For a tribe that loves empirical evidence, science writers have very little data about race and ethnicity among their ranks. There’s no census tallying up the ethnicities of those who do this job. Yet when you look around the room at work, school, or professional conferences, it seems clear that people of color are underrepresented in science writing.

Why is this a problem? Apoorva Mandavilli, editorial director of SFARI.org and an adjunct faculty member at New York University’s science writing program, wrote in an essay published in Medium last year: “Without diversity in newsrooms, what you get is a small group of (mostly privileged) people writing for another small group of (mostly privileged) people. Entire stories are missed, and those that do get written have the same, tired perspectives, missing nuances of color, race, class, gender and ethnicity.”

The National Association of Science Writers (NASW) has tried to recruit more diverse journalists, but its efforts don’t seem to have worked, as Mandavilli reports.

Her story got me thinking it’s time to systematically ask science writers of color why they are underrepresented among science writers, and about their own experiences in the workplace. With The Open Notebook, I designed and distributed a survey for minority science writers. I received only 46 responses from U.S.-based respondents, itself a telling statistic: Compare that with the 618 responses to the NASW’s salary survey last year.*

The majority of respondents said they hadn’t noticed any bias against them in their careers, but a few shared stories of teachers and bosses whose actions made them feel they didn’t belong. Two people shared stories of overt discrimination.

The respondents had a lot to say about why certain racial groups are underrepresented in science writing. The most common theme was money—or lack thereof—suggesting that fellowships and scholarships intended specifically for minority science journalists may be a powerful diversifier.

The survey is of course not a representative sampling of science writers of color. The editors at The Open Notebook and I tried to publicize the survey widely—through social media, by directly contacting writers, and by posting to mailing lists, including those of the NASW, the Society of Environmental Journalists, the Association of Health Care Journalists, and several graduate programs in science writing. It’s impossible to know how those who participated in the survey might differ from the overall population of minority science writers in terms of employment status, income, geographic location, or other qualities.

Still, the individual responses and experiences are interesting, and the aggregate informative. They tell us, for example, that even if instances of bias are not universal, they are real. And identifying the causes underlying science writing’s lack of diversity is a first step toward finding solutions.

On to the results!

The Basics: Who Responded?

In all, 48 people of color responded (as did 30 white respondents, but I’m not including their responses here). Of these, two indicated that they work outside the U.S. I’ve chosen to focus on answers from the other 46, although it’s possible that some of them also work outside the U.S. and just didn’t indicate it.

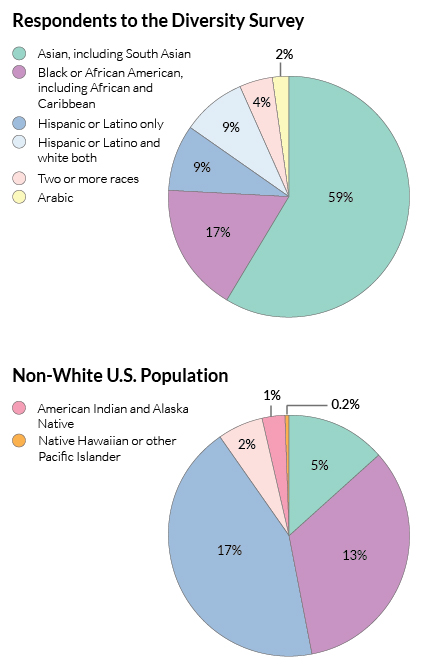

The first pie chart below reflects how respondents identified themselves according to race and ethnicity. The second pie chart shows a breakdown of the non-white population of the U.S.

The majority of respondents in the diversity survey identified themselves as Asian, including one who wrote in “South Asian.” The rest were split roughly evenly among “black or African American” (including people who wrote in “African” and “Caribbean”), “two or more races,” and “Hispanic or Latino.” The group names themselves came from my wording on the survey, which I took from the U.S. census.

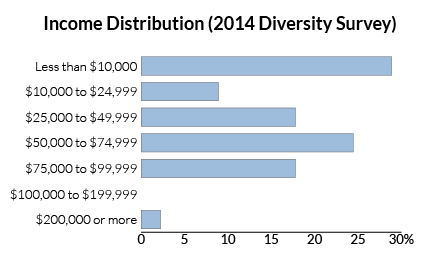

Here is a breakdown of respondents’ self-reported annual gross earnings from science writing:

(Note: Of the 13 respondents—28 percent—who said they earn less than $10,000 per year, five provided notes pertaining to their income: Two said they were students, two said they were unemployed, and one said his main income doesn’t come from science writing.)

