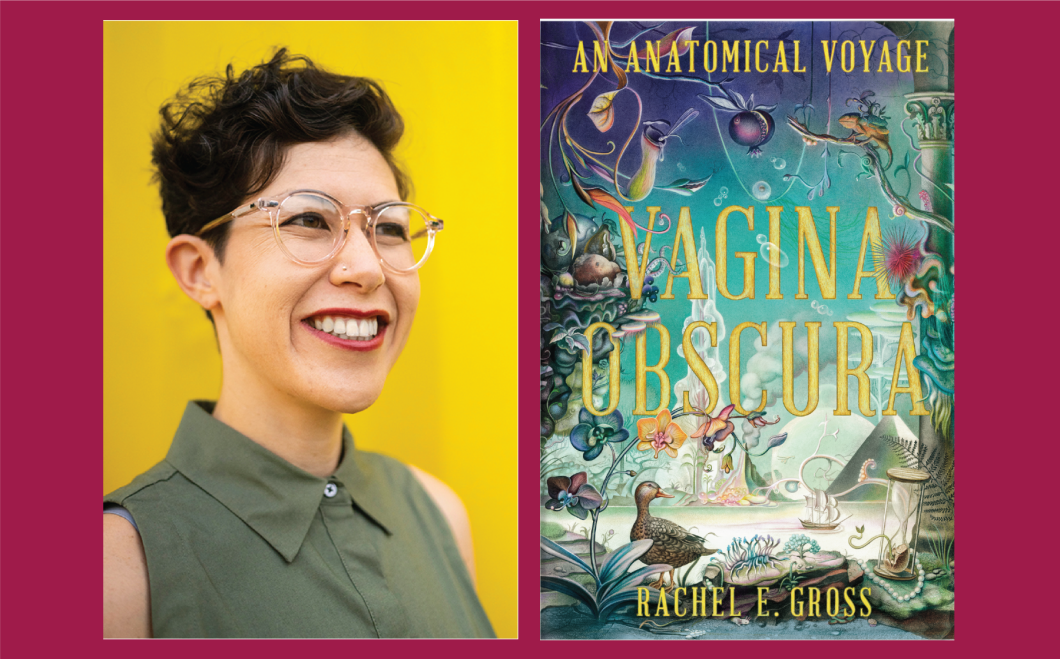

You might think that when you write a book about anatomy, you could rely on some well-established terms, but for the vagina and other organs of the pelvis, the terrain can be surprisingly unstable—and often unexplored. When I spoke with Rachel E. Gross about her book Vagina Obscura: An Anatomical Voyage, much of our chat centered on words and how we used them in our books about human genitalia and related structures.

