Jane Hirshfield, who has a long-standing interest in the intersection of literature and the sciences, is a former chancellor of the Academy of American Poets and the author of 15 much-honored books, including her most recent, Ledger, published today.

In this, her ninth collection of poetry, Hirshfield combines scientific precision and poetic vision to explore how human actions (and inactions) contribute to the climate crisis. The poems are infused with loss, bafflement, and possibility.

Hirshfield was the 2013 artist in residence for a neuroscience program at the University of California, San Francisco, a 2010 poet in residence for the H. J. Andrews Experimental Forest in Oregon, and was elected in 2019 to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Here she tells Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer about the personal, ecological, and political motivations for the new book.

Ledger is a tender and fearsome accounting of how humans have used and abused the planet and how, despite the beauty of the human spirit, we now face an ecological reckoning: “Ask all you wish, no twenty-fifth hour will be given.” Tell me about the process of writing it.

I’ve long written poems that speak to the crisis of the biosphere—one four-line 2004 poem, “Global Warming,” has been quoted in an environmental lawsuit brief. The crises of ice, fire, winds, drought, and flood are not newly arrived. Rachel Carson’s first book, in 1941, spoke of receding Arctic ice; the first Earth Day happened 50 years ago this spring. But the consequences of what we’ve done and do to the planet have grown ever more visible and more urgent, as has the refusal to act upon them. This book reflects that.

Ledger was written in grief and into my bewilderment at our human inaction. It was written in contemplation of the implausibility of our still standing upright, amid any sense of the normal: “If the unbearable were not weightless, we might yet buckle under the grief of what hasn’t changed yet.” The measurable evidence mounts—at worst denied, at best under-addressed—and so this is a book full of counting, measurement, numbers: the parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, the five-foot height of Captiva Island, the weight of the hand-made bones in a massive art work protesting human and animal genocide that once filled the Washington Mall. Hence the book’s title: Ledger. It reckons the sums.

Ledger was written in grief and into my bewilderment at our human inaction. It was written in contemplation of the implausibility of our still standing upright, amid any sense of the normal: “If the unbearable were not weightless, we might yet buckle under the grief of what hasn’t changed yet.” The measurable evidence mounts—at worst denied, at best under-addressed—and so this is a book full of counting, measurement, numbers: the parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, the five-foot height of Captiva Island, the weight of the hand-made bones in a massive art work protesting human and animal genocide that once filled the Washington Mall. Hence the book’s title: Ledger. It reckons the sums.

The book’s first two lines invoke human responsibility and willing denial: “Let them not say: we did not see it. / We saw.” Scientists have been trying to help us “see it” for years. How might poetry contribute to that effort?

Obliquely but insistently, I would say. There are times when simply stating the factual is enough for tears: “two billion birds have gone missing” does not need a poem. Poems, though, bring the events, knowledge, data, stories, of our lives into the orchestral, calibrating context and company of feelings. They can aerate the heart’s fields, and act as a pocketable compass. They can slip through the barricades and lead to a changed awareness of things that can neither be fully held onto nor fully forgotten.

Poems can quietly change thought’s architecture, adding windows to shift the available light and view. They can also, more simply, support. A poem tells you that whatever you feel, someone else has felt it, and lived to write it down. Equally simple: They can let scientists know their work has been seen, has been taken in by the larger public.

My last book, The Beauty, has a poem in it, “My Proteins,” that begins with the 2013 discovery of natriuretic polypeptide b, the protein that transmits the sense of itch; the poem then moves on to the microbiome. I needed these discoveries to speak of some larger things—the poem ponders the mystery of self, of its permeability to, and continuity with, what’s ordinarily thought of as “not-self.” But equally, I knew, the poem was bringing news. The protein of itch was in a freshly published paper; the microbiome’s existence and importance were not yet widely known among laypeople. And though this poem doesn’t explicitly address the crisis of the biosphere, it speaks also toward that: If we can recognize our interconnection with all other existence, perhaps we might come to better respect others’ well-being.

