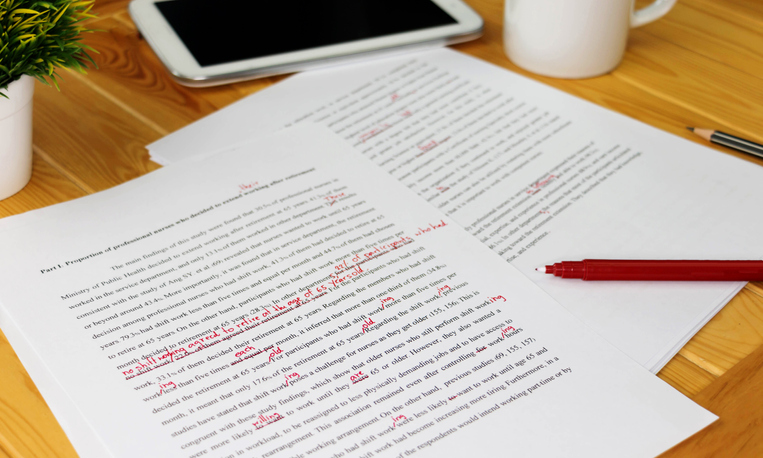

The day has come—an edit of a big story lands in your inbox. But after you open the file, your heart sinks as you scan a sea of red ink. “That’s it,” you think. “My editor hates me. This story will be killed. And I’ll never work again.” Or, instead of wallowing in despair, you’re driven into a defensive fury: “How dare they cut the most important point?” And you fire off a rage-reply. Before you know it, what might have been a simple revision has turned into an existential crisis or a knock-down-drag-out fight.

Of course, writers and editors alike would prefer to avoid both of these outcomes. To that end, I asked a group of seasoned journalists how writers can approach the editing process to make it run as smoothly as possible—while keeping their writerly voice and self-confidence intact. What follows is a frank discussion of dos and don’ts that was conducted via a shared Google document.

The conversation covers when it’s best to pick up the phone, how to handle conflicting edits, and what to do if you disagree with an editor’s changes. It also serves as a reminder that tensions, within reason, are just part of the process. But the editor-writer relationship doesn’t have to be a fraught one. “We’re all on the same team with the same goal,” says Undark editor Brooke Borel. “To get a clear, accurate, engaging story for readers.”

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity. The editors and reporters in the discussion are:

Brooke Borel, articles editor at Undark

Alan Burdick, an editor on the health and science desk at The New York Times

Zoraida Portillo, deputy editor at SciDev.Net, Latin America and the Caribbean

Brendan Maher, features editor at Nature

Meghie Rodrigues, freelance science journalist for outlets including Nature, Eos and The New York Times Magazine

Hillary Rosner, assistant director of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado

Humberto: What can writers do to make sure they understand what editors expect at the outset of working on a story?

Brooke: I know this isn’t always possible for freelancers, but it can be really helpful to jump on the phone or Zoom to talk through the story, from the reporting plan to the structure to potential reporting snags. This is particularly true for longer or more complex pieces. At Undark, we also have a guide for writers who are new to us, which outlines our expectations.

Brendan: To second Brooke’s point, getting on the phone with an editor at the outset is critical. If you find yourself starting to dig into a story and the reporting just feels aimless and unproductive, get back on the phone. Going back over the details of the assignment, refining the topline, or asking for clarity on the main question the story is looking to address is totally reasonable. For complex stories, or for writers I’ve not worked with before, I like to set a check-in time several weeks before a deadline.

Alan: Ask. And if it still isn’t clear enough (and it might not be; editors don’t necessarily know exactly what they’re asking for at the outset), ask again. And as Brooke and Brendan noted, much better to have an actual conversation on the phone or video chat; it’s too easy for nuances to get lost in an email exchange.

Humberto: Should writers be concerned about bothering editors as they work on a story? This might especially be a concern for new writers, who want to leave a good first impression.