As the chart below shows, apart from those 13, the distribution of incomes among respondents falls between the incomes of respondents to the 2013 NASW income survey who identified themselves as freelancers and those who said they were full-time staff:

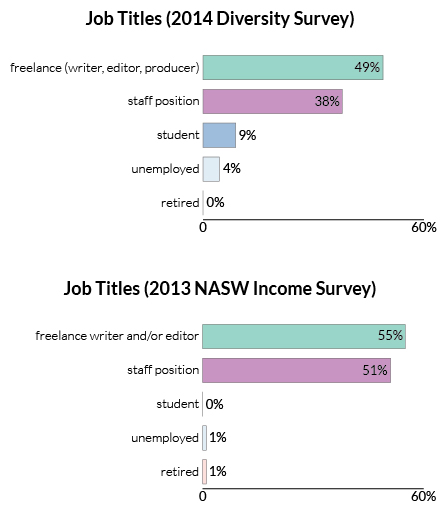

Below is a breakdown of the job titles of the survey respondents, compared to the job titles of the respondents to the NASW income survey. (Note: The NASW survey allowed respondents to choose more than one main job title—for example, respondents could check both staff and freelance boxes—which is why its percentages add up to more than 100. The diversity survey constrained respondents to choosing one main job title.)

The sample size here is small and almost certainly non-representative, so it’s difficult to say whether these earnings statistics reflect non-white science writers as a whole. They do show that the survey respondents were diverse in income.

Race and Ethnicity in Professional Life

The survey asked: Please describe some of your professional experiences as they relate to being a member of an underrepresented group in science writing.

The most common answer to this question was that the respondent had not had any such experiences. Thirteen people added statements such as “I can’t say that it has affected my job experiences much” and “I haven’t directly encountered any prejudice.”

At the same time, five told stories of subtle, seemingly unintended bias, or of incidents that made them feel they don’t belong.

One African American respondent wrote, “Access to story ideas, sources, events are not as abundant but with some networking these areas can be overcome,” while an Asian American respondent wrote, “I just think I have to work harder than others to make inroads into the network of science journalists.”

Six respondents reported occasions where they noticed being outnumbered at work, school, or professional meetings.

One respondent, who was among the first black students to enroll in a prestigious science-journalism program, described feeling uncomfortable at the “fuss” made via social media about the “historic” nature of the event. “There was this fervor that was surrounding it,” the student told me over the phone. “It felt a little bit isolating. I don’t want to ever feel like I’m obtaining the positions I want to obtain just because I’m filling some type of quota.”

The student later added in an email: “I feel that an individual should choose whether they are championed for their minority status.”

Two respondents had colleagues make untrue assumptions about them because of their ethnicity. One wrote:

“People assume I am a writer for an Indian outlet and they pitch stories they’d like to see covered in the Indian media! I am a naturalized U.S. citizen—have lived here for 18 years. It is my mile-long name, I know, but I haven’t thought of changing it.”

Another wrote, “Once during a job interview over Skype, when it came up that I was Chinese, the interviewer started talking about how he always wanted to do a story about Chinese medicine and all the weird stuff they sell in Chinatown and maybe I could do that story! I was like, ‘Yeah, sounds interesting!’ because I wanted the job, but inside I was like, ‘Seriously? Sigh.’ ”

Two respondents relayed experiences that went beyond this to more obvious bias. One woman of Mexican descent said she is fair-skinned and has found herself in groups of “Caucasians making fun of Hispanics, not realizing that I was one of them.”

An African American respondent told me in an email follow-up to the survey that when she was still a scientist, she had taken a course for scientists to learn to communicate with general audiences. The course required her to submit a piece for editing. Strapped for time, she submitted a blog post that had already been edited and published on the website of a science TV show. In other words, it was much further along than the rough drafts that the instructor had requested. “Admittedly, I cheated a bit,” she told me.

Out of drafts from “10 or 15” students, the course instructor chose her piece for public editing, alongside two jargon-filled submissions. Here’s what happened when it came time for the students to comment on the respondent’s piece:

“There was silence for a long time as folks seemingly struggled to find something to say. Finally, the silence was broken when one dude said, ‘I wouldn’t change this at all.’ Then the comments started to flow. The person who wrote the first piece said that he liked the fun word choices like: peppered, bounty, and nauseous. Then there was more silence again and the instructor urged the students [to find fault with the piece] by saying, ‘Yes. But what is wrong with this piece? I can’t quite figure out what it is.’ ”

What’s behind the Numbers?

We asked respondents: What are your thoughts about the reasons why minorities may be underrepresented in science journalism?

This question generated more responses than any other. The responses, some of them spanning half a printed page, added up to 2,558 words.