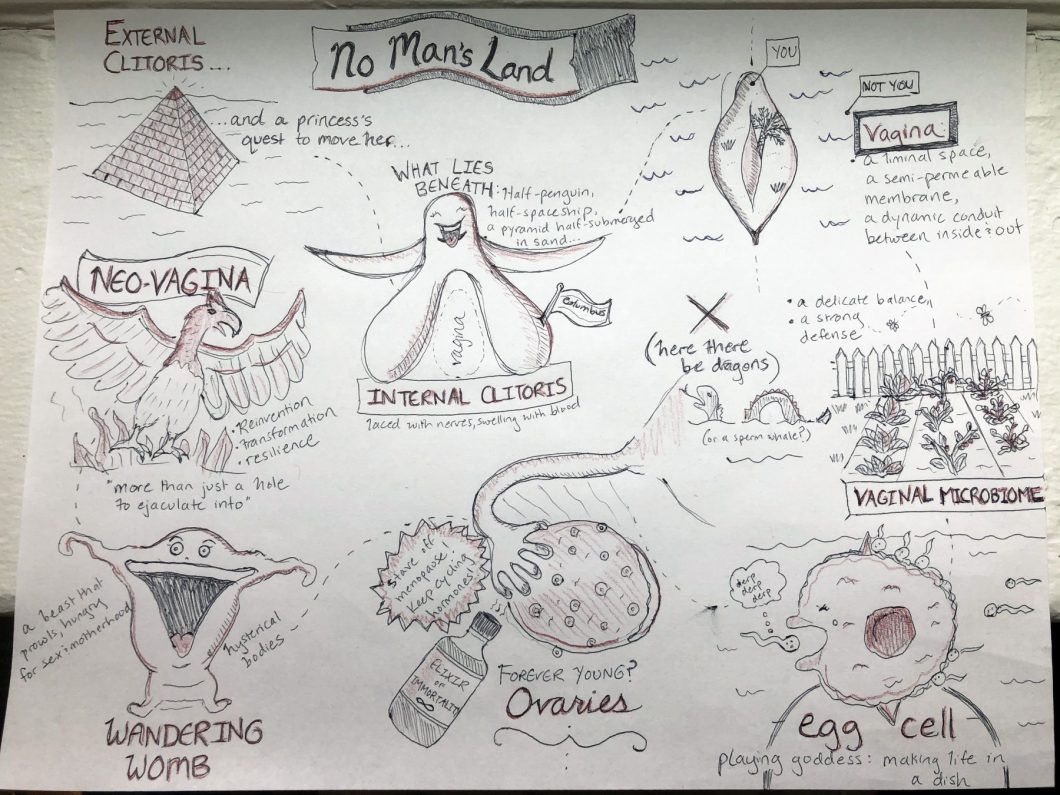

That focus is deliberate, both for this interview regarding best practices with tricky, socially sensitive material and trauma, and for Gross’s book, publishing on March 29. Vagina Obscura is the vessel for a reader’s journey through human anatomy that science and medicine have systematically overlooked, mislabeled, stigmatized, and, yes, obscured. Some navigators on this journey have themselves gotten hopelessly lost, such as Sigmund Freud, as self-deluded about the function of these body parts as Christopher Columbus was about world geography. But modern-day guides increasingly have gotten better bearings, mapping the anatomical territory of the pelvis from perspectives that, like their subject matter, also often have been excluded.

As these discoveries have emerged, some language that science and medicine apply to pelvic anatomy has been dusted off and polished to a beautiful clarity—and some has not. As I wrote for the cover of Vagina Obscura, “Gross clears away the linguistic and scientific shroud from the least investigated and most misunderstood structures in the human body and tells their story deftly and beautifully.” Even with these efforts, though, the language can still be blunt and imprecise, not quite enough to capture the true contours of what more recent explorers are discovering—and as Gross discovered, for writing a book about them.

In tracing what science and medicine have gotten wrong about these organs, Gross herself serves as a guide to the course corrections that are finally getting them right. She turned to history and historians, medical and scientific archives, and today’s scientists to uncover the obscured history of the vagina and the structures that often co-exist with it, including the ovaries, uterus, and clitoris. In doing so, Gross took her own journey, which required transcending the constraints of English and the human insistence on binaries when it comes to all things sex and gender. Every step involved in writing the book, from the title to the final line of the text, required close attention to terminology and phrasing related to sex, gender, race and ethnicity, and trauma.

For Gross, that meant turning to sensitivity readers to vet the words and using sensitivity in working with those whose difficult stories she tells. It meant working through several drafts to ensure respectful and representative language and phrasing. And it still means having to deal with the practicality that for now, the English language remains a limiting factor on finding and using terms that capture both the precision and the breadth of what the “vagina and colleagues,” as Gross sometimes calls them, represent and for whom.

Gross and I talked about the strategies she used in grappling with these issues and how she sought to ensure sensitivity in her words and actions while chronicling this journey into the vagina and its colleagues in the pelvic region. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

When the book was first conceived, it had a different title. Can you talk to me a little about the evolution of the title and what was behind that?

The working title was Lady Anatomy, and that came partially out of a column that I launched and edited at Smithsonian about women who shape science. This great writer, Leila McNeill, did a column on a female Italian anatomist in the 18th century [Anna Morandi, who reportedly even caught the interest of Catherine the Great of Russia], known sometimes as the “Lady Anatomist.” That always stuck with me; it had a ring to it. When I started looking at this book as kind of a journey to the center of the female body, I was thinking about both the anatomy of women and women who became explorers of this anatomy, and Lady Anatomy seemed to do both and became the working title.

But I ended up looking into such a large spectrum of bodies that the word lady seemed to limit the focus of the book and who might read it. I was looking at nonbinary people, trans men and women, intersex people—and the female body was more of a lens onto these unanswered questions about a multitude of bodies. About two-thirds of the way through, we realized we needed a new title.

And we just didn’t have a title for months. It was really difficult because you’re trying to do a book on “female anatomy” that doesn’t reduce people to their genitalia. So I ended up submitting like five titles, one of which was Vagina Obscura. I did like the ring to it, but I was really thinking of camera obscura and the way these early pinhole cameras do reflect the world, but they do so by either making it dimmer or inverting it, doing something that gives you this narrow specific perspective on the outside world. That’s what I came to think of these early anatomists doing with the female body. They did explore it, and they did map it, but they came with this specific lens that really limited what we saw and created a lot of gaps in our knowledge.

You open the book with a really personal story, one that I think both sets the stage for “normalizing” a story like this and probably creates some sense of, Wow, I can’t believe she disclosed something so personal! Can you talk a little about how you settled on this story as your opener, and what it feels like to anticipate that it will be out in the world and people will be reading about your vagina?

I should mention that I had BV, or bacterial vaginosis, kind of an ecosystem shift in the [microbiome of the] vagina. I tried out using this story as an opener and as a window into the themes I was going to explore about stigma, shame, and the really shocking lack of knowledge about super common vaginal issues and reproductive biology. I found out through my own research that this is a common condition that one in three American women have had at some point, but I had never heard of it, my gynecologist didn’t have many ways to treat it, and it was something I felt I couldn’t talk about in public. It was just this useful little example of what goes on with vagina research in the real world.

That experience did crystallize to me the kind of person I was writing for and the reasons we needed to lift some of this stigma. I felt this weird sense of shame and inability to communicate this vagina issue, and I am a person with very little shame, as anyone will tell you.

Lastly, I felt like I asked for so much from a lot of the researchers that became main characters in this book. I asked them to go into their personal life and their histories and their challenges. I actually ended up feeling like I owed the reader at least some small window into my experience and who the heck was I coming into this wider story.

In this book, you’re writing about anatomy that is associated firmly, in most people’s minds, with a sex binary, and that can be a vocabulary minefield. Can you talk a little about how you approached your language choices?

Female and woman were the big ones. I need to mention up front the difficulty of using [the terms] woman and female, and that not everyone who has these body parts is a woman or considers themselves female. I don’t want to fall into the trap of gender essentialism.

This kind of gets back to the working title of Lady Anatomy, that it became clear early on that I needed to be a lot more expansive about who I was talking about while still being anatomically specific. The title has “vagina” in it, but the book isn’t about the vagina, it’s about the vagina and colleagues. But the closest term that researchers use is “female reproductive system,” and there is so much wrong with that.

Even the word reproductive I came to think of as pretty loaded, especially when I was working on the clitoris chapters. “Female reproductive system” leaves out a lot of other components, namely sexuality, sexual pleasure, and sexual function, which are really minimized, dismissed, or glossed over in the case of women. If you call it the “female reproductive system,” fine, people know what organs you’re talking about, but you’re limiting your scope of inquiry in a profound way and limiting who you’re thinking of and what kind of bodies you’re thinking of.

A good portion of the book deals with the history of science, and we talk about Freud and Darwin and the Greeks and the way that they viewed “the female body.” I did make an author’s note at the beginning to say that I do use “women” as shorthand in the historical sections. I wanted to keep the reader in that history, in that historical period, and show how these scientists were thinking about people with this anatomy.

Wherever I get an opportunity, I try to remind the reader that we’re not just talking about people who would identify as women today. But it’s not perfect—there was no perfect solution to this. I’m still searching if anyone has any ideas.

Did you use sensitivity readers in preparing the book?

Yes, I did. I had three expert readers or reader groups read the early drafts. They gave me a lot of feedback, and I drastically changed my language and edited the next draft based on that feedback. I did have researchers or activists from specific communities read specific chapters. They caught things that I never would have, and they helped educate me for writing on these topics in the future.

One example was the use of the phrase enlarged clitoris, which medically was often used to describe intersex people with a clitoris larger than average. I had mimicked that language just a few times in the book. It was brought to my attention by an intersex person that some people consider that to sound pathologizing. Also, it puts the emphasis on the process of enlarging rather than on the size and brings up the question of, Who is to say that this is “too large”? We are talking about a part of the body with a huge spectrum of natural variation, and it was a pretty arbitrary decision by doctors—what counted as an enlarged clitoris. It was something that I wanted to critique and question and not just parrot.

The next two questions are about trauma. You talked to a lot of people who had undergone some really significant trauma. What did you do to get ready to talk with people who had these experiences and to talk with them in a trauma-informed way?

I’ve written about the Holocaust before, at a Jewish magazine I worked at and in other venues in which I talked to second-generation Holocaust survivors. I interviewed an oral historian at the Holocaust Museum in DC and walked through with her how to interview a survivor sensitively. But I hadn’t had a project where I talked to so many people who’d undergone this kind of medical trauma and where it might be a larger focus, so this was something that I knew I needed to be aware of and really humble about.

I came to them with a lot more transparency about the project than I might have if they were researchers or public figures. I explained to them what the chapter or section was trying to achieve and gave them an overview of the whole book. I explained why I was hoping to include their experience and offered to go over all the details that I hoped to use. I did that at the beginning so that they knew exactly what to expect and wouldn’t be surprised by anything that was published.

Doing the interviews in person or over video helped me to see cues, like a break in the voice or a silence or facial expression. I would check how they were doing, if they wanted to pause or continue or not answer that question, and if they felt comfortable before continuing. At the end of the interview, I would always explain the timeline, and we’d find a way that worked for both of us to go over the material again and make sure they were comfortable with it. And I thanked them profusely for sharing their experience.

From a practice standpoint, did you do anything differently with sources who shared such personal experiences?

For the book reporting, I was immensely concerned with doing right by people who had gone through trauma and that became trickier to work out than I had thought. In my more newspaper-style reporting, there are often strict policies about what you can show to a source, as you know—especially don’t show an unfinished manuscript. In this case, there were sections that were so personal and that I felt needed verification factually and emotionally.

I did end up sending a few passages to sources, and that did make me feel more comfortable that this would be out in the world. These were not public figures or even big researchers [but] people who had generously shared often harrowing experiences with me. I had to think through what I owed them in terms of their personal story and their experience reading the book and having it be in the world.

Race and ethnicity are playing a huge role in the history of what you’re writing about here. Did you have sensitivity readers for those parts of the book as well?

I was really cautious about how to approach the ugly racial history of gynecology, and I knew at some point that the history of J. Marion Sims would have to be central to the book. [His work] was by many historians’ accounts the founding of modern gynecology, and it is extremely significant and integral that this enterprise relied on the bodies on enslaved women.

So what I tried to do there was really rely a bit more heavily on historians and experts that had deep, deep knowledge of this history and their conclusions and make myself recede even further into the background.

In this case, I did speak extensively with historian Deirdre Cooper Owens [a professor at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, and author of Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology]. I read as much as I could about this history, I spoke with her and other historians, and tried to lift up their conclusions and do a ton of citing and attributing. In that case, I actually had her look at sections of the draft as well. I could not afford to get things wrong.

One of the sensitivity readers was a woman of color, a nurse practitioner with a PhD who’s done research on women’s health, and specifically did research on the intersection of race and BV [bacterial vaginosis]. She was supersensitive to these topics and was one of the sensitivity readers for the whole book.

People reading your book will have different responses to different aspects of it, each along a spectrum. From a practice perspective, do you have a plan for how you might respond to or incorporate comments or feedback? Do you have a strategy in place that you’ve mapped out?

I don’t know, do people have strategies? [both laugh]

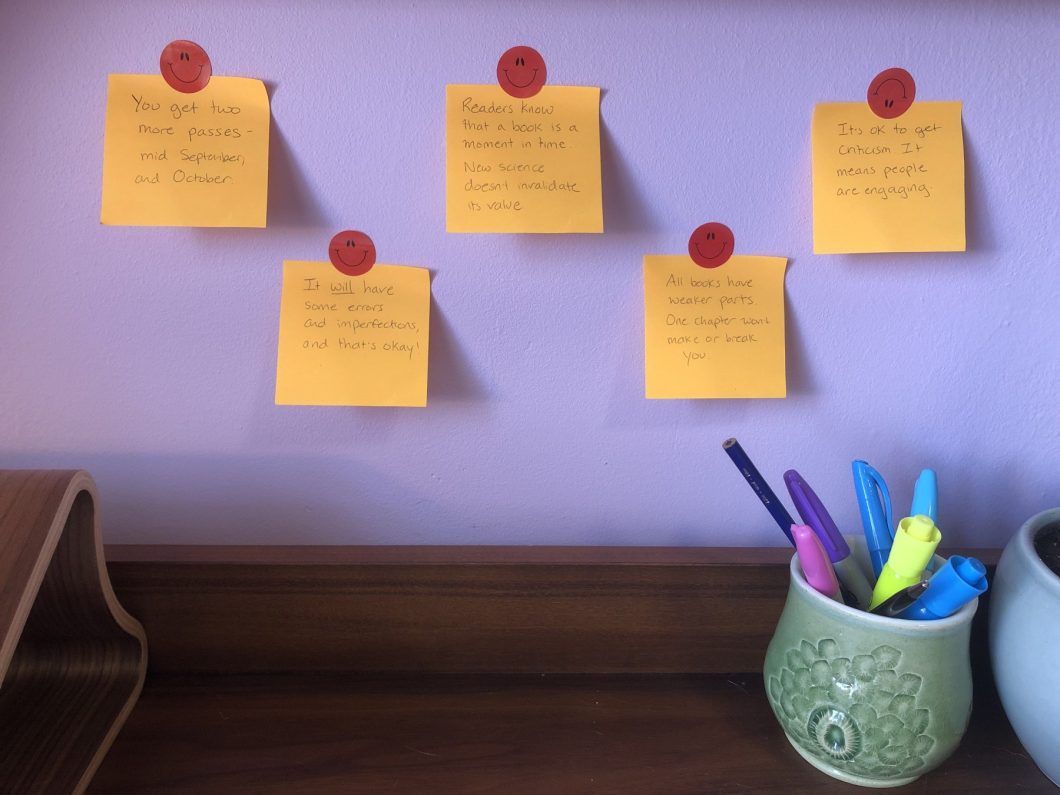

No, I don’t have a formal strategy. Yes, I anticipate many, many responses, particularly what I could have focused more on and what I could have focused less on. There are so many communities’ stories that touch on this history and are deeply intertwined. But I realized that I could only write one book, and it was not going to be the book, it was going to be a book.

I know this is not recommended, but I do read all the comments [on my articles], and they definitely feed into my story ideas. I look for gems in the comments, and that would be the same for the book. I do want to see what people were frustrated with.

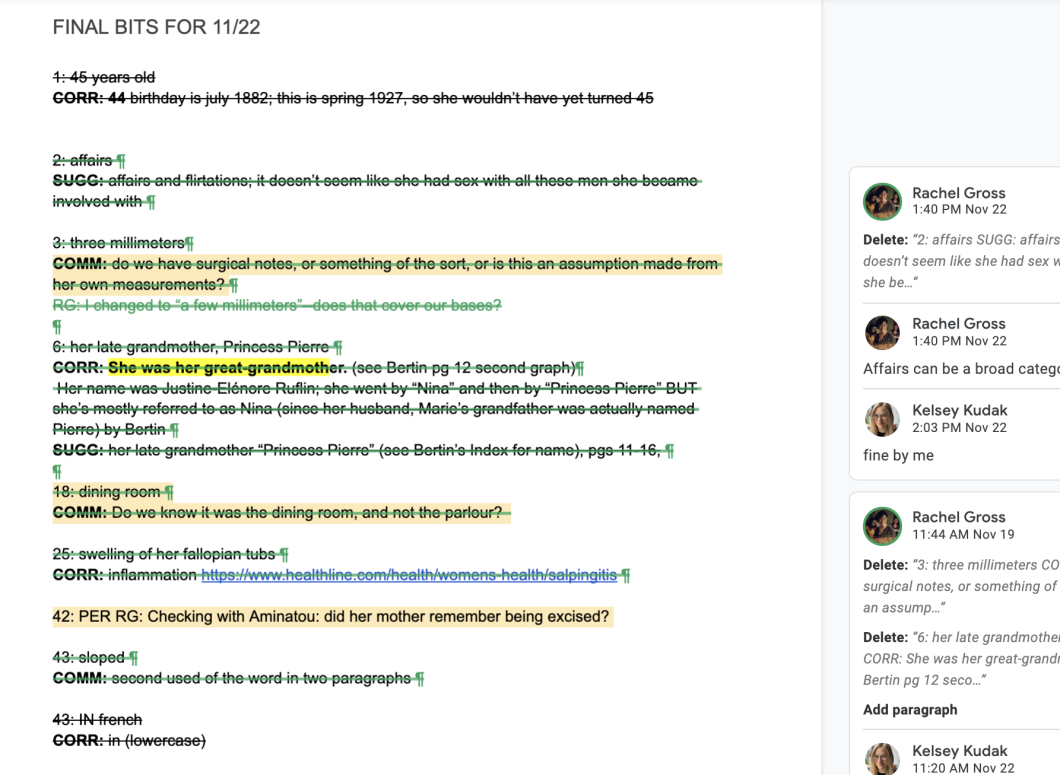

Of course, accuracy is one of my primary concerns, and I will absolutely correct factual errors. There are a lot of facts in the book and a lot of stats, and I did have a fact-checking process and a fact-checker. But I’m sure I didn’t catch everything. I don’t have a process of dealing with extremely negative hateful comments yet.

We all run into this no matter what: How do you deal with it when new things come up after publication that might change the story in some way? How do you keep such things on your radar for updates?

It’s kind of like the book research and the reporting never end. It’s just that the book is yanked out of your cold dead hands at a certain point, and so it’s frozen in that moment in time.

I do keep a list of new studies and articles that might have bearing on what I’ve written. I kind of think of it as—as long as my larger takeaways and questions and reporting are sound, changing those details is something that I can do and be transparent and let the reader know that this is an updated version.

I also anticipate learning a lot in events and book talks. I expect to be schooled in a lot of things. In the end, you do your best and hope the readers will be gentle with you, and you make it clear to them all of the practices you put into place to try and get it right.

Emily Willingham is a science writer and author of The Tailored Brain: From Ketamine to Keto, to Companionship, a User’s Guide to Feeling Better and Thinking Smarter and of Phallacy: Life Lessons from the Animal Penis. She is a regular contributor to Scientific American and a member of the National Association of Science Writers. Follow her on Twitter @ejwillingham.