Science writers often endure bad weather, arduous field conditions, uncooperative subjects, and other hardships to report stories. And we do it with glee. Most of us love every minute of following scientists into the field, where we get to feel part of their remarkable jobs for a while—especially that moment when we return home and brag about it to friends and fellow writers. Why else is a grueling National Geographic assignment, for many, the pinnacle of science writing?

So when author William deBuys says reporting on endangered species conservation while hiking through a leech-infested jungle surrounded by armed men and woozy with food poisoning was a “dream come true,” we don’t doubt his sincerity.

For his eighth and most recent book, The Last Unicorn: A Search for One of Earth’s Rarest Creatures, published in 2015, deBuys, a Pulitzer Prize Finalist, joined conservation scientist William Robichaud on a three-week expedition in the remote terrain of Laos. DeBuys’s lyrical book explores what motivates Robichaud, and conservation scientists like him, to keep fighting for the survival of the nearly extinct deer-like saola in the face of the pervasive illegal wildlife trade and seemingly hopeless odds.

Traveling deep into the breathtaking Nakai-Nam Theun Protected Area, deBuys endured limited food supplies, rugged trails, armed men, unpredictable villagers, and illness. Oh, the luck! How can we too suffer for our writing? From the comfort of his adobe home office in rural New Mexico, deBuys tells Christina Selby the story behind this epic story, and how he brought the beauty and lament of conservation science to the page. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

What was it like traveling through the forest with armed men during the expedition? How did you feel about that necessity?

In the first segment of the trip we had three guys with AK-47s. That “necessity” certainly impressed upon me the seriousness of the situation—the necessity of staying on my toes, staying alert. If it had come to an exchange of gun fire with Vietnamese poachers, I wasn’t completely convinced that our three militia were going to provide a whole lot of protection. But I think more than the potential to use the arms, the important thing was just that we had the arms and that anybody else that we ran into in the forest would know that we had arms. That fact would probably have deterred conflict more than any brandishing of the arms, if that makes sense to you. But, we never did encounter poachers directly, though we had some brushes close to them. We realized by the end that we were kind of dancing with them, that they were very close to us and we were moving around each other in the forest.

Most of your work has been about the southwestern United States. What drew you to write about a story in Southeast Asia?

Most of your work has been about the southwestern United States. What drew you to write about a story in Southeast Asia?

Serendipity. It all got started in 2009. An editor I worked with, who was then still managing editor at Orion, had a moonlighting business writing stories for non-profits. That led to an invitation for him to report on a project in Borneo, in central Kalimantan. He couldn’t go, he had young children. He contacted me and said, “Would you like to go to Borneo?”

Long story short, when that project was over, I was asked to make a report on it to a meeting of the Board of the non-profit that had sent us. That was back in Washington, DC. Following that meeting and presentation, I’m here in my little casita, the phone rings and a guy says, “I was at your talk and I didn’t get a chance to introduce myself but I wonder if you would you like to write about saola?” Mustering all my erudition, I said, “What?”

That’s where it started. Within six weeks I was on a plane to Vientiane to attend the first meeting of the Saola Working Group, a group of conservation biologists organized under the aegis of the IUCN [International Union for Conservation of Nature] to save the saola from extinction. That’s where I met Bill Robichaud and began a conversation with him that led eventually to joining him on an expedition a year and a half later, in early 2011.

When you went on the expedition with Robichaud, did you have a book contract?

No. After I attended the Saola Working Group meeting, I was invited by [Critical Ecosystems Partnership Fund] to apply for a small grant. I got that grant, which was $25,000, and that paid for the expenses of my trip with Robichaud, another trip to Hanoi for interviews, and a little bit of my time that I was spending in Asia. I didn’t have a book contract until about a year after the expedition.

When I came back I began writing the manuscript. I had a strong sense of how I wanted the story to go. I wrote about 70 pages or so and that became the core of the book proposal that I fashioned around it. My agent submitted it to a whole host of publishers and it eventually landed at Little, Brown.

Did you do research before you went on the trip? How did you begin reporting?

I did some. I read some novels that are set in Laos just to get deep background and feel for culture. I read some travel books, I read a little bit of history and I tried to read up on the biology of saola. But there’s a tension you encounter going into the field. Sometimes it’s best not to know too much. In a way the writer in the field is the representative of the reader. And so, new impressions are very important. A writer who knows too much is too much of an authority. Maybe that writer will have a strong readership among experts in that particular the field, but maybe not so much among ordinary readers.

When I’ve taught writing, I try to talk, and probably not very well, to my students about trying to carry into each new subject a sort of “beginner’s mind” where you absorb a lot but you don’t close down. You keep your mind open to anything and everything that happens. You are mainly paying attention to perception and are not too full of already hatched ideas that would lead you in the direction of judgment.

When you were in the field, as you were often on the move, when did you find time to write your notes and interview people?

I wrote whenever we were still. That meant every rest stop. When we were hustling down the forest trails or bushwhacking through the forest, I was always composing notes in my mind. And then as soon as we stopped for a rest or whatever, I would whip out my notebook and start scribbling down, as quickly as I could, the stuff I told myself I wanted to record. And then I would always write a lot in the evenings and early mornings, whenever there was time.

What challenges did you face reporting from the field?

I was there mainly to be a writer but I had to contribute to camp life and so forth and I had to take care of my own gear and the like. You just wedge your own scribbling time in between what you have to do.