Science frequently informs your poems. How might poems inform science?

I once shared an onstage conversation at the Los Angeles Public Library with the astrophysicist Sean Carroll, speaking of “Ways of Knowing” from our different disciplines. The work of a poet and the work of a scientist share many things. Both are investigations, both set out to answer a question that has not been framed in exactly this way before. The questions of poetry are not frameable by any other form of thinking than that of poetry, just as the questions of science cannot be framed without the techniques, ethics, and instruments of science.

“A poem is a kind of experiment run under precise conditions, in which the reader (and the first reader, the writer) is both one of the elements and also the glass beaker in which the elements are mixed.”

These modes of understanding support one another. I draw from scientific descriptions and discoveries to know my life with an enlarged, and more precise, vocabulary. My scientist friends read poems because the discoveries of science can only take on their full meaning within full human lives. How would we recognize the magnitude of recasting our understanding of the universe as expanding if we did not have within us the capacity for awe, for surprise? Could a computer recognize any result of its computations as significant? (That’s a question I think I must now ask my friends who work in AI.) Both the arts and the sciences stand with some humility before the amazement of the given, actual existence. Both are forms of investigation that can sometimes expand the given, actual existence they respond to and question.

I’m struck by these final words from “(No Wind, No Rain)”: “What word, what act, / was it we thought did not matter?” It reminds me of the Butterfly Effect, in which even the smallest action can cause a chain reaction that results in enormous consequences. Many of the poems have already been published. Have any already had an unpredictable, larger effect?

The Butterfly Effect is exactly what I had in mind with that poem. Something minute must have altered for that large pine tree to shatter so suddenly on a windless, sunny day … but what?

I think often how much harder it is to solve a problem by the time we recognize it is a problem. How many catastrophes have never happened because of choices made long before, perhaps hundreds of years before? The catastrophes that do happen are equally the sum of many unknowable choices made perhaps hundreds of years before—to which the added weight of a sparrow, a sentence, a decision, arrives and becomes this moment’s seemingly precipitous fracture. The poem “Day Beginning with Seeing the International Space Station Above the Gulf of Mexico and All Its Invisible Fishes” speaks of this idea directly. It says of geology, evolution, terrorism, the refugee crisis in the Mediterranean: “This did not have to happen. None of this had to happen.”

For a poem with an unpredictable effect, “Let Them Not Say,” in Ledger, was written in 2014. I had at the time only the crisis of the biosphere in mind. It ended up being published and, as they say, going viral, on January 20, 2017—the day of the inauguration. That gave it a changed and broader set of meanings. It’s been much anthologized over the past three years, and has become, in its small way, something of an anthem poem for activism.

Were any poems in Ledger especially difficult to write? Or difficult to share?