Hillary: I do think there is a line between useful dialogue and hand-holding. It’s a great idea to have that initial chat, and it can be helpful to check in about things that come up along the way. But you also need to use your own judgment and problem-solving skills.

Zoraida: Writers must bear in mind that the editor has to attend to many tasks and writers. So, the writer should go to the editor when it is truly necessary and with specific and coherent questions. The best impression writers can give to the editor is their work.

Meghie: I think the worst type of required attention is when the reporting is flawed or when the reporter doesn’t do [their] research well enough. You don’t want to be known as a journalist who doesn’t do the homework and has to be told what to do.

Alan: It’s true—you don’t want to be known as “a writer who takes a lot of work.” You do want to be known as a writer who takes the initiative in their reporting and information-gathering, and I’d say that also applies to the work you do with your editor: keeping the lines of communication open, letting your editor know how your reporting is going, any challenges you foresee. The less guessing your editor has to do, the better—and they’ll appreciate your thoughtfulness in keeping them up to speed.

Brooke: I personally don’t mind talking through whatever is bothering a writer or coaching them through a tricky story. I’ve heard some people describe the editor role as part therapist, part coach, part barkeep, which is often true, at least for me! (Of course, we’re a lot of other things, too.)

Humberto: What should writers do if they are running behind on a deadline or encountering challenges in the reporting or writing process?

Hillary: Always be transparent! Your editor can be your best ally, but not if you leave them in the dark. I once commissioned a feature from a well-respected writer who had bylines in lots of glossy mags, and I was shocked when his deadline came and went with no word. I had my own deadline to meet, and having to track him down was maddening. It turned out he’d known for weeks he wasn’t going to make the deadline, and if he had simply told me, it would have saved me a lot of stress.

Meghie: At least with me, editors have always understood and we have found a solution. As a reporter, you can never forget that you and your editor are a team, and being transparent is key for the teamwork you’re doing.

Humberto: Should writers be fact-checking their stories as they go or wait until later in the editing process?

Hillary: Your life will be SO much easier if you make notes for yourself on where you got all the info. You can create a separate doc for yourself where you list the various facts and where you got them.

Brendan: Well, Brooke is the expert here: Buy her book! I personally like to start keeping records of where I found things pretty early in the drafting process and annotate my first draft to make assembling that info easier later.

Brooke: At the end of the edits, when the story is as near-final as possible (although, of course, you should be verifying information as you report). When you try to fact-check before it’s finished, you run the risk of going over material that will get cut or drastically altered.

Meghie: Listen to your editor about the fact-checking process and follow the steps that publication requires. But always keep your references and materials in order so that you don’t have to redo the research all over again.

Regarding [fact-checking] annotations, I don’t like working on cluttered drafts myself, so I always send copies as clean as possible, linking to reported material as hyperlinks within the text. Even if those are removed as it’s edited, going back to older draft versions and looking at hyperlinks can help a lot in the fact-checking process, especially if you have to send a separate fact-checking document.

Humberto: In your experience, what are the most common mistakes that writers make in responding to edits?

Brendan: 1. Assuming that a simple question requires a ton of extra research and revision without asking first. 2. Accepting all changes on the assumption that the editor knows what they’re doing. 3. Rejecting changes on the assumption that the editor doesn’t know what they’re doing.

Zoraida: 1. [Having] a bad attitude or [taking] a defensive stance. 2. Not answering the question and instead sending a link where to find the requested information. 3. [Sending] a lot of information so the editor [has to choose] the most suitable [fix]. 4. Delaying a response [when they’re unhappy with an edit].

Brooke: I’ve seen all of the above. I’ll add one more very specific thing: not understanding the function of the nut graf. I can’t count the number of times I’ve included a note to a writer pointing to a specific part of the opening section and saying, “hey, don’t forget to put a nut graf somewhere around here.” Then on the second draft, they’ll typically try to retell the entire story in that nut graf. It doesn’t need to be that detailed! It just needs to show the stakes of the story—the So What—and tease some of the stuff that will be revealed later on.

Humberto: How should writers handle queries editors leave for them in the comments?

Brooke: If it is a question with a small, easy fix, I’d prefer for the writer to just make the edit in the draft. If the answer is complicated, or if my question just doesn’t make sense (hey, it happens) then I’d rather have additional context in a comment (and perhaps even a conversation on the phone).

Zoraida: Usually, I expect the writer to answer the questions in the draft or add some comment or background that [explains their changes].

Humberto: If a story goes to additional editors, such as a top editor, how should writers respond if one editor’s changes conflict with those of another?

Brendan: This is a tough one. Your editor should be standing as a line of defense between the top editor and you. If a story has already been through a lot and it seems like the top editor is pulling things in a different direction, you may have to talk with your editor about how crucial it is to make further amendments. See how you can address the top editor’s requests in a way that doesn’t create a lot of extra work.

Alan: The bad news is, the writer doesn’t have much control or leverage in such situations. The good news is, such situations are rare. Most often it happens with a younger editor who might be new on the job or still learning the ropes. Sometimes it happens because your story is so good and important that it catches the eye of the editor(s) above yours, and now they want to weigh in too. In any case, all you can do is weather it; it can feel like trying to steer between a whirlpool and the rocky shore, but try to be helpful and creative in finding solutions.

Zoraida: We have a different sort of top editing at SciDev.Net. We have independent editions for Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, Pacific, and global, and for different languages (English, Spanish, French, and Arabic). And sometimes we have to translate and adapt some stories to a particular audience. The editors of each desk are free to make the adjustments they feel are relevant for their regions, including additional reporting with their own sources and data. In the few cases where we editors have some disagreement, we exchange views, and we ask the author [before we] make drastic changes to the original story.

Humberto: What if a writer disagrees with an editor’s revisions? Is there room for them to push back, and how should they do that?

Hillary: It’s really not advisable to take issue with every single edit. That said, editors can certainly make bad choices. If you feel like the editor is introducing an error into the story, by all means say so and stand your ground. But do it respectfully.

Always be polite. It’s important to be professional and not emotional. Take some time and put yourself in the editor’s position. What are they really asking for? Maybe what you’ve written and what they are asking for aren’t as far apart as it initially seems.

Brendan: As a writer, I remember pulling at my hair, saying, “This editor just doesn’t get it.” They’d rewrite text as they understood it, and it was suddenly all wrong. It took me a while to realize that that was the point. If your editor—who I will, perhaps generously, assume is a smart, engaged reader—is misunderstanding something, then others will too. You should be able to trust that a revision or edit is there for a reason. The edit itself might be wrong, but that doesn’t mean you can put it back to the way it was. Something there was triggering misunderstanding.

Alan: The editing process is so much more enlightening, productive, and rewarding when both the editor and the writer think of it as a conversation. Really, most editors are more interested in the back-and-forth with the writer and knowing that the writer gets the gist of the edit, than in seeing the writer implement every single edit Exactly as Passed Down from Above. A seasoned writer might take only 30–50% of my edits exactly, and another 30% approximately, and another 20% not at all. That actually reassures me, because it tells me that the writer is thinking about what I’m going for—whether it’s syntax or structure or pacing—but also looking for solutions of their own.

If things are confusing, pick up the phone and talk it through—email or texting takes too long, and it’s too easy for fine points to get lost. One writer I worked with regularly would get super-defensive after an initial edit and write me back a prickly email all about how totally wrong my edits were and how they weren’t going to take any of them. Which, OK, no editor is perfect, and a good editor should be open to constructive feedback. But always remember to keep it human between you—and that’s most easily done in real-time conversation.

Humberto Basilio is a Mexican freelance science writer and a TON early-career fellow sponsored by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. He has written for Eos, SciDev.Net, World Wildlife Magazine, and other publications. He is a member of the Mexican Network of Science Journalists and the Oxford Climate Journalism Network. Follow him on Twitter @HumbertoBasilio.