When I was in Borneo I discovered that with ordinary pocketbooks even if it didn’t rain, just my body sweat would soak the pages, they would stick together be unreadable and the ink would run. When I went to Laos I got these wonderful things called Rite in the Rain and you can literally write on the pages underwater. I swear by those notebooks. I had five of them, 50 pages each. I filled up 500 pocket-book pages filled with scribbles in Laos. When I worked all the way through I would flip it over and write on the back side. I started writing in the first one as the plane lifted off from LAX and I finished the last page of the last one as the plane coming home lifted off from Bangkok.

I also used a pen that never smears called a Fisher Space Pen. My toys [he laughs]. It’s great because unlike most ballpoint pens you can write with them upside down. It was developed for the space program so it would write in zero gravity. On the trail, I like to write notes lying down on my back in my tent at the end of the day.

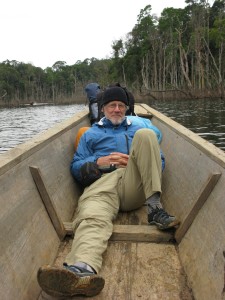

Gallery: Evolution of a Story

Images courtesy of William deBuys

Halfway through your trip the group returned to Nakai to resupply. In the book you humorously describe how after so many days of rice and small bony fish on the trail, you and Robichaud gorge yourselves on a meal in a sketchy restaurant. You ended up getting a debilitating case of food poisoning. How did you stay motivated to keep going with the trip and not stay behind in the relative comfort of the hotel when you were sick?

Oh, that was never a problem. To me it was just so exciting. For me it was like a dream come true to have an opportunity to go into a country this wild, this new, encountering the villages, the villagers and cultures I had never dreamed of encountering personally before. And then to get back there in the deep forest. I mean we were awash in beauty, it was really splendid to wake up and hear gibbons calling, the constant bird noise and chatter, the chance of seeing Doucs, the rarest monkey in the area.

You mentioned you spent quite a bit of time getting to know Robichaud before, during, and after the expedition. Did it ever become an issue for you to objectively write about him as the main character in the book?

There was a bit of a story there. I had seen pretty much from the beginning that the book had to have a central human character. People want to read and learn about other people even more than they want to read and learn about animals. I knew that the story needed to have Robichaud as a prominent character and myself as a secondary character who is the vehicle for the reader to enter the narrative. But Bill never imagined that he was going to be a character in the narrative. He thought I was just writing about saola, not about him. When he saw the first draft, he was a little bit alarmed that it focused and revealed so much about him. To his credit he got over that alarm. He understood what the book had to be.

I noticed similarities between this book and Peter Matthiessen’s The Snow Leopard. Was that intentional?

Yes, that was very intentional. I realized the situation would be best served by following the structure of The Snow Leopard, which is one of my favorite books. Once I was invited to join the expedition I realized okay, Peter Matthiessen’s done this. I know the [expedition-as-arc] structure, I know exactly how I want to approach this. In The Snow Leopard, George Schaller is the prominent character; Peter is the vehicle who carries the readers into the terrain. I knew I had to do the same thing, follow the same path with this expedition: again, a journalist or a writer and a conservation biologist, paired up in very, very remote terrain looking for very elusive, very rare creatures.

Was there anything that shifted in the editing process?

Oh yeah, a lot. The structure of the book is that the actual expedition is the line that is followed. I think of it as like a clothesline on which you hang the various digressions—the history of saola, or the background of the wildlife trade, or whatever. Those digressions were moved around and shuffled a good deal from one draft to another. Not all of them, but it took a while, sometimes, to find the right fit. I had a very good editor, John Parsley at Little, Brown, helping me with this.

In your book you explore what keeps conservation scientists like Robichaud going. It seems like the conclusion that you came to was: beauty. I thought that was really powerful.

That’s one of the things that revealed itself to me as the book was developing and became for me the most important thing I learned from the book. I think writing a book always teaches you a lot. If it doesn’t then it’s probably a stale exercise. Ideally, the writer is having a sense of discovery throughout the process and that excitement of discovery communicates itself to the reader. In the case of Unicorn, I think for me the most important set of discoveries involved the power of beauty to help us bridge the divide between optimism and fatalism. To be aware of the world, to be at all realistic, you know that things are in pretty bad shape and not trending better. And yet, you have to maintain the will and the belief to carry on and to try to make things better. Joining that realistic assessment to the hunger to carry on is a struggle for all of us—but for no one more than the conservation biologist out in the field trying to save an endangered species that is probably doomed already. The emotional and intellectual heart of the book is in that subject matter.

How do you as a writer defend beauty?

By evoking it in part. By reminding people of it, by trying to excite people about it and help people appreciate it. That’s a pretty good calling, I think. I’m a lucky person to live where I live. I look out these windows and these mountains right here are beautiful, they’re beautiful all the time. Every sunrise is beautiful. This landscape has its problems too—vulnerability to fire, and climate change, and all that stuff. But even if we chip away at the beauty that’s here, so much beauty will still remain. It’s almost a situation in which you can do the math. And the math will say that on a planet like Earth, beauty will always remain so there’s always something to protect, always something to defend.

Christina Selby is a TON fellow sponsored by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. She is a freelance writer and amateur photographer based in Santa Fe, New Mexico. She writes about conservation science, biodiversity, pollinators, and sustainable development. Her work has appeared in Lowestoft Chronicle, Green Money Journal, Mother Earth Living, and elsewhere. You can find her online at The Unfolding Earth, a blog featuring photography and environmental writing on global biodiversity hotspots; her website; or say hi on Twitter @christinaselby.