magazine, Popular Science, and elsewhere. Before freelancing full-time, Kim was a life sciences reporter at Chemical & Engineering News, an early-career fellow at The Open Notebook, and a PhD student at the University of Chicago, graduating in 2022. Recently, she and three other journalist friends co-founded a science-news magazine called Sequencer. Follow Kim on X @goes_by_kim.