Many of the responses addressed financial concerns. Thirteen respondents said journalism’s reputation as a low-paying field may deter some minorities. Because black and Hispanic families in the U.S. have lower median incomes than Asian and white families do, would-be science journalists of color may be more likely to come from poor families, and may thus have less flexibility to take on unpaid internships, costly graduate school programs, or low-paying jobs than many young journalists do.

Even those who could take the hit may choose not to. “A history of inequality means minorities who do achieve academic success trend toward higher-paying careers,” one respondent wrote. “Science writing is an art, and as such, is devalued (read as: underpaid) in the U.S. as well as in the appreciation of minorities trying to climb the class ladder.”

Many Asian respondents cited cultural and family expectations that they would enter more prestigious or higher-paying professions such as medicine, law, or science. Similarly, two black respondents and one Hispanic respondent I talked with on the phone also said their parents wished they were doctors, especially because each had obtained some scientific training.

Five respondents pointed out that African Americans, Hispanic Americans, and some subgroups of Asian Americans are all underrepresented in science. Because many people come to science writing from careers in science, this underrepresentation may affect diversity in science writing too.

Five respondents wrote that they think many members of minority groups aren’t aware of science journalism as a profession, and five noted a lack of minority role models and mentors.

One respondent wrote that when they start out in journalism, people of color are “often shuffled into specific niches,” such as reporting on race, or may choose other specialties. Another respondent said, “If we assume that they are better represented in journalism as a whole, then maybe minorities are drawn to politics and socioeconomic issues rather than science—things that more directly affect minority communities such as politics, immigration, etc.”

Finally, two respondents noted that science writing may not allow would-be science journalists who are not U.S. citizens, but want to work in the U.S., to meet minimum income requirements for visas.

How Often Does Race Get in the Way?

We asked respondents: Have you ever felt that your minority status has affected the opportunities available to you in science journalism? If yes, how so?

About half of the survey respondents (26) said they didn’t think their race or ethnicity affected their opportunities in science journalism. But 13 said their minority status has influenced their opportunities, in both good and bad ways.

Three respondents wrote that they applied for fellowships and training programs aimed at minority science writers.

A Hispanic respondent wrote about struggling early in her career because she lacked guidance and role models. But she said she later found she was able to write stories others couldn’t. “I can interview sources in Spanish, which has certainly opened doors, and my background as both a minority and a person who grew up in a poor community has sensitized me to many of the issues I cover in unique ways,” she wrote.

The negative stories were diverse. Here are some highlights:

A respondent who is both Hispanic and white described a different effect of her minority status: “In my early career, my maiden Latina name opened doors in STEM institutions that were looking to tick those gilded boxes of ‘female’ and ‘Latina.’ It has given me extreme impostor syndrome that I cannot shake, even 20 years on.”

One Asian American respondent wrote: “The first moment of meeting a new contact or potential employer still feels like a test where I have to prove that I am just like them, and I do have things in common with them, that they don’t have to feel threatened by my ‘other’ness.”

Another Asian American respondent wrote: “I was hired by a woman who had a great experience with an Asian hire and I think that was partly why she hired me. When I left . . . I was replaced by another Asian.”

What’s Next?

Over the past year or so, science writers have launched a number of initiatives aimed at encouraging minorities in the field. The upcoming ScienceWriters2014 meeting will host diversity mixers and panels. Since last year, the National Science & Technology News Service has aimed to place science stories in African American media, and African American scientists in science stories. CultureDish.org, which launched earlier this year, aggregates events and fellowships for minority science writers.

As far as we know, this is the first survey of minority science writers. The NASW, for example, does not collect gender or race data from its members, although executive director Tinsley Davis says the association is considering adding these questions to the annual membership renewal survey. A compensation survey the association’s Freelance Committee conducted last year, which drew more than 600 replies, included a question on gender, but not one on race or ethnicity.

I hope this survey convinces science writers’ organizations that it would be worthwhile to collect more data on the racial and ethnic makeup of their members and the professional experiences of science writers of color. I thought the respondents to this survey had interesting answers to offer, and brought up important questions for future surveyors.

* Updated September 25, 2014: In the story, we made the point that the diversity survey garnered only 46 responses, while a NASW salary survey conducted last year received 618. Tinsley Davis, NASW’s executive director, emailed us to point out that the two surveys may have had different reach in part because of their distribution methods. The NASW salary survey’s outreach attempted to contact all NASW members, many of whom aren’t signed up for the listserv we emailed. We may have had better luck had we worked with NASW to reach all members; we regret we didn’t think to do so this time. Still, it is difficult to know which survey’s distribution was wider. Ours also included other science writers’ groups, which may have included people who are not in NASW. Our thanks to Davis for her email.

Francie Diep is a freelance science journalist and contributing writer for Popular Science online. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, the New York Times, and elsewhere. Follow her on Twitter @franciediep.