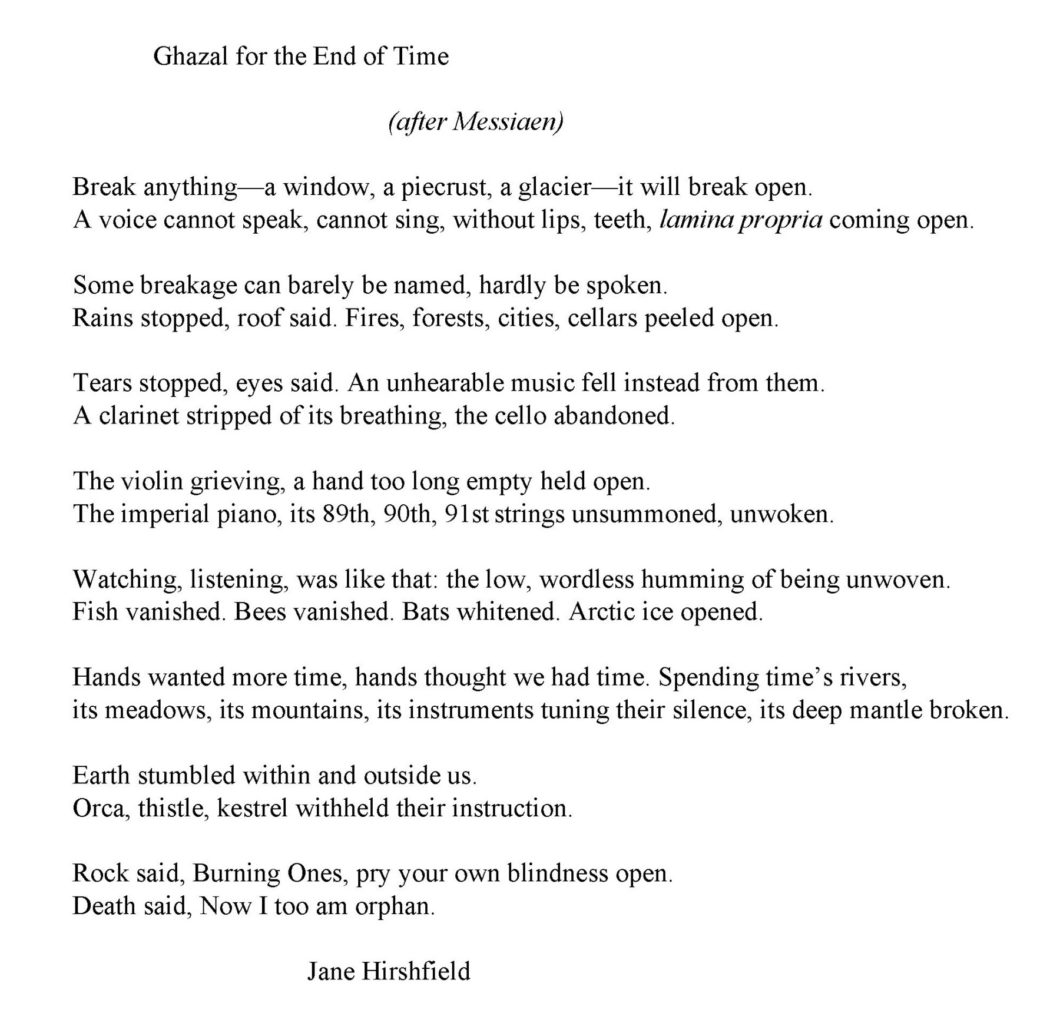

“Ghazal for the End of Time.” That poem frightens me still, it is so dark a scrying of the future.

The title is an allusion to Olivier Messiaen’s “Quartet for the End of Time,” written in a German prisoner-of-war camp. The poem uses, loosely, the ghazal form, which I first saw in the work of Ghalib, a 19th-century mystic writing in Urdu. In my poem, the sound-scheme is grounded in two near-rhyming sounds “open” and “broken.” The poem was formally difficult to write, but, much more, emotionally difficult. It looks without reprieve or consolation at our human breaking of the natural world I have so loved, so depended upon for company, calibration, and awe, all my life. When I was young, I could drink safely from any wild-running stream. Now, “Fish vanished. Bees vanished. Bats whitened. Arctic ice opened.” But it’s the last line that is so frightening to have written, so terrifying to say: “Death said, Now I too am orphan.”

I don’t in fact believe we will turn the earth into a barrens where death will not exist. Microbes, cockroaches, the opportunistic life forms (of which we are one) have great resilience. But even to imagine death as having no home, because life may no longer be here to house it … that is the darkest thought I have ever conceived.

In “Mountainal,” you write, “To be personal is easy: Wake. Slip arms and legs from sleep into name, into story.” But the invitation at the end of the poem is “to be mountainal, wateral, wrenal”—perspectives beyond the personal. Many of the poems in this book are written without an “I.” As a result, the poems themselves seem to invite a more objective way of seeing the world.

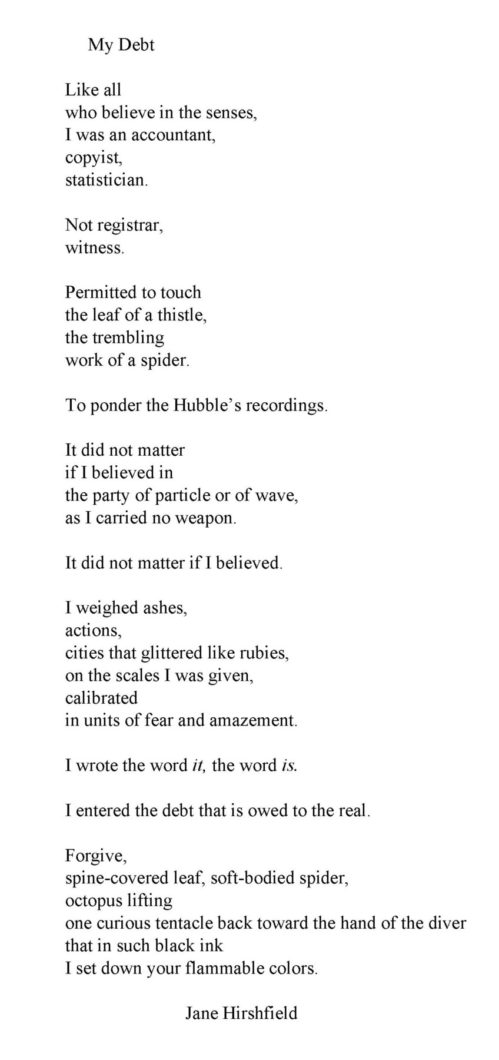

That poem led to another. I told a friend I’d written a poem I was afraid of, and she asked to see it. As soon as I sent it, I was gripped with remorse: How could I let such darkness enter her psyche? She is a person who brings immense good into this world. And in that moment of regret, I suddenly realized something else: that to despair completely is, quite simply, rude to the beauty of the living world still all around us. Awe is still possible, crickets sing in the dark, there are still pelicans, manatees, diatoms, donkeys, the Tiburon lily that grows only on one hilltop not far from my home. I then wrote what became the final poem in the book, “My Debt,” as acknowledgment and praise of all that still lives, and to offer explicit apology for the descriptions in so many of the poems that precede it: “Forgive … that in such black ink I set down your flammable colors.”

I love your perception of the effect of third-person, documenting “objectivity” in some of these poems, and also this question, for its opening of the lab notebook of writerly craft and craft’s effects. A poem is a kind of experiment run under precise conditions, in which the reader (and the first reader, the writer) is both one of the elements and also the glass beaker in which the elements are mixed. The conditions of first-person grammar are different from those of third person, as it is different to perform an experiment under the conditions of changed atmospheric pressure, changed heat or cold. It’s a complex realm, the rhetoric of grammar. A first-person poem can at times have a third-person effect, and a third-person poem can be transparently autobiographical. Wallace Stevens’s “Ariel” poems, for instance, ponder his own late-life experience, not Shakespeare’s invented being.

Similarly, the poems in Ledger written during the time of a very close friend’s dying, of glioblastoma, are about his death, but also my own death, and all our dying.

Novalis once wrote, “You spend the first half of a life looking inward, the second half looking outward.” I think this is true… not for all, but for many. The personal life continues to be the instrument through which we know any experience—we see through our own eyes and hear with our own ears. But what matters to us, over time, grows larger. I don’t think my fate is more important than that of the ants, because I’ve come to understand that my fate is not separate from the fate of the ants, or from people whose lives I may not know but nonetheless feel. And so, I began describing in 2016, on Captiva, a flying white pelican’s black-tipped wings and that turned into a poem about the destroyed Syrian city of Homs.

Interconnection-awareness supples the pronouns. One poem in the book describes this directly: “until by we we mean I, them, you, the muskrat, the tiger, the hunger.”

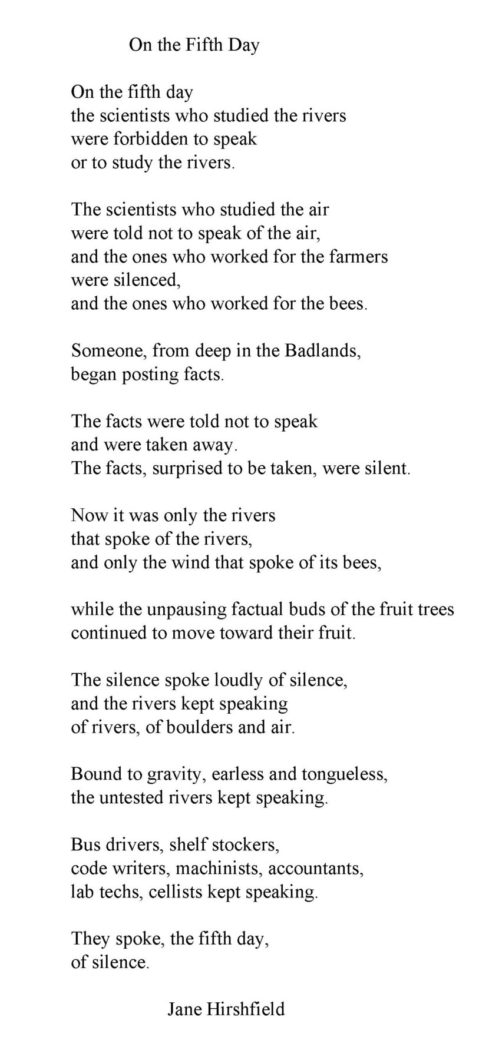

A poem late in the book, “On the Fifth Day,” was read at the March for Science in Washington, DC, in April 2017. The poem speaks of the silencing of scientists. Tell me about that event and how you became involved in it, and then in founding Poets for Science, which became the only literary presence at the March.

The earliest poems in Ledger come from the time when environmental awareness was strong but climate change awareness had not yet become foreground in the wider way it now is. Many others were written after a pivot-point: January 24, 2017, the day the news came out that the new administration had removed all references to climate change from the White House website, and instructed federal scientists not to speak publicly of their research without administrative authorization. That moment galvanized this book into the one it is.

Many of my closest friends are research scientists. This affront to their work and integrity felt personal. By the end of the evening, I had written “On the Fifth Day.” I sent it to several scientist friends. They asked permission, sent it to others, and I began receiving gratitude back from far-flung places.

The January 24th news story precipitated also the organization of the first March for Science. When I heard about it, I thought poetry should be there. A few days later I clicked on the website tab labeled “offer to volunteer,” with seven ideas for different ways to include poetry. A few weeks later I heard back from one of the organizers: They were interested in six of them. Luckily, I then found a partner: the Wick Poetry Center, at Kent State, Ohio, whose mission is bringing poetry to the public in broadly creative ways.

In the end, we put up a good-sized canvas Poetry Tent at the teach-in, in which several local DC poets interested in the sciences offered guided writing sessions. The tent’s outside and inside walls were covered with 22 human-sized banners of science poems I’d found and gotten permission to use—almost all by living poets.

Watching people’s faces change as they looked to see what this colorful set-up was about and then stopped to read the poems was a study in surprise and connection. We also made smaller placards with quotes from the poems, to be carried as signs during the march, with the march’s logo and also our own. The need for a logo is, I suppose, how “Poets for Science” was born as an entity. We offered the poems for display by other organizations and speakers at the teach-in. There was an auxiliary reading of science-related poems at the Dupont Circle Underground performance space, hosted by the DC-based activist poetry group, Split This Rock. And then I read “On the Fifth Day” from the central stand, during the pre-march rally. It had been published the previous week as a full-page section front in The Washington Post.

A poet does not imagine speaking to 40,000–50,000 people, with the Washington Monument behind her right shoulder and the White House ahead in the distance. Nor do we usually experience a poem being cheered midway through. But at the line, “and the ones who worked for the bees,” a bee contingent, up near the stage, began jumping up and down in their bee suits and shouting and waving their signs. And when I reached, “Someone, from deep in the Badlands, began posting facts,” there was a deep roar from the left-side middle distance.

The next day, a half-dozen of the human-sized banners went to New York, for display at the Universe in Verse event hosted by Pioneer Works in Brooklyn and Maria Popova of Brain Pickings. Since then, the project has traveled to a large science outreach meeting in Chicago; to the Association of Writers & Writing Programs annual conference last year in Portland; to an eco-poetry festival at the John Muir National Monument in Martinez, California; to the opening of the new Natural History Institute in Prescott, Arizona, where a few of the poems are now part of their permanent display. And just this February, the project was on display at Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, in conjunction with their Program on the Communication of Science and Technology.

The Wick hosts the project on their website and curates a Twitter feed under the hashtag #PoetsForScience. They’ve also developed a set of digital technologies for both writing and sharing science-based poems, and have a current grant in with the National Science Foundation for a new poetry and science communication project.

“The ultimate work and intention of each of these activities may seem different. But each of these three—poetry, science, and science journalism—exists to be useful to human beings in conducting our lives. And the first tool—a closely attending mind—that is the same.”

In Nine Gates: Entering the Mind of Poetry, you suggest that writing poetry requires a certain concentration, “a particular state of awareness: penetrating, unified, and focused, yet also permeable and open.” This sounds similar to the mindset of a scientist, or for that matter, of a science journalist. Is there anything you might say of the ways in which writing poems (perhaps about science), doing science, and reporting about science are similar? Or different?

I think the initial mindset must be the same. Whether doing the work of the emotions and imagination, of science, or of journalism, the first portal must be the ability to attend. There are other qualities you could add—curiosity comes to mind, for instance. But curiosity can be extrapolated from openness and permeability.

Divergences do exist. A semi-colon is not a centrifuge. An experiment is not the same as its description or a poem that later draws from it. Both science journalists and poets aim toward a discovery’s larger understanding when we write about science, but of different kinds. The journalist is (most of the time, not always) conveying the result, perhaps giving the backstory of the discovery, and connecting it to its larger consequences in ways the general reader can understand. The poet is (most of the time, not always) bringing the discovery to the page as a way toward conjuring and connecting to other realms of meaning and feeling entirely. A poem is an experiment, yet in some way the opposite of a scientific one: It leads to an irreproducible result. Even read again by the same person, a poem is stochastic and Brownian, its resonance will shimmer, change. A poem is also a kind of reporting—Gary Snyder once defined poetry as “very high quality information”—but towards different purposes than journalism (mostly) has. The ethical ground of journalism leans toward the objective. A poem’s ink is subjective. Its work is to change the inner terrain, the cognitive and emotional weather, of the person who reads it. (I hope good poems are also awake to the complexities of the ethical; interconnection-awareness and poetry’s empathic foundation require that. But I know it’s not always so. The word poetry can cover many things.)

The ultimate work and intention of each of these activities may seem different. But each of these three—poetry, science, and science journalism—exists to be useful to human beings in conducting our lives. And the first tool—a closely attending mind—that is the same.

One of the banners I made for Poets for Science holds a quote by Vladimir Nabokov, lepidopterist, poet, and novelist: “What one needs is the precision of a poet and the imagination of a scientist.” That advice about holds it, I think.

All poems © Jane Hirshfield, from Ledger, NY: Knopf, 2020; used by permission. All rights reserved.

Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer co-hosts Emerging Form, a podcast on creative process. She teaches poetry for mindfulness retreats, women’s retreats, scientists, hospice, and more. Her poetry has appeared in O Magazine, on A Prairie Home Companion, and in Rattle.com. Her most recent collection, Naked for Tea, was a finalist for the Able Muse Book Award. Her next collection, Hush, won the Halcyon Prize and debuts in 2020. Since 2006, she’s written a poem